The area where the two settlements were located stretched from Churchbridge, Saskatchewan in the south some 35 km (21.7 miles) northeast towards Calder. Originally there were two separated settlements, Thingvalla settlement in the south and Lögberg settlement in the north. As the years passed and roads improved, the two amalgamated and were then referred to as Thingvalla-Lögberg settlement. The land in the entire region is slightly rolling with depressions here and there, mostly dry during dry spells but filled during wet years forming sloughs. Poplar trees and willow bushes grew here and there on the higher land and bluffs in the south but larger poplars grew in the north, ideal building material for the early settlers. During the settlement time, around and just after 1900, the open prairie was covered with tall grass. Bison bones scattered here and there were often found, evidence of previous inhabitants. The Icelanders selected such areas first and foremost for as good possibilities for mixed farming, grain and livestock.

Thingvalla settlement: The editor and publisher of the Icelandic newspaper Leifur, Helgi Jónsson in Winnipeg, was instrumental in promoting possible settlements further west of Winnipeg. He was hired as a colonization agent by the Government of Canada. When he learned of plans for railroads out of Winnipeg into the vast Northwest Territories, later to become the provinces of Saskatchewan and Alberta, he saw tremendous possibilities. Knowing that railway stations were required at certain intervals to service the steam engines, small villages would be established where the settlers in the surrounding settlements would obtain necessary supplies. Here were golden opportunities for anyone interested in opening and running a small business. He assumed that the northwest railway would cross through the village of Shellmouth and went ahead and opened a retail store there in 1885. But politics intervened, plans were changed, and the railroad moved several miles south. Helgi reacted quickly, moved to a place called Langenburg, and this time his instinct was correct, the railroad reached Langenburg in 1886.Early that year Helgi had a house built for himself and his wife and a store commercial building where he and a new partner, Bjarni Davíðsson from Dalasýsla, opened a store.

Icelandic settlers: Immigrants now could travel by train to Langenburg and from there the distance out to the settlement was around 25 km (15.5 miles). The first to arrive were Einar Jónsson Suðfjörð (Sudfjord) from Barðastrandarsýsla, Jón Magnússon from Lón in E. Skaftafellssýsla, Björn Ólafsson from Borgarfjarðarsýsla, and Narfi Halldórsson from Árnessýsla. Jón was the first to build a small hut. Helgi Árnason was an early settler and in an article published in the 1918 Almanak, he described the first year: “In the winter of 1886-87 some 23 families had arrived and settled in the colony. Their abodes were understandably small and inconvenient, but that winter men worked hard in the small woods gathering lumber and gradually proper cabins were built. Seven ox teams had been brought to the settlement and in the spring Guðbrandur Narfason from Gullbringusýsla brought in the eighth. All of them were in constant use when weather permitted. The spring of 1887 saw an influx of settlers from England who settled near the Icelandic colony. The Icelanders benefitted from their arrival as they could sell them hay and lumber as well as working for them on the construction of homes. Work on the railway also helped many get established, the Lunenburg railroad was gradually extended westward. The pay may not have been the best but small earnings helped during the hard and demanding work on each settlement”.

School and congregation: In the fall of 1887 discussions on the establishing a school district commenced. The construction of a school building was discussed, all settlers felt that was the most important project for the settlement. As winter approached men worked in the woods, gathering logs and bringing them to the future school ground. The construction began in March, all men in the settlement participating in this voluntary project. Thomas Paulson was in charge. The Railway company offered a $100.00 grant towards the cost which enabled the completion of the building without any borrowing. The school was opened in the summer, Miss Guðný Jónsdóttir was hired as a teacher. Later she married Magnús Paulson who became editor of Lögberg in Winnipeg. A public meeting was called in January of 1888 in the home of Einar Sudfjord, and on the agenda was a congregation for the settlement. The establishing of Thingvalla Congregation was completed at the meeting, some 36 settlers joined the new congregation. Thomas Paulson was elected President of the Church Committee, Árni Jónsson Secretary, and Jón Ögmundsson Treasurer, and Sigurður Jónsson and Kristján Helgason associate members. Sunday School teachers were Mrs. Elín Scheving and Sigurður Jónsson for the south and Guðbjörg Sudfjord and Margaret Jonson for the west. Another meeting was called later that month at which quite a few new members of the congregation signed up. The first Pastor to visit the community was Rev. Jón Bjarnason who arrived late in October of 1888. He preached in the schoolhouse, baptized some 22 children, solemnized 8 marriages, and dedicated the new cemetery. It should be mentioned here that Guðbjörg Sveinsdóttir, wife of Helgi Sigurðsson from Vatnsendi in Eyjafjörður, had passed away on March 1, 1887. A meeting had been called at that time in order to select a site for a cemetery. The meeting attendees agreed to accept the offer made by Narfi Halldórsson, who offered an acre of land, as the location was considered ideal in the center of the colony. Eventually the parish church was built nearby. Guðbjörg was the first person buried there. Einar Sudfjord and his wife lost a child just before the funeral and was the baby was put to rest with Guðbjörg.

Lögberg settlement: This settlement is in the northeast area of the Churchbridge – Calder region. The number of settlers in this part was never high as it was much smaller. Instead of

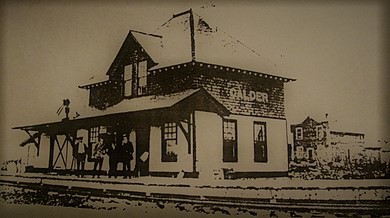

spreading out, the new settlers crowded together as they did not realize how large each farm had to be for mixed farming. This explains why so many left the settlement in a few years. Had a village been established early where Calder now is located, this settlement would have grown northward. But the railway did not go through Calder until 1910, the village and railway station were established a year later. In order to get necessities, settlers had to travel a great distance through the Thingvalla settlement to Churchbridge. A good relationship was soon established between the settlers of the two settlements.

Calder train station in 1916

Icelandic settlers: The first Icelandic settlers arrived in 1890, Gísli Egilsson from Skagafjarðarsýsla and Jóhannes Einarsson who emigrated from Iceland in 1889. Gísli moved north to Winnipeg that year from Hallson, N. Dakota. He had emigrated from Iceland in 1876, settled in New Iceland, but moved to N. Dakota in 1880. Fate brought Gisli and Jóhannes together in Winnipeg where they considered options, as both were looking for a settlement site where they could establish themselves in Canada. Here the experience of Gisli in matters concerning pioneer life, and the enthusiasm of a newly arrived immigrant made a good team. Author Walter Lindal wrote: “They were men of vision – community builders.” From the beginning, both strove to support and help newcomers, encouraging all to work together at making the settlement a success. As the years passed both raised large families. New settlers travelled west by train to Churchbridge and by oxcart to make the 25 km (15.5 miles) from the village to the settlement. The site offered little building material, so the first homes were small sod houses. A story illustrating the size was told for a long time with by the settlers. An eight-year-old boy travelled on the train with his parents and a cow. The father had been to the settlement in the spring, built his hut, and returned to Winnipeg to fetch the family and a cow he had just bought. As they reached the site and the new home was pointed out, the child called out: “Is this for the cow?” A few settlers brought livestock to the site, one was Ólafur Árnason from Árnessýsla who emigrated in 1886 and settled in Lögberg in 1892. He drove the animals quite a distance and used what remained of summer to make hay. He did not have a mower or a rake, so he used a hand scythe to cut enough for his animals to last the winter. He had help with gathering the hay, men brought hand-rakes. The winter that followed was one of the coldest, but Ólafur managed to keep all his animals alive.

Schools and Church: In the northwest part of the region, settlers from Scotland as well as Germany had already settled. Authorities decided to establish a new school district in late 1891. A schoolhouse for the entire region was to be built and a site northwest of Calder was chosen. From the beginning it was obvious that the location was most inconvenient for most Icelanders in the Lögberg settlement as the distance was too great. Another school was therefore built much closer. The Icelandic settlers in both the Thingvalla and Lögberg settlements wanted their churches once congregations had been established. The first church was built in Lögberg settlement, construction began in 1902 and was completed in 1904.The building also served as a community hall for both settlements.

Dry cycle – Exodus: The settlement in Lögberg was complete at by the end of 1891. Most settlers had started farming, and the number of livestock had increased, so water was crucial. Each settler strove to find water on his property; wells were dug, many to no avail. During the normal spring melt sloughs had water that lasted into the summer, but more was needed. The situation worsened and the summer of 1892 was the driest. The settlers had never heard of a periodic dry cycle on the prairie like the one they now faced. Neither experienced farmers nor government authorities understood the situation and could not explain why wells in the Lögberg area gradually dried up. Some settlers tried new locations within the settlement and Canadian authorities sent experts into the region, but nothing worked. In the spring of 1893 the exodus began, most settlers headed east to Manitoba and settled on the western shore of Lake Manitoba. Others headed north and west to areas near Foam Lake and Fishing Lake. More than half of settlers in both settlements left, but those who remained sold some of their animals and struggled on. Their determination was the foundation of an Icelandic community lasting well into the 20th century. It should be noted that both Gisli Egilsson and Jóhannes Einarsson stayed on. (The above on the Lögberg settlement is based on The Saskatchewan Icelanders).

Improvements: When the dry cycle ended late in the 19th century, the prairie slowly returned to its normal condition. Farmers who had remained and struggled through the dry times began to add farmland and gradually began growing grain. They encouraged relatives to come and settle on the improving lands in the Thingvalla- Lögberg Settlements. Likewise, they contacted those who had left and settled elsewhere, encouraging them to consider a return. New settlers arrived in an already established settlement where experienced farmers already lived. They settled on lands already broken, the hard pioneer work had been done by others. During 1900 – 1914 almost 30 new farmers moved into the settlements with their families.

English version by Thor group.