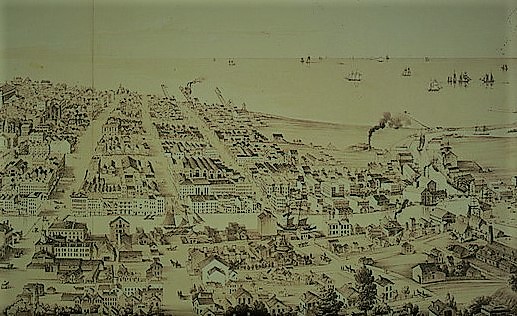

Milwaukee 1870

Sigurjón Sveinsson was born at Syðrafjall in Aðaldal in S. Þingeyjarsýsla. He grew up in his parents’ home, Svein Jónsson and Soffía Skúladóttir, first at Fjalli and then at Garður in the same district. He wrote down a description of his life in the West and Þórstína Sigríður Þorleifsdóttir included a chapter from his manuscript in her book, Saga Íslendinga i Norður Dakota, published in 1926. (JÞ)

Coming West: “It was May 28, 1873, that Sigurjón set sail from Iceland, on an old merchant ship named Hjálmar. There were 11 of us who set sail on the same ship; but that vessel was in such a poor shape so there was less chance that they would ever reach a harbor safe and sound. They ran into wind, strong and great waves in the sea, and were often in doubt as if this would be the end of old Hjálmar. However, they finally landed in Kristianssand in Norway on 5 May. They continued from there and first to Bergen in Norway. But there they took the liner “Haraldur hárfagri” (Harald Fairhair) to New York in the USA. From there they took a passenger train to Milwaukee in the state of Wisconsin. – When they arrived in Milwaukee, they immediately set off to look for work and succeeded in securing various jobs.

Years in Wisconsin and Michigan: That summer, Sigurjón stayed in Milwaukee until fall. When it was harvest time , they got together to find work among the farmers. Sigurjón was among them. the search was in vain, because in most places farmers let their guard dogs loose, driving them away. Perhaps their poor clothing had something to do with it the work clothes that they wore had previously been used for shoveling coal and various other dirty work. In those times, vagabonds went from one corner of the country to another, and lived mostly on begging and various odd jobs; the Icelanders were often considered of such group, and therefore no mercy was given. They often slept outside at night, but they were unaccustomed to the heat, as well as the flies that pested them, so they were badly bitten. Sigurjón worked for four days at a farm not far from Milwaukee, but then returned to the city. In the autumn, the fellow-countrymen still gathered together and now went out into the wilderness to cut trees in the forest. There were 12 of them together, who took up the work of cutting firewood, and they were supposed to get 1 dollar as pay for each firewood load, cut and split. They were unaccustomed to the axe, and one of them had been to kepp on working at sharpening and repairing axes that had been damaged. After the first week, the companions had completed 12 fathoms of firewood in total, but three had been injured during the week. Sigurjón spent four years in various places in the states of Michigan and Wisconsin, either chopping wood in the winter or fishing, and working on boats that traveled across Lake Michigan between the states in the summer. There, Sigurjón experienced the heavy sorrow of seeing his brother Páll drown before his eyes in Lake Michigan. The brothers had arrived together from Iceland and were very close. In the spring of 1877, Sigurjón went out to a farming community. He worked in the summer for farmers, mostly in what was called Clinton Plains, about 60 miles south of Chicago. They were together most of the time that summer, Sigurjón and Benedikt Jóhannesson from Eiríksstaðir in Jökuldalur. They each bought their own team of horses in the fall, and drove them about 400 miles to Shawano County in Wisconsin, because quite a few Icelanders had settled there by then.

From Wisconsin to N. Dakota: The following summer, many of the Icelanders who had settled in Shawano County were thinking of moving to North Dakota, and had reports from there of splendid land opportunities and future prospects. They teamed up for that trip, Sigurjón, Benedikt, Kristinn Kristinnsson, and the Þorlákssons, Haraldur, Björn and Jón. Those who owned land sold their property and bought horses and wagons. They became a caravan of 5 teams of horses, with about 1400 miles to go. Sigurjón says that he has never taken a more pleasant or inexpensive trip in his life. Hospitality and friendliness met them everywhere, it seemed that everyone wanted to do their utmost to comfort those who were on long journeys in those days. One such farmer, Bótólfur Olsen, had settled not far from where the Icelanders had taken their lands, which later became the Hallson settlement.

Indians: A short time after those companions had arrived in North Dakota, a meeting was set up with Bótólfur, the farmer, by the settlers, to discuss and thoroughly discover how much habitable land there would be around the settlement, especially to the south and north. Bótólfur Olsen, Sigurjón Sveinsson, Jón Bergmann and Pálmi Hjálmarsson from Þverárdalau in Húnavatnssýsla, who had just arrived there from New Iceland, were hired for a survey. They had one small carriage for the journey and two small horses to pull it, and one of them was Úlfar, the horse that belonged to Reverend Páll Þorláksson. They had food reserves with them in the wagon and some utensils, but they mostly walked, except when they took turns driving. They went north and there was a lot of wet land and high grass. They had not been gone long when they became aware of a large group of Indians who were staying there on the plain. But as the Indians became aware of the others’ travels, they suddenly gathered their packs and set out to meet the White men. There was a large patch of sedge between them, ending in a point in the distance, a little further away. It seemed to the group that there the Indians would be likely to ambush them as they seemed unfriendly. Farmer Bótólf was familiar with military operations and was happy with the Indians at that time. He went before his companions and said that the only way was to go on and pretend to be undisturbed, because if they stopped, the Indians would immediately ambush them and make a quick mess of them. It was according to his advice that they tied up their horses, then crawled each in their own direction into the sedge. Bótólfur said that it if it should happen that one of them escaped, he could tell about the fate of his companions. It was very wet down there, but they knelt as far into the grass as possible, and did not move around, even though the rain was soaking them. They lay there until night. But as they had no idea of the redskins’ journeys, they dared to gradually stretch themselves out of the tall grass and look out to the point ahead. The Indians were by then out of sight, and the companions praised Providence for a good outcome. They felt they were badly prepared to meet the actions of the warlike Indians. Bótólfur only had a soldier’s gun as a weapon, which he had received recognition for his good performance in the American Civil War. Sigurjón had his pistol, which in those days was common for men to carry with them wherever they went, but Jón and Pálmi had a different weapon than the others, a good folding knife; felt they were comfortable with such weapons, if the redskins had sought them out, which was not uncommon in those times, that they would hunt for the scalps of white men if they got the chance. But when the poor men were satisfied that the Indians had gone their way, they returned to the place where they had left their horses and started again. It seemed to them most likely that the Indians would not have had less of them than they had of them. They had probably thought they were part of the military force that was stationed at Pembina, to make sure that the Indians did not gather into large groups on the plains, where the sparse population of new settlers had settled. Sometimes they were surprised when the soldiers fired their guns when the Indians were near, so that they were terrified.

Settlement: Little happened to them in this journey, other than that they were more likely to find Icelanders to the south, who at that time had occupied lands there. The Þorlákssons chose each a piece of land and made a small settlement, which they called Vík, but later became Mountain. Sigurjón and Benedikt continued further south and had settled further south than any Icelander by then, all the way to the stream that was called Park River, but later became Garðar River. Sigurjón then took land there, but Benedikt shied away from taking land at that time. Sigurjón had a good crop of hay that summer. But when the hay season was over, it was autumn and harvest time had come. Sigurjón hid all his possessions and clothes, except for the ones he was wearing, in one of the haystacks, while he helped in harvesting corn for farmers near Cavalier. It was during one day, when Sigurjón was at his work, than as he looked towards Mountain and his settlement; he saw the whole settlement in a blaze of flames. Terrible prairie fires raged there throughout the southern part of the Icelandic settlement. All of Sigurjón’s possessions and his farm were burned to the ground, so that he had nothing left but what he was wearing. He then took it upon himself during the winter to go north to Winnipeg and there he went to work striking railroad ties for the C.P.R. railway track, which was then being laid on both the east and west sides. When spring came, Sigurjón went back to Dakota. Benedikt was there then. He took land that autumn, attached to Sigurjón’s land. Those companions stayed in Vík for the winter and bought hay bought for their animals, because there the fire had not raged as unhindered as it was further south. Now they set up a partnership for their farms, it was spring. However, it turned out that Benedikt still went out for summer work, but Sigurjón stayed behind. He had a herd of oxen that was his own, and another that Benedikt had. He plowed on both lands with them during the summer but had a man with him who did the other work. They had a cellar dug on the premises with roofing timbers across it. They didn’t think it’s too bad to live like that, because it protects them well from fly bites and bad weather. Rather, the diet was poor and kitchen utensils were scarce. Benedikt had one pot which was used for all cooking, and many of those who have had to live the life of a single settler will be familiar with that tool. The middle and the lid were rolled into the pot, so that bread was baked in it by arranging embers around the pot and lighting a fire. The only food was the loaves of bread baked in the pot and a glass of milk with it, because there was nothing else to be had. But as the summer wore on, more people began to move into the area and the settlement expanded and grew. The fall before, Eiríkur Bergmann had come there on an inspection of the country from the south. – It took time for land to be taken and the settlement to become more populated.

Marriage – Family benefits: In the fall of 1881, Sigurjón married Valgerður Sylvía Þorláksdóttir, daughter of Þorlákur Jónsson from Stóra – Tjörn in Þingeyjarsýsla, and sister of the previously mentioned Þorlákssons. They first set up a farm on which would later become Sigurjón’s land at Garðar and lived there for three years; but then Sigurjón bought two quarters of land not far from Mountain and sold his land in Garðar. The couple moved there and stayed there for a year. But Sigurjón felt uncomfortable out there on the bare plains and was used to the forest for shelter. He moved again to Þorlákur, his father-in-law to Mountain, and took over his lands. It wasn’t long after that that he bought his father-in-law’s land, and the couple lived there while they lived in North Dakota. It can be said with truth about Sigurjón Sveinsson that he was a settler, – a man who had thrown away the social life and joy of many people, and went head-to-head with the wilderness of the wasteland, where every clod of earth had to be broken, so that the forces were not overcome. He was the first settler in the southern part of the North Dakota settlement, which laughed at him, a land vast, fertile and mighty in all qualities of land and possibilities of life. Little by little, the village came together and the neighborhood grew, until Garðar – and Mountain became the most peaceful and prosperous Icelandic villages west of the sea. But Sigurjón’s longing for travel and the desire to move on grew as the crowds filled the vast village. Then it became too much for him, and he set off again in search of a new settlement. He first went west to the province of Alberta in Canada, and all the way to the Rockies. But he didn’t want to stay there and went back home. At that time, many Icelanders from North Dakota were looking for the Lakes Settlement (Vatnabyggð), located in the province of Saskatchewan in Canada. Sigurjón went there, first in search of a settlement, and as he liked it very much for there were new opportunities, he packed up his whole family from North Dakota in 1905 and moved to Saskatchewan. He had then lived in North Dakota for 25 years.

Settlement in Vatnabyggð in 1905: Sigurjón’s farm in Saskatchewan is 3 miles west of the town of Wynyard in the Lakes Settlement (Vatnabyggð). There was no railroad when Sigurjón began his farm, and it is about 50 miles from the railroad to his rightful land. On this land, Sigurjón built a good house and cultivated the land as much as possible. He made a good living there until the spring of 1909, when he lost his wife, and it was a heavy loss for him, because Valgerður was just as much a settler as Sigurjón. She had traced the settlement process of the Icelanders, so to speak, all the way from Iceland, south through the United States and finally north through the plains of Canada. She had given birth to her children at home under such hardships that only the settler woman can judge. And it was often that she kept the household together and lived with her prudence, discretion and energy, while Sigurjón stood in the fields and provided them with the things that indigenous life in sparsely populated countryside demanded. Their life hadn’t been full of flowers, as new settlers and the poverty of a double settlement; but she never lacked the will to help and admire, and from there she always drew comfort and encouragement to continue, even though the difficulties piled up. The couple’s children were still young, unmarried, when their mother passed away. Sigurjón then kept his farm for a year, but then he stopped and moved to the town of Wynyard. He ran a butcher’s shop there for 8 years, but then gave it up, and since then has spent most of his time with his children, who live in and around Wynyard.

Descendents:Sigurjón and Valgerður were blessed with seven children, and they are:

1: Henrietta, born 1884, married Friðrik Þorfinsson, son of Þorfinnur Hallsson a farmer in Mountain in North Dakota, born in Skagafjörður; Friðrik is a farmer in Wynyard, Saskatchewan

2: Páll, born 1886, married Minnie Johnson, daughter of Vilhjálmur G. Jónsson from Hjarðarfell in Dalasýsla; Páll ran a took and hardware store in Wynyard, Sask (he died 1926)

3: Lilja, born 1889, married Jón Reykdal, son of Davíð Jónasson, choir director in Winnipeg; Jon is a merchant in Wynyard, Sask and lives there.

4: Clara, born 1892, married Sigurjón Blöndal Halldórsson, son of Halldór Guðjónsson from Granastaðir in Þingeyjarsýsla; they live with Sigurjón in Wynyard.

5: Soffía, born 1894, unmarried: head nurse at the general hospital in Regina, Saskatchewan

6: Lovísa, born 1897, married Jón Jónsson Freeman, bookkeeper in Minto, N. D.

7: Aldís, born 1900, unmarried; a nurse with the Red Cross in Regina, Saskatchewan.

Epilogue: Sigurjón was young when he emigrated from Iceland in 1873, about or a little over twenty years old. In those years, there were torments and stunted vegetation in Iceland, both intellectually and physically. It was this harshness of the cold, dear country that drove many people westward in search of a gentler standard of living. Sigurjón has often mentioned the old country, and never except with a warm heart, which indicated that he had many beautiful spots in his soul from there, which had shed light on many moments of his life. But Sigurjón is happy to be able to leave his wealth, his promising children, in a gentler environment and under more loving living conditions than he was used to in his youth.

English version by Thor group.