Jón Jónsson from Sleðbrjót took on the task for Ólafur S. Þorgeirsson to write an episode about the Icelandic settlement at Lake Manitoba. The first episode appeared in Ólafur’s Almanak in 1910. Here Jón says about the Swan Lake Settlement (Álftavatnsbyggð): “The events that led to the settlement beginning in these villages were the following: In the years 1881-86, the number of Icelanders in Winnipeg increased greatly. But the city was still developing, there was not sufficient employment for the many people who fled there from all over the country. The shortage of employment became most noticeable during the winter, as few were so well-off that they could sit idle for another semester. There were therefore many Icelanders in Winnipeg who did not think their future prospects were bright there in the city, and therefore began to seriously consider whether it would be a more promising direction to study land and engage in farming. It was often a topic of discussion at entertainment gatherings and other gatherings, where it would be most appropriate to establish an Icelandic colony, because the general prevailing thought among Icelanders was that it would be most appropriate for as many people as possible to try to stay together, be isolated, and if possible, gain wealth and prestige as a separate ethnic group. In this spring 1886, the federal government chose 2 Icelanders to explore the country and choose a colonial area for Icelanders. It chose Freeman B. Anderson, who is often mentioned in episodes of Winnipeg-Íslendingar (Almanak and Saga Ísl. Í Vesturheimi 4), and Björn S. Líndal, who now lives in the Shoal Lake Settlement (Grunnavatns-bygð). They first began their journey inland to the west, to Moose Mountain and the Qu’Appelle Valley; was also accompanied by Stefán Gunnarsson from Winnipeg and a local guide, proposed by the board. These explorers did not like the country in the west, and when they returned to Winnipeg, they set off northwest of Winnipeg to explore the land between Lake Manitoba and Shoal Lake, because at that time the Hudson’s Bay Association had begun to lay the foundations for a railway from Winnipeg west between the aforesaid lakes.”

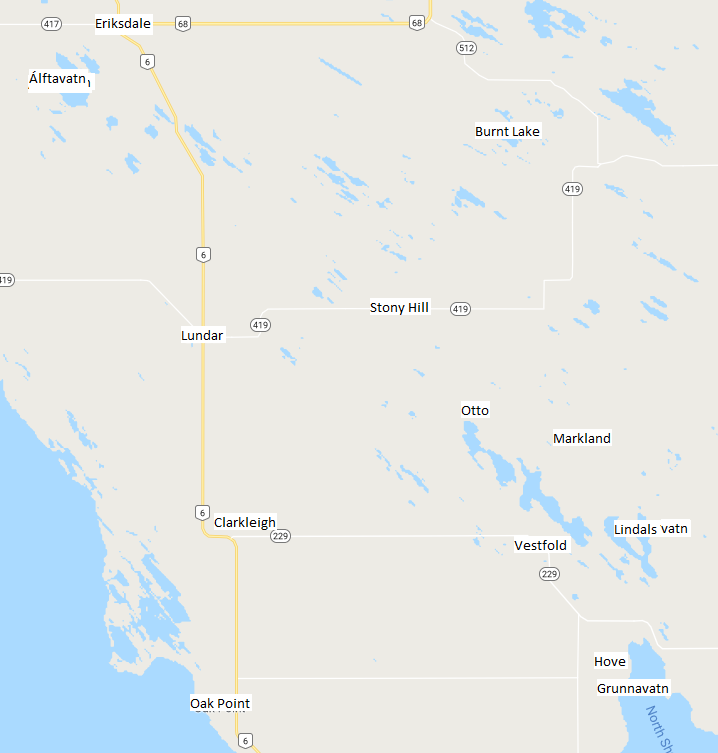

Eastern Lake Manitoba:

“They were accompanied by an English farmer, for it was rather difficult to travel there, as there were no roads but just the paths of the hunters. The whole country was then dry in this area, and B. Líndal has told those who write this that he has never seen a more promising land than when he came into this area. The grass was unusually tall and fell in waves, and the land was suitable for haymaking and cultivation. All of the aforementioned areas they surveyed were then largely uninhabited, and it was their unanimous opinion that the latter was the most promising colonial area. Björn said that these trips were the most enjoyable. Freeman had pursued this work with his usual fiery interest. He had always had a small hand spade (priest’s spade) with him to inspect the soil; said he had often quarreled with Freeman and his countrymen, over the soil and its advantages, and that Freeman had often jumped like a pendulum shot out of the chariot with the priest’s spade in the air and started to examine the soil, and it had often turned out that he had a better understanding than the other Icelanders. Many of those who wanted to study land therefore decided to move out there by the proposed railway, because the inspectors considered this land to be particularly suitable for animal husbandry, and the Icelanders, most of whom had practiced animal husbandry at home, thought it would be a good idea to live there and raise animals, and it would be profitable, when the area was so close to Winnipeg, which was already considered to be the main market in the Northwest (this was the area northwest of Manitoba), and it would be less costly to bring produce to market if a railway were built along the middle of the settlement. Icelanders were also encouraged to explore these areas, as fishing was said to be good in the lakes, especially in Lake Manitoba. They well thought that it would be a great boon to them in the early years of farming, to get fish for a living, while there were few profits, and in time the fish would be able to become a commodity, when the settlers made so much money that they could afford to buy larger fishing equipment, because many of those who planned to settle there, and were used to fishing from home in Iceland. – These were now the motivations for the settlement of Icelanders east of Lake Manitoba: the hope of large-scale animal husbandry over time, and agriculture when materials and circumstances allowed, and the hope, a future that was then considered certain, of economical and easy transportation to the main market of Northwest Iceland.”

It is worth pausing to consider only these expectations of explorers. It is clear that they know well what they are looking for because the emphasis is on livestock farming and fishing. Agriculture is not high on the list of expectations, as it is clear that almost everywhere in the Interlake area, the soil is unsuitable for grain cultivation. It did not take many years before many settlers had started farming in several areas and soon people learned about the lake, realized the migration of fish species and how best to fish. Men like Helgi Einarsson, saw the opportunities and made good use of them. (See section on fishing in Lake Manitoba: Atvinna/ Manitobavatn).

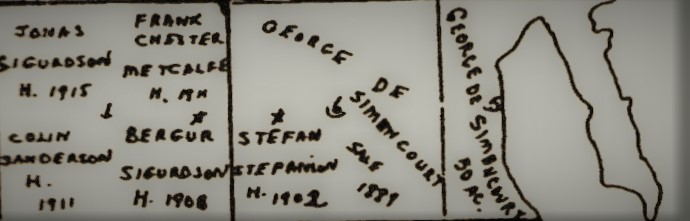

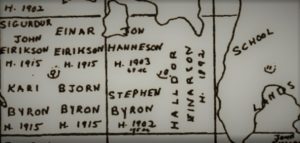

The drawing shows the lands of Jónas Sigurðsson (1915), Bergur Sigurðsson (1908) and Stefán Stefánsson (1901). The “year” show the years of settlement. Next to Shoal Lake (Grunnavatn), a man of another nationality has grazed 50 acres.

The size of the settlement: The map above shows the Lake Lindal, named after Björn Sæmundsson Líndal who settled there. Þórður Kristján Daníelsson and Ísleifur Guðjónsson settled on the east bank of the lake and their lands are the easternmost in the colony. Shoal Lake is south, but the southernmost lands of Icelanders in the Lundar Settlement were the lands of Bergur Sigurðsson and Stefán Stefánsson. (See map next to it) The map then shows Swan Lake (Álftavatn) north of the settlement, but at its southern end was the northernmost settlement of Icelanders. (See chart below)

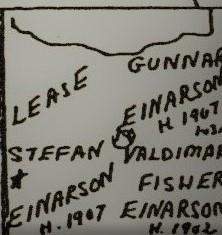

The map shows the lands of the fathers Gunnar Einarsson (1907) and his son Valdimar Fischer (1902). Stefán Einarsson settled there in 1907.

North (top) on the map is Eriksdale. Ólafur Hallsson from Iceland came there in 1910 and built the first residential building there. He ran a shop there and was active in shaping the community around the village. From Eriksdale south to Oak Point are 44 km (27 miles). From the lake through Lundar to the eastern border of the settlement is 30 km (18.6 miles). Burnt Lake is significant in the history of the settlement, as a few pioneers went there before 1890. There they experienced cold winters and their village was sometimes called Siberia. All disappeared from there after heavy flooding and rainstorms in 1890. Most then went south to Markland and formed the communities of Markland, Otto and Vestfold. The school map at the bottom of this page shows the communities because the schools were built in them.

The name Lundar comes from the fact that Hinrik Jónsson took over the post office in a new settlement on the east side of Lake Manitoba. He married Oddný Ásgeirsdóttir who was from Lundir in Stafholtstungar in Mýrasýsla. He applied to the Winnipeg Post Office, requesting that his post office be named Lundir. In this office, new post offices were named and located in the many settlements of Manitoba. Hinrik received a permit for an open post office and it was to be called Lundar. The name had been misspelled.

Churches and congregations:

When a small number of settlers began settling in the same area at the same time, daily life for the first few months turned into setting up a hut for the family and making it tolerable. Next, animals were taken care of if they were possessed, otherwise people began to clear the land, clean and prepare for breeding. Hay was needed for the animals, so they were driven to harvest it before winter set in. The next building after the small house was, of course, a cowshed and barn. Naturally, there were few visits during this project, but when autumn came and more time was given, people began to think about the neighbors. But often someone took the initiative, made an effort to visit the nearest settlers and hear the news from them. During these first visits, the people decided to meet together in a certain town on a certain day to consider the common needs of the inhabitants. In the autumn of 1891, a newsletter was published from the Shoal Lake Settlement (Grunnavatnsbyggð) stating: “At a meeting held at Jacobs Crawford’s home in the summer of 1891, it was agreed to hold house readings in 5 homes alternately, where housing was best, and to spend one hour educating the youth.” The people in the village do this until the turn of the century. These meetings were both beneficial and entertaining. House readings were always read and hymns sung, but then coffee was served and farmers and their wives were given the opportunity to discuss issues, and children and teenagers were also given time to play. At such meetings, people formed very strong friendships, young and old working together to form a small community that later became part of a larger one. The struggle for survival was fierce, everyone struggled with similar problems and lived with similar circumstances. Two things were of great importance to the settlers: to make sure that everyone had enough, and in spiritual matters, people wanted to hear the word of God and educate the youth. These small communities of humans and animals often did not hear Mass sung for weeks and months, but the word of God was what people wanted to hear. If there was a death in the community, it happened that the deceased was carried to the grave without a priest, e.g. were examples of this in Markland, Nova Scotia during the first years of the settlement of Icelanders there in the east. During the last decade of the 19th century, it was customary for people to report on communities’ affairs, and newsletters were frequent on the pages of Heimskringla and Lögberg, which were published in Winnipeg. There was also an Icelandic church association that did its best to send priests or theology students to Icelandic settlements. Thus it was Ingvar Búason, who was the first candidate in a seminary to visit the Shoal Lake Settlement and sing Mass. He did so in the summer of 1895 and had walked all the way from Winnipeg. And at the turn of the century, priests visited the settlement occasionally.

Unitarians: At the turn of the century, floods in Lake Winnipeg swept away humans and animals from various areas in New Iceland, such as in Mikley. These people searched to the west on the plain in the Interlake district and some settled in the Shoal Lake Settlement. Some of the newcomers had joined the religious teachings of the Unitarians and no doubt played a part in the decision of Reverend Albert Kristjánsson to visit the young settlements. He was the first priest to officiate there regularly and reliable parishoners attended his Mass and no doubt some older settlers in the village who perhaps did not care where the good came from! His good work led to the establishment of the first congregation in the settlement on September 12, 1909. It was named Ljósvaki. As usual, a board was elected and the following main positions were filled: Pétur Bjarnason, president, Steinþór Vigfússon secretary and Einar Johnson treasurer. Gradually, this congregation grew, and in 1913, there were 63 registered members of the congregation. The same year it was decided to build a church and it was consecrated and put into use in 1915. Ljótunn Guðmundsdóttir wrote in her time in the anniversary book of the Lundar Settlement (SÁG) and said: “It helped a lot that Reverend Albert served the congregation free of charge during that time, he was himself farming in the east of the settlement. Reverend Albert Kristjánsson was an excellent speaker and a good leader in more areas than the church. He was a good director and actor, and loved to sing and was always ready to take part in the social life of the village.”

Lutheran Congregation: Around 1906, it became clear that a number of colonists were seeking support from the Lutheran Church for clergy in the area, and they responded well. From then on, theologians regularly came to the village and preached sermons, especially in the summer. Services were held at home or at some school. It was in 1913 that a congregation was formed, and Rev. Carl Olson played a major role. The members of the congregation responded well with a joint effort, they built a church west of Otto and it was considered a great achievement because they succeeded without the congregation going into debt. They volunteered all their time and worked on the material for the building themselves.

Reading Societies:

Ljótunn Guðmundsdóttir from Borgarfjörður lived all her life in the Lundar Settlement and made a contribution when requesting material for the Lundar Settlement’s anniversary book. The next sentences are hers: “It is mentioned in a newsletter from Árni Freeman to Heimskringla that the reading society “Mentahvöt” was founded in Árni M. Freeman’s house on February 13, 1889. Eight members joined the society at the first meeting. Jón Jónatanson was the pioneer in founding the society, and he was the first librarian. Initially, the annual fee was $1, later it was reduced to 75 cents. In that year, the first meeting was held in the village to which admission was sold, for the benefit of the reading society. It was a raffle and revenue was $17.65. It wasa rule after that, to hold one meeting a year, to support the club, until the First World War broke out in 1914. That meeting was usually well done. The society was very popular among the locals, and acquired a number of excellent books, as there were well-qualified people who bought the books for many years, such as Björn Thorsteinson, who was librarian for many years, and Hjálm Danielson, who was for a long time the secretary and treasurer of the society, and various others. They showed a unique taste in the selection of the books, some of the books were bought from Iceland, but most of them were bought by Halldór Bardal in Winnipeg, who at that time had a large bookstore. Around 1911, the books were in 4 locations around the village, for the convenience of members; they were then shared at certain times. There were about 300 books in the society, but later the number became about 1,ooo. The reading society “Morgunstjarna” was founded on Hove P.O., around 1907. The founders were Andrés Skagfeld, Sigurður Eyjólfson and Jón Jónsson. The annual fee was $1. The society flourished for many years, acquiring excellent books. Vigfús Þórðarson was for the longest time a librarian. For a time, the books were with Sigurður Eyjólfsson, but were transferred back to Vigfús. He was a librarian until 1926 when he moved to Oak Point. At that time, many members and two founders moved from Hove. On the other hand, the number of members increased in Vestfold, and the books moved there when Vígfús Þórðarson moved away. The society operated for a few years after that, but it was decided among the members that one reading society was sufficient for the needs of the town on both sides of the lake, so the reading society “Morgunstjarna” decided to merge with the reading society “Mentahvöt” and the societies’ libraries were merged. After that, Vestfold residents had a branch of the society library, which was rotated at certain times. Morgunstjarna had about 300 books.”

Post Office:

Magnús Kristjánsson’s home in Otto in the Lundar Settlement. He ran a post office and a small shop where and was often a frequent visitor. It happened that those who had traveled a long way accepted accommodation. Photo: WtW

”The first post office in the young Shoal Lake Settlement was founded on March 1, 1894, and was named Otto. Nikulás Snædal was the first postmaster. But 5 years later Magnús Kristjánsson took over that job, and he worked as a postmaster at Otto for 31 years, or until he moved to Lundar in 1930. The following year, 1895, a post office was established called “Vestfold” on the south side of Shoal Lake. Árni Freeman was postmaster there, and the Third Post Office was also established this year, at the eastern end of the village and on the north side of the lake and was named Markland. Björn Lindal was postmaster there from the time it was founded until he built an estate, and moved away, around 1920. Mail delivery was difficult in those years, poor roads and often very heavy snow in the winter. The Markland mail had to be picked up at Loch Manor, 18 miles. Björn Thorsteinson carried the mail for the first 8 years, sometimes walking, sometimes on horseback or driving at his best. When it was snowing a lot in the winter, he wore snowshoes. After the turn of the century, there was a large influx of people from New Iceland into the settlement. These people had to leave their homes due to floods, and two new post offices were formed, Hove and Stony Hill. Jón Jónsson was the first postmaster at Hove, and Guðmundur Jónsson at Stony Hill. The atmosphere was often hospitable at the post offices, not the least in Otto, Markland and Stony Hill, because in all these places there were shops, people gathered at post offices, not only to pick up the mail, but to buy their necessities, and talk to their neighbors about the day and the road. The postmasters’ wives were busy serving coffee in those days, but they did not regret it, because the Icelanders’ hospitality is in their blood. “

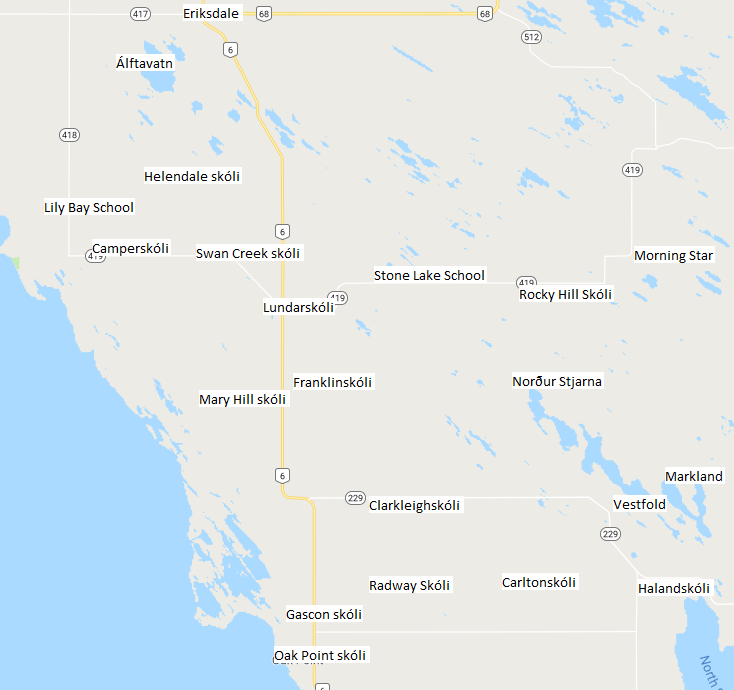

Schools:

From the very first years of Siberia, settlers began to collect materials for school construction, and everyone saw the need for a school to operate as soon as possible. (See Education in Manitoba / Manitoba) did so much damage to people’s estates that people had to move away, some settled on Shoal Lake (Grunnavatn), and gradually everyone moved there and Siberia lay abandoned. The first school built in the Shoal Lake Settlement was Vestfold School, 1894. – The number of students was 11 in the first year, and the first teacher was an Icelandic girl, Ingiríður Johnson, later Mrs. Dr. B. B. Jónsson. Markland School District was established on January 1, 1895. In that year, the school was taught for 44 days, and the first teacher was J. J. Bíldfell. The next teacher at that school was Björg Thorkelson (daughter of Jón Jónatansson and Guðrún Sveinungadóttir), the first Icelander to graduate from a teacher training college in Canada. In 1903, two school districts were established, Norðurstjarni and Háland. The first teacher at Háland School was Emily Baldwinson (later Mrs. J. Pálsson), and the first teacher at Norðurstjörna School was Steinunn Stefánsson (Mrs. Sommerville). Many good Icelandic teachers taught in these schools over the years, and it was to the great benefit of the students. At the end of each school year, a gathering was held where the children engaged in games, readings, and sang. This helped build confidence. Teachers like Fred Olson, who taught at Markland in the summer of 1900, will be unforgettable to his students, not least for the boys; he taught them to play football and various other games, with more art than ever before. It was customary around and after the turn of the century for 8 to 10 schools to have picnics, where the schools competed with each other in various sports, and there was also a parade in which the schools took part, each under its own flag. This aroused competition among the children, and they were very interested in their school winning as many prizes as possible, unfortunately outdoor activities in this form have stopped. ”

The first school in the Swan Lake Settlement (Álftavatnsbyggð) was Franklinskóli which was founded in 1889. A building was built a few kilometers southeast of Lundar. This school was moved to Lundar in 1911 and classes were taught there until a new building was completed in 1914. Swan Creek School began operations in 1892 and is located about six miles northwest of Lundar.

The map shows the schools that were operated in the Lundar Settlement from 1885. Most Icelandic children were in schools closest to Lundar, such as Franklin, Mary Hill, Swan Creek and Stone Lake. It can be said that the schools Morning Star, Rocky Hill, Norður Stjarna, Markland, Vestfold and Haland had been mostly Icelandic for at one point. As the years passed and the number of children decreased in some areas, schools were closed, and children transported between settlements. Over the years, settlements mixed considerably, land bought and sold, nationality gradually became less important.

School: Lily Bay school:

The Lily Bay School was built in 1911. Photo by WtW

One of the first school districts in the Swan Lake Settlement is Lily Bay, founded in 1885. The inhabitants of the district were mostly British and they joined forces with other settlers and built a log house that was used as a school building until 1911, when another, larger school was built. Icelanders were few in number there by Lily Bay and few Icelandic children attended it. Only one Icelandic teacher, Tom Breckman, is known.

Franklin School was built in 1903 and moved to Lundar in 1911. Photo WtW.

The first school in the Swan Lake Settlement that can be considered Icelandic was Franklinskóli, which was founded in 1889. At a meeting in the countryside on January 6, 1890, it was agreed to start construction on a school building. The school was built a few kilometers southeast of Lundar. At Þorláksmessa in 1903, a meeting was held on school matters and it was agreed that it was necessary to build a new and larger school building. That school was moved to Lundar in 1911 and classes were taught in it until a new building was completed in 1914. Among the teachers in the first years were Björg Jónsdóttir, Ingvar Búason and Árni Anderson. Jón Sigfússon was the school’s first trustee and held that position until 1903.

Chalton school:

A school district in the southern part of the settlement was called Chalton or (Carlton???) and teaching began there in 1889. A wooden schoolhouse was built and used for many years both for teaching but also for all community meetings as well as entertainment. There were few Icelanders, but the students at this school had a yearly gathering with their Icelandic peers at the school in Havland (Haland?). Icelandic teachers at the school were e.g. Kári Vigfússon and Kris Breckman.

A school district in the southern part of the settlement was called Chalton or (Carlton???) and teaching began there in 1889. A wooden schoolhouse was built and used for many years both for teaching but also for all community meetings as well as entertainment. There were few Icelanders, but the students at this school had a yearly gathering with their Icelandic peers at the school in Havland (Haland?). Icelandic teachers at the school were e.g. Kári Vigfússon and Kris Breckman.

Vestfold school: The school in the Vestfold Settlement was founded on March 19, 1894. The schoolhouse was a log house, built on land that Halldór Einarsson gave to the school district. In 1909 a new school was opened and stood somewhat to the south.

The settlement map shows Halldór Einarsson’s land next to the lake. He settled there in 1902 and so did his neighbor Stefán Björnsson. He changed his last name to Byron but his two sons, Kári and Björn settled in the next section as can be seen.

The old schoolhouse in Vestfold was a log house and was used until 1909. The picture taken in 1900 in front of the building includes Kári Byron. He always lived in the Lundar Settlement, was an entrepreneur and held various positions.

Back: Árni Anderson, teacher. Row in front of him: Stína Johnson, Rúna Johnson, Villi Freeman, Hanni Snidal, Sibba Einarson, Munda Johnson, Helga Einarson, Jóna Johnson, Einar Einarson and Magga Freeman. Foremost are: Jón Ingimundson Johnson, Lína Johnson, Kári Byron, Lóa Snidal, Þórður Snidal, Björg Jóhnson and Einar Johnson

The school vastly changed the lives of the children in the surrounding countryside, because even though many of the parents had mastered some English, Icelandic was usually always spoken in the home. English was taught and the youngest children took time to learn English. The school was open for five months during the summer and as the water was scarce, the children gladly took the opportunity in the heat of the summer and cooled off in the water. The rule was that all students go there once a day. Sports were part of the school’s curriculum every summer and athletic students competed with their peers from nearby schools. The schoolhouse is useful to the countryside for other things as well, e.g. entertainment and dances were held there. Then plays were staged and at Christmas there were concerts that were very popular. Teachers were Icelandic in the first year and Lena Johnson was the first teacher, then Árni Anderson was hired in 1898, Guðný Kristjánsson and B. I. Sigvaldason joined the group. In 1959, the Vestfold School District was incorporated into a new one called the Lakeshore School Division.

Markland school: Björn Sæmundsson Líndal settled in a new Icelandic settlement in Shoal Lake in 1891. A school was built on his land by a lake which later bore his name and is still called Lindals Lake. Björn took care of school matters well because he was the chairman of the school board for 25 years or until he moved out of the village. The school’s first teacher was a young man from Winnipeg, named Jón J. Bildfell. He later became editor of Lögberg, published in Winnipeg. He took over the teaching for two summers, 1895 and 1896, but in 1897 the school was not operational due to lack of funds.

Gamli Marklandsskólinn (The old Markland school) was built in 1895. Björg Jónsdóttir, daughter of Jón Jónatan’s son Þorkelsson and his wife, Guðrún Sveinungadóttir, was the school’s first teacher. She came west in 1883, studied education and was granted a teaching license in 1890 and was the first Icelander in Manitoba to receive such a license. Photo: WtW.

These students were in school in 1907: Front row: Kari Johnson, Ernest Eirikson, Skapti Johnson, Thorsteinn Thorsteinsson, Jonatan Johnson. In the middle: Margaret Thorsteinsson, Emma Sigurdson, Erna Stefansson, teacher, Sigga Erickson, Jana Danielson. At the back are: Arthur Eiriksson, Laufey Lindal, Nybjorg Halldorsson and Jon Jonsson. Photo: WtW.

The school board solved the financial problem and Björg J Thorkelson was hired as a teacher at the school in 1898. During the school’s operation during the summer, the older students at the school often had to drop out of school at some point in the summer when it came to haymaking. As a result, the school operated during the winter and was then presented with a special stove in the living room and lit with charcoal oil lamps. The children were transported on sleighs to and from school in the winter and in horse-drawn carriages in the summer. The teachers at the school always enjoyed the great hospitality of parents who all wanted to prepare their children for the future in a growing society where English was the national language. However, they also explained to the teachers their Icelandic origins and the children, striving to ensure that the Icelandic heritage was honored at school. In particular, they wanted the children to learn to read Icelandic. The school building was used in various ways, where people danced, met, held meetings and performed concerts. This was discontinued when the Markland Hall meetinghouse was built in 1904. The school’s main teachers were Jón J. Bidlfell 1895-1896, Björg Thorkelson 1898-1901, Fred J. Olsen (Friðrik Júlíus Ólafsson) 1901-2, Evelyn Lundy 1903, Mary Kelly 1904 -1906, Jonasina Stefansson 1907-1908, Margrethe Thorlaksson 1909, Rose Magnusson 1910, Bjorgvin Stefansson, Rannveig Thorsteinson, Asta Austman, Rev. Guðmundur Árnason, Thora Stephenson, Jon Runolfson, J. Magnus Bjarnason, H. Bardal, CA Shewfelt, Laura Sigurjonson and Jana G. Gudmundson.

Mary Hill school:

Mary Hill is a large community south of Lundar and a school district was formed there in 1899 and in the same year a school started operating there. Þorvaldur Þorvaldsson from Skagafjörður was the school’s first teacher; he came west when he was 8 years old with his parents and siblings in 1887. His brother Þorbergur took over four years later. Many children and teenagers were in the settlement from the very beginning and the number increased rapidly. For example, when classes began in April 1906, there were 18 students in the school. By the end of May and June of that year, the number of students had risen to 36. The children’s parents took turns hosting the teachers during the first years. As usual, the building was used for various entertainment and meetings. Church services were also held there.

The other main teachers at the school were Freda Harold, Dora Eldon, Miss Henby, Lawrence Johannson, Hallgrimur Jonsson, Emma Johannesson, Lena Johnson, Helga Arnason, Hilda Arnason, Rannveig Thorsteinson, Hilda Erickson, Freda Einarson, Henry Powell, Barney Thordarson, Mary Foster,

Front row: Kristjan Bjarnason, Johann Johnson, Larus Johnson, Einar Eirikson, Oli Olafson, Joe Westman, Bjorn Thorlakson, Arman Magnusson, Bjorgvin Gudmundson, Allan Sigurdson. Next row: Runa Olafson, Steinun Hallson, Thora Bjarnason, Bjorg Gudmundson, Inga Johnson, Helga Johnson, Olof Olafson, Gudny Magnusson, Karitas Breckman, Margret Eirikson. Third row: Sigridur Johnson, John Johnson, Lauga Westman, Johanna Einarson, Ella Johnson, Stina Johnson, Thorbergur Thorvaldson, teacher, Bjorgvin Stefanson, Airikur Sigurdson, Oli Sigurdson, Bjorn Hallson, Jonatan Magnusson, Back: Eyolfur Bjarnason, Gudni Stefansson, Bjarni Nordal, Gudjon Hallson, Jon Johannson, Bj0rn Stefansson, Lena Peturson, Olof Olafson, Inga Bjarnason, Bjorg Thorkelson, Frida Stefansson and Thora Olafson. Photo: WtW Students of the school and Þorbergur Þorvaldsson teacher.

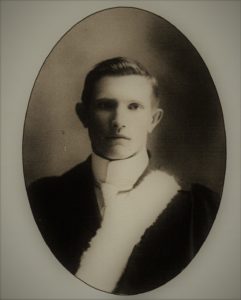

Þorvaldur Þorvaldsson, the first teacher at the Mary Hill school in the Lundar Settlement, was from Skagafjörður.

Alla Brynjolfson, Mr. Burnell, Johannes Eirikson, Rose Racklin, Lauga Phippen, Helga Reykdal, Mildred Hackland, Rosa Johnson, Olaf Sigfusson, Vivian Magnusson, Miss E. Reid, Doreen Breckman, Hiram Clark, Leonre Guerney, Marguerite Laidler, Baldwin Berg and Anne Thorkelson. (The sentence should not be split by the photo.)

The chairmen of the school board were: Skuli Sigfusson, Gudmundur Gudmundson, John Sigurdson, Stefan Olafson, Sigurdur Sigurdson, Einar Borgfjord, Bjorn Austman, Gudni Stefansson, Bjorn Bjornsson, Mundi Sigurdson, Helgi Bjornsson, Bjorgvin Gudmundson, John Johanson, Barney Nordal, John Thorgilson, Albert Einarson, Rannveig Gudmundson, Sveinbjorn Olafson, Arthur Sigfusson, Robert Hallson and Magnus Bjornsson.

Norður Stjarna (North Star): A new school district was approved in the Lundar Settlement on April 3, 1903 which was called Norður Stjarna (North Star). Many Icelanders had to leave their farms in Mikley and settled in this settlement. Construction of a school building began the same year, but it was difficult to complete because the area was quite treeless and lumber had to be picked up from nearby settlements. Franklin E. Sigurdson recalled that his father, Sigfús Sigurdson, had probably driven his horse-drawn wagon all the way to Oak Point. (WtW p. 46) Other settlers had to do the same when building a house. The sawmill was north of the settlement and most people probably went there. The school was spacious, the classroom large but on the upper floor was a dining room. A stove was introduced on the ground floor, but later a basement, a heating room, was buried under part of the house. The school was in the southern part of the district and students were transported to the school in carriages and later a special school bus.

There were different distances between schools in the Lundar Settlement, but that did not change much because efforts were made to hold joint sports tournaments and gatherings. The students’ annual summer festivals were very popular. The students in Norður Stjörna, Vestfold, and Rocky Hill met annually on a field east of the Norður Stjörna school. The day always began with a parade, each school had its own flag and carried by the highest grade students of each school. Some wore school uniforms, but they were not required. At the end of the parade, the students of each school sang their team’s fight song and then a sports tournament began. They competed in various races and football games. Prizes for victory, second place and third were awarded, usually a small amount of money. The ladies society (Kvenfélagið Frækorn) took care of refreshments during these days, but every housewife in the district belonged to this association and it only mattered which school her children went to. A special ice tent was set up on the field and all children, seven years and younger, were given one free ice cream, older children paid a few cents for theirs. Philip Johnson and Sigfus Sigurdson took care of the ice tent.

The main teachers of the school were Steina Stefanson, Th. J. Johennesson, Harvardur Eliasson, Gudmundur O. Thorsteinson, Sigurlin Johnson, Jon Straumfjord, E. Holmquist, Agnar Magnusson, Sigga Peterson, Rev. Hjortur Leo, Johann Magnus Bjarnason, Thorstein O. S. Thorsteinson, Ruth Bardal, Lilja Erlendson, Lottie Olafson, Palina Johnson, Stina Skulason, Felix Sigurdson, Emma Tomasson, Gudmundur Eyjolfson, Chrissie Halldorson, Lillian Olson, Magnusina Jones, Joyce Ford, Dagny Kristenson, Pat McFee, Margaret Proven, Eleanor Westman, Frank Olson, Rosa Johnson, Siggi Sigurdson, Helga Eirikson, Joyce Spring, Sigrun Skulason, Magdeline Gisbrecht, Mara Hunter, Eileen Kaul, Peggy Bjornson, Dennis Einarson and Sigurbjorg (Sibba) Johnson.

As in other Manitoba rural areas, the school building was originally used as a meeting house, dance hall, and theater. In 1919, the school was rebuilt and another classroom opened. It turned out to be somewhat ill-advised because in 1920 the number of students decreased but loans continued on the new building for 20 years.

English version by Thor group.