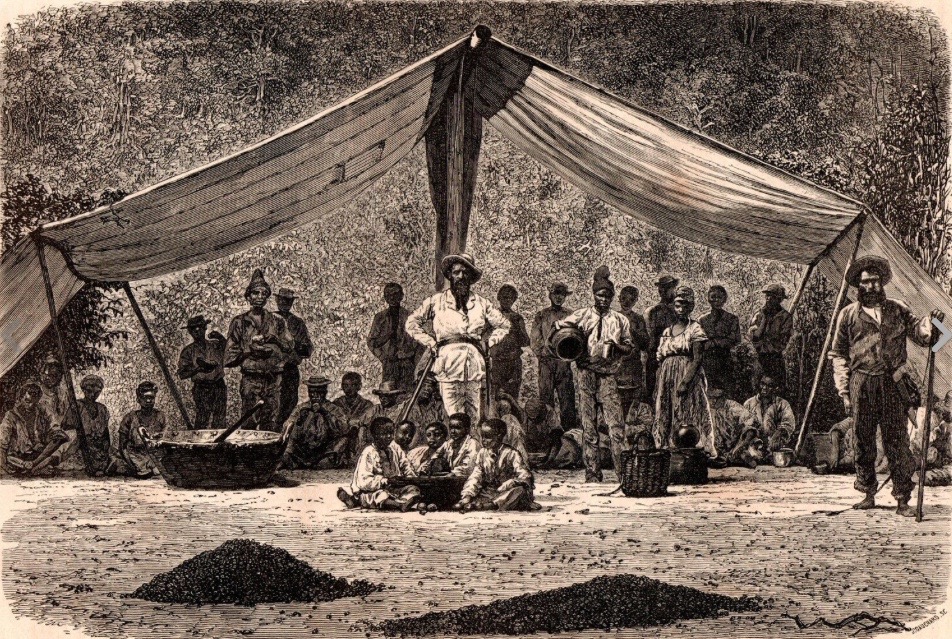

Einar had no illusions regarding the Brazilian community. He knew whites made their living on slavery. The whites numbered no more than one million but there were around “five million blacks, hispanics, or half-breeds, most of whom are slaves to the whites who all are considered noblemen or aristocrats even though the color of their skin is all they have” Einar at Nes wrote. He was obviously neither certain of the white’s superiority nor the benefits of slavery. The photo shows black slaves and their owner on a Brazilian coffee plantation about the time the first Icelanders emigrated there

Greenland never became the chosen land, at least not to any degree. The farmer at Nes, Einar Ásmundsson, saw to that. At a meeting at Hólar in Reykjadal where emigration was discussed, Einar asked for permission to speak and in a very brief speech he convinced all participants how stupid it would be to move from one cold country to another one even colder. This meeting took place in the second half of 1860, possibly later.

But which way to turn? Names of several countries undoubtedly were brought up at the Hólar meeting, Greenland the only one never mentioned again as a possible future home. West was still the desired direction and Einar appeared certain which one was the future country. Three came under consideration, Brazil, United States, and Canada, Brazil preferably “because it probably is the best country in the World” Einar maintained in a letter he wrote either in 1860 or 1861, probably thought of as an introduction of qualities each one had to offer. “Shortest distance is to Canada, but it is the coldest of the three we should be considering” stated Einar.

He had nothing to say about the weather in the United States, only they are “by far the most powerful country in the West”, where progress in everything was the greatest, there was a steady stream of immigrants from Northern Europe, English was the leading language, and huge cities as well as enormous vacant lands were found.

The third land under consideration is so large, stated Einar, that only Russia and China were larger. This is the Brazilian Empire, where winter is unheard of.

“Nowhere in the World are forests as large and numerous, where all kinds of the finest trees grow huge. In the fields, coffee, sugarcanes, tobacco, rice, maze and many more crops are grown. In some parts of the country there are treeless grassy fields where herds of wild cattle and horses roam, but throughout the country there is an abundance of wildlife and birds. Many types of metals are found in the ground, in some place mostly gold and silver but precious stones in other areas.”

Einar concluded that the distance to Brazil was five times further than to Copenhagen.

The above is based on research by Icelandic Historian Jón Hjaltason and his article ´´Einar vildi ekki Grænland´´. English version by Thor group

Grænland varð aldrei fyrirheitna landið, að minnsta kosti ekki í neinni alvöru. Til þess sá bóndinn í Nesi, Einar Ásmundsson. Haldinn var fundur á Hólum í Reykjadal til að fjalla um væntanlega búferlaflutninga. Þar kvaddi Einar sér hljóðs og sannfærði viðstadda um fáránleika þess að fara úr köldu landi í kaldara. Þetta var síðari hluta árs 1960 – eða jafnvel síðar.

En hvert átti að snúa stefnum? Eflaust hafa einhver lönd verið nefnd á Hólafundinum en víst er að eftir þann fund var aldrei talað um Grænland sem framtíðarlandið. Stefnan var þó eftir sem áður vestur. Sjálfur virtist Einar ekki í miklum vafa um hvert væri fyrirheitna landið. Þrjú komu að vísu til greina, Brasilía, Bandaríkin og Kanada. Brasilía þó helst, „því að hún er án efa eitt hið bezta land í heimi“, fullyrti Einar í bréfi sem hann skrifaði 1860 eða ´61 og var líklega hugsað sem kynning á þeim kostum sem til boða stóðu að mati bréfritara. Nefnilega Kanada en þangað er „skemmstur vegur héðan, og það land er kaldast af þeim þremur“ sem við ættum að hugsa til, sagði Einar.

Hann sagði hins vegar ekkert um veðurfar í Bandaríkjunum, aðeins að þau væru „hið langvoldugasta ríki í Vesturheimi“, þar væri mikið framfaraskrið á öllu, þangað væri stríðastur straumur innflytjenda frá Norðurálfu, enska væri aðalmálið, og að þar væru miklar borgir en líka víðlendar óbyggðir.

Þriðja landið sem hér um ræðir er svo stórt, lýsti Einar, að aðeins Rússland og Kína eru stærri. Þetta er keisaradæmið Brasilía þar sem aldrei kemur vetur.

„Hvergi í heimi eru slíkir stórskógar sem þar, og vaxa þar alls konar ágætustu viðartegundir. En í ræktaðri jörð sprettur þar mesta gnægð af kaffi, sykurreyr, bómull, tóbaki, hrísgrjónum, maís o. s. frv. Í sumum landsálfum eru skóglausar graslendur, og eru þar miklar hjarðir af villtum nautgripum og hestum, en í öllu landinu er mesti sægur af veiðidýrum og fuglum. Margs konar málmar eru þar í jörðu, á sumum stöðum einkum gull og silfur, og svo gimsteinar.“

Við þetta hnýtti Einar þeirri athugasemd að það væru um það bil fimmfalt lengra að fara til Brasilíu en Kaupmannahafnar.

Arnór Sigurjónsson: Einars saga Ásmundssonar. Bóndinn í Nesi, fyrra bindi, Reykjavík 1957, bls. 325-328.