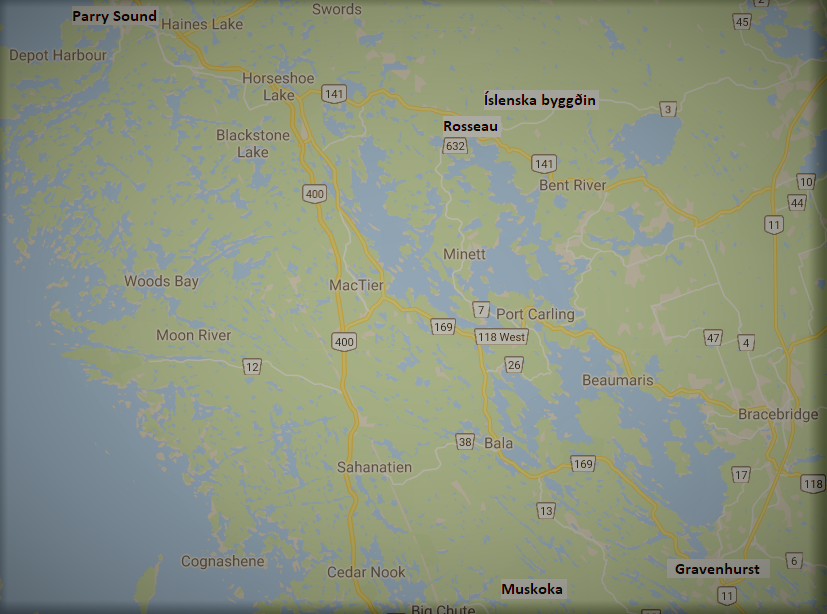

The Muskoka area is in red.

Muskoka is a province in Ontario, Canada that has been inhabited by Aboriginal people for centuries. The district was forested with countless large and small lakes. A truly ideal area for Aboriginal peoples who lived almost exclusively on hunting. The name is derived from the name of one of the chiefs of the Ojibwa nation, whose name was Mesqua Ukie. Soon after Canada came into existence as a provincial nation in 1867, the government began to consider the issue of immigration and primarily the lack of it. At that time, the United States controlled almost all of the southern part of North America as well as Alaska. There was a heavy stream of immigrants from all over the world, especially from Europe. To tempt immigrants, special immigration laws were enacted and provisions for free lands and settlements were introduced in 1868. The Ontario provincial government took advantage of this and tried to direct immigrants into the Muskoka region. A settler was given free land as long as he cleared 15 acres, about 6.1 hectares, of the land and built a 30 square meter (323 square feet) house on it. It was mainly British and German immigrants who paid attention to this and settled in Muskoka before 1870. But the land itself turned out to be unfit for farming, it was hard enough to clear 15 acres, not only of trees, bushes and rooting, but there were boulders hidden in many places that were almost impossible to get rid of. Settlement in the traditional sense where farming and raising livestock was to be practiced did not work out and gradually people gave up and turned to logging. Around 1870 there were no railways or roads, the only means of transport were the lakes and rivers. Steamships and boats made logging a profitable industry because it was easy to get a price for logs. Demand was high in cities and towns, and the laying of railroads westward to the Canadian prairies was beginning. The plans of the authorities for a large-scale settlement in Muskoka largely failed, and it is therefore strange that Canadian officials directed Icelandic immigrants to Muskoka in 1873. In order to get immigrants to settle in Canada, the government negotiated with British shipping companies to commit to write up a document for those who were undecided where to settle in the west to agree that they were going to settle in Canada. Icelandic travelers to the west were to learn this.

The Icelanders are coming: Páll Þorláksson, who went west in 1872 and settled in Wisconsin, became a sort of agent for his countrymen who wanted to settle in the United States. He received news in the spring of 1873 that a large group was expected from Iceland this year, and he was asked to assist them to the best of his ability. He was of the opinion that his countrymen had to adopt new ways of working in agriculture in the West and that the best way was to learn from the locals. The group that set off was less than 200 people, some had decided to settle in Ontario, Canada, while others headed south to Wisconsin, USA. Páll received the group in Quebec in late August and then got into some trouble with Canadian officials who said the whole group had decided to settle in Canada. Páll managed to show them that the passports of those who went south with him to Wisconsin were valid for Milwaukee, having been paid for in Akureyri. Together, all travelers boarded a train that took the group to Toronto. Those who planned to settle in Muskoka remained there, while the others continued with Páll to Wisconsin. The people who remained were given housing and food for three days, but then everyone was herded onto a train that took the group as far north as the track reached. Then everyone was placed on horse-drawn carriages that took the group to the village of Gravenhurst. The group stayed there for one night, but the next day the people were taken by steamboat across the lake to the village of Rosseau.

The map shows Muskoka County. The town of Gravenhurst is the southernmost part of the county, while the Icelandic settlement is in the northern part.

Searching for land: The Icelanders quickly learned that all the land near the village of Rosseau was reserved, so they had no choice but to explore areas further from the village. One such area was about 25 km from Rosseau and Ólafur Ólafsson, Friðjón Friðriksson and Þorlákur Pétursson offered to explore it. They returned after a three-day expedition without finding an area that they thought was suitable for Icelanders. It must be considered probable that they looked for good meadows and grasslands where they could graze, their knowledge of arable farming was not great. Namely, it came to light that not many years had passed after that until Norwegian, Swedish and Danish settlers had occupied all the lands there and were engaged in prosperous farming. The government agent did not give up and pointed to another area much closer to the village, up the Rosseau River. The area in question was in the Cardwell district and the Icelandic settlement there was given the same name and was called the Icelandic settlement in Cardwell. People were still called for an expedition, and Baldvin Helgason, Davíð Davíðsson, Anton Kristjánsson and Jón Hjálmarsson volunteered for this one. They were accompanied by a Canadian guide, which was considered a great advantage because the expedition members had to go through heavy forest. When they arrived in the area, they liked the land because in many places there were very good meadows, which were actually not so good because the frequent floods, spring and autumn, made it difficult for the farmers. But if the government kept its promise that a road would be built from Rosseau, through Cardwell district to the north, then there could be a thriving community here. The expeditioners returned to Rosseau with the news, and there was now some anticipation in the group while waiting for an answer. It came and the road construction was approved. This caused some to settle in Cardwell, but others did not commit themselves to it because of poverty. It was quite late in September, but the weather was still good, so two settlers, Baldvin Helgason and Davíð Davíðsson, moved out to the settlement, as together they had bought 200 acres with a log cabin from a local man. The Canadian was tired of the hustle and wanted to go west to the plains where the country was more desolate. Baldvin and Davíð bought a few cattle which they brought out to their land with great difficulty. They could make some hay before winter came. Others in Rosseau found work logging, poorly paid and difficult. Gradually, the number of people in the group in Rosseau decreased, some decided to try their luck in Wisconsin and went there, others tried their hand in nearby towns such as Parry Sound. Those who were determined were waiting for funding from the government so that road construction could begin.

Logging in Muskoka in 1873

Settlement: Baldvin Helgason and Davíð Davíðsson, the first landowners in the settlement, brought their families to Rosseau and the women and children, a total of nine together, went on foot over meadows and through the forest, “but in most places in the forest there were few obstacles because no bushes grew there and no vegetation managed to take root between the giant trees, which stood so closely together that no sunbeam could penetrate through their great crowns down to the soil, to warm it with its vitality.” (SÍV2 p. 202-3). They moved farm supplies by boat up the river as far as they could, but in many places, they had to drag both farm supplies and boats ashore due to rapids and waterfalls. It was cramped in the house during the winter, where seven children and four adults lived. However, these were not the only Icelanders in the settlement that winter, because Jakob Líndal and Bjarni Snæbjörnsson, two single men from Húnavatnssýsla built a cabin there and lived in it over the winter. During the winter, men worked on the road construction, the four men in the settlement cut down the forest to the south to meet the farmers who were working to the south. This work was too much for many people, and those who had not established land in the settlement lost interest. They felt they had little to show in spite of their hard work, and when news came from other places, men from Rosseau left. When the winter was far gone, only the half-brothers Anton Kristjánsson and Brynjólfur Jónsson from Arnarvatn and Flóvent Jónsson from Skriduland remained in the town. Others who chose to continue began working on their lands in the settlement, cutting down forests and clearing the land. Þorsteinn Þ. Þorsteinsson writes a description of the land and says: “The area where the Icelanders had come to was flat with small hills. No mountain was visible, but the country was covered with a thick forest, from which one could not see hardly up to the bright sky, except where there were clearings in the moist land, with tall grass, which often reached one’s hand. Icelanders had determined that they would be prosperous and proud, because in these lands the settler could make hay for his cow, while nothing was grown on the land, even though they did not have a desirable price in the long run, because the land was usually too rough for arable farming.” (SÍV2 p. .205-6). In the spring (1874), Sigtryggur Jónasson came to visit and went to many places where his countrymen had settled. He told people that he was looking for areas for a large group that would be expected from Iceland in the second part of the summer. Nowhere did he find a suitable area there and looked elsewhere. However, he promised to be in touch regarding the formation of a new, Icelandic settlement in Ontario when it was decided where it would be. The group that Sigtryggur was expecting came to Ontario in the late summer and he took the group to Kinmount, but that option was no better than the Cardwell district in Muskoka. That story is told elsewhere. Two individuals from Sigtrygg’s group separated from that group and went to Cardell district. These were Bæring Hallgrímsson, brother of Þorsteinn in Cardwell and Árni Jónsson, Baldvin Helgason’s sister’s son. He actually didn’t stay long in the west, because after he had lived with Baldvin for three years, he moved back to Iceland.

Kirkjan í Cardwell hreepi var þarna reist árið 1896 Mynd JÞ

Society: The Icelanders who settled in the settlement set out to build an Icelandic society, and since the Icelandic countryside was at the forefront of most people’s minds there in the Cardwell district, society was based entirely on customs and habits from home. Poet Helga Baldvinsdóttir was 14 years old when she went west with her parents, Baldvin Helgason and Soffía Jósafatsdóttir, she recalled the early years in the Icelandic settlement in Muskoka in an essay she wrote in 1940 and ÞÞÞ uses in her account in SÍV2 about the first Icelandic settlement in Canada. Helga writes: “I have often seen it described in books and newspapers, how the groups from home had a difficult time in the first burst after they came west. Most of them, however, usually had some friends to meet, who had come before, except for us, the first group, who went to Canada. It is impossible to describe how many and great difficulties met us in the first stage, and how infinitely grateful we would have been, if someone had been able to guide us.” Helga’s father became a sort of leader of the people in the beginning. He named his land Baldurshaga and encouraged everyone to choose Icelandic town names for theirs. Davíð Davíðsson called his town Lund, Jakob Líndal lived in Fagrahvamm, Bjarni Sveinbjörnsson was a farmer in Bjarnastaðir, Þorsteinn Hallgrímsson in Laufás and Brynjólfur Jónsson in Hlíð as examples. People soon realized that after the first years that the Icelandic settlement in Cardwell district would never be large, the formation of a congregation was discussed little or not at all, but Baldvin Helgason took on general pastoral work, baptizing children and eulogizing the dead. Then he took care of house readings and hymn singing at Baldurshaga on Sundays, where everyone who could arrived from the countryside as well as other Icelanders who lived not far away. It may be that his stay at Melstað in Hrútafjörður with priest Ólaf Pálsson benefited him in these works. Icelanders enjoyed the fact that people of different origins settled nearby, including an Irish man with his wife and children near Baldurshaga who taught Icelanders a lot. Soffía, Baldvin’s wife learned how to plant a vegetable garden, cutting up potatoes for sowing and extracting bark from trees that could be boiled and turned into sugar or syrup. Then Helga, Baldvin’s daughter, learned from the Irish housewife to weave straw hats from straws of wheat and oats, which were light and good protection in the heat of the sun and against the biting wolf when dusk came. Helga also learned how to make soap from ash and leftover fat. With this knowledge, Helga went west with her parents to N. Dakota in 1880, all the way from the Cardwell district. Her brother, Ásgeir, was the only one who returned to Muskoka from N. Dakota, but it must have been in 1886. He soon saw that much could be improved and attended to, such as permission to run a post office that should be called Hekla. It was approved with one serious change, the name Hekla was spelled with two k’s, and despite many protests and requests for a fix, it was never fixed. That explains the name Hekkla, which the Icelandic settlement is now commonly called!

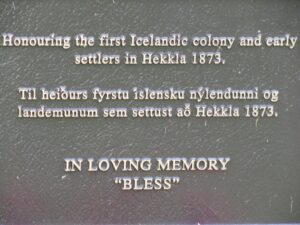

The memorial in the cemetery in the Icelandic settlement. Photo: JÞ