The painting shows where the two rivers meet in Winnipeg, now called “The Forks”.

The painting dates back to 1821 and shows men ice fishing at the rivers’ junction. Fort Gibraltar, built in 1809 is on top of the hill.

Winnipeg is the capital of the province of Manitoba in Canada. The name is from the language of the natives and means “muddy water”. The city, sometimes called the “gate to the west”, is at the confluence of the Red River which flows north into Lake Winnipeg and the Assiniboine river which flows from the west. The city is thus at a crossroads, on the one hand the north-south route and on the other hand the east-west. For centuries, the rivers were the most important means of transportation for the indigenous peoples of the Canadian plain all the way west to the Rocky Mountains and to the south where the Red River joined with the Missouri and Mississippi rivers. People flocked here in their canoes, set up camp and spent the summer picking berries, hunting animals, fishing and trading. To the north of the confluence, farming was practiced. As a result, people settled here, there are indications that the oldest settlement just south of the city is 11,500 years old, but at the very point of confluence, a settlement was formed 6,000 years ago. In 1805, Canadian explorers toured the area and saw indigenous peoples engaged in farming on the banks of the Red River. In the following years, the demand for food there grew in the small indigenous settlement because the number of hunters and fur traders grew rapidly. A French explorer and fur trader, La Vérendrye, came west from Quebec and built the first fur store in the Red River Valley in 1738. The French gained a foothold in the following decades before the British Hudson’s Bay Company came into being after the Seven Years’ War in the mid-18th century. Many French men married women of indigenous peoples, whose children followed the traditions of indigenous peoples, engaged in fishing and barter. As the years passed, a special ethnic group, “Métis”, emerged which made a great impression on the community not only in the city but also in the entire province.

British influence: Scottish man Thomas Douglas inherited the throne of the county of Selkirk in south-east Scotland. He felt sorry for the homeless Scots and in the early 19th century he turned his eyes west across the ocean. He bought land in Eastern Canada and moved people to the West. He continued to buy land and was the first European to establish a colony in the Red River Valley called the Red River Colony. The land allotted to him was large, reaching far south into present-day N. Dakota and Minnesota and west to the provincial borders of Manitoba and Saskatchewan. The land between Lake Manitoba and Lake Winnipeg (the Interlake) also belonged to Lord Selkirk. He got the land from the Hudson’s Bay Company, which saw a great opportunity to promote agriculture on the plains instead of having to transport supplies there from Britain. The company’s condition for this agreement was that 200 people would be present in the colony and that Lord Selkirk would not be involved in fur trade. The Hudson’s Bay Company was not the only company on the plains; in 1779 the so-called North West Company was founded in Montreal. Both companies settled in the Red River Valley, the North West Company built a trading post (fortress) called Fort Gibraltar in 1809 and the Hudson’s Bay Company Fort Douglas in 1912. The competition was fierce but in 1821 the Hudson’s Bay Company took over the North West Company, Fort Gibraltar was given the name Fort Garry which today is a large suburb in Winnipeg. In 1870, Manitoba became the fifth province in the three-year-old nation, Canada, and Winnipeg, the capital of the plain.

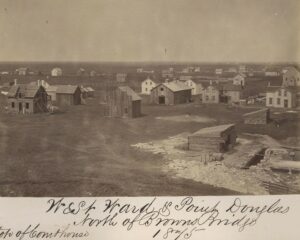

This is Point Douglas in Winnipeg in 1875. Many Icelanders settled in such a district called Hudson´s Bay Flats. Such huts were called Shanty Towns.

Icelanders settle: The first Icelanders to settle in Winnipeg arrived in October 1875. They were in the first group to settle in the wilderness on the west bank of Lake Winnipeg. To settle in the wilderness of Manitoba so late in the fall was considered by many in the city to be the greatest delusion. As a result, the group’s tour guides encouraged young girls and single men to explore the possibility of staying in the city, with family members continuing in the community. ÞÞÞ says in SÍV2 p. 321 that there were 50-65 people left in Winnipeg, most of them young women, as their employment opportunities were much better than those of young men. Sources do not agree on families because ÞÞÞ says only Björn K. Skagfjörð has remained in the city with his wife and three sons. A letter from a settler in New Iceland published by the Winnipeg Free Press on January 17, 1876 states that about 50 families settled in the colony by the lake, with a total of 60 or so arriving in the city in October. The girls and young women were accommodated almost effortlessly in the homes of established families in the city, but boys and young men worked on unloading or chopping wood for house heating. In August a year later, another large group came to Winnipeg directly from Iceland and the majority went to New Iceland, but some remained in the city. In less than a year, more than one thousand Icelanders settled on the plains in a society that was changing rapidly. In the years 1877-1901, a few joined the Icelandic community in Winnipeg every year. Some came from Markland in Nova Scotia, Ontario, or from various parts of the United States. Some also came directly from Iceland every year. Finally, it should be mentioned that those who gave up the hardship in New Iceland, moved to Winnipeg and lived there for a while looking for other places. Many never left the city.

The construction of the train station in Winnipeg was completed in 1884. This became the destination for thousands of Icelandic immigrants. throughout the Emigration Period ending in 1914. People expecting relatives from Iceland waited here, others also showed up in order to meet fellow countrymen arriving from the old country.

Railroad-Winnipeg Blooms: The government agreed to build a railroad across Canada westward and across the Rocky Mountains to the west coast. In 1880, the CPR’s railroad was approaching Winnipeg, and at this significant juncture, the Canadian Plain opened to the west. It was clear to everyone that in the following years, the number of immigrants who migrated to the west would increase, so it can be said that this large area was the only one in all of North America that was not occupied. In the following years, Winnipeg became a hub for manpower and freight. The business community took off, the development and increase of the population was like a fairy tale. Let’s look at what Tryggvi J. Oleson wrote about Íslendingabrask in the city: “People believed that the city would have a great and glorious future, and then there was a great desire to buy plots, which they could then sell with profit after a while. Icelanders immediately took an active part in this profiteering, and many of them made money. There was also plenty of work, because houses sprang up on every corner, and it was easy to get enough to do. The salary was good – about $3.25- $3.75 per day.” (SÍV4, p. 347) Here it is appropriate to pause and consider only the western migrations of Icelanders until the year 1880, their ideas and expectations. The dream of most in this first decade was to take part in the formation of an Icelandic colony where people had the opportunity for agricultural work and even fishing. This had been the livelihood of the Icelandic westerner from a young age, he did not have much knowledge or experience in the field of complex business life on a foreign land. It is noteworthy, however, that among the Icelandic immigrants in Winnipeg in 1880 were individuals who had this in their blood. People did not settle in Winnipeg for digging ditches, sawing wood, or laying railroads for life, including young men who went west to make a better life for themselves and their families. It was also revealed early in the Emigration Period that agricultural work was not suitable for everyone.

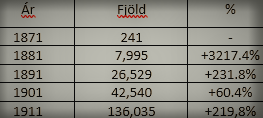

This table shows the population growth in Winnipeg from 1871 to 1911.

Let’s look again at what Trggvi said further: “The first Icelander to buy a plot of land after this turmoil began was Helgi Jónsson, later Leif’s editor. Then he must have bought and sold each one after the other. He is also believed to have been the first Icelander to build a house in Winnipeg …. Jón J. Júlíus was the name of another Icelander who took part in these purchases and sales. He bought two plots on Jeminastræti for $400.00 and built a house on them for $250.00. He then sold the entire property with a $500.00 profit.” Women were just as involved. Tryggvi writes: “Guðrún Jónsdóttir also took part in this profit brawl. She started with $20.00, bought a plot of land and had a house built. She rented this house for two months for $12.00 a month and later sold it for $1000.00. She made $400.00 on this business.” (SÍV 4 p. 348). This success led to the founding of a society on November 1, 1881, called the “Profit Society,” and it prospered, but massive floods in the Red River throughout the city were followed by a snowy winter, and suddenly the future prospects for Winnipeg were anything but glorious. Real estate prices collapsed and the finance company Gróðafélagið ended up with plots that no one looked at. At the beginning of 1883, this Icelandic adventure ended in Winnipeg.

Adapting in Winnipeg – Icelandic Society: When Icelanders established themselves in the multicultural community in Winnipeg in the 1880s and took an active part in the formation of society, it was clear that they had chosen a different path in the West than their cousins, brothers or fellow countrymen did in the rural communities in Minnesota, N. Dakota, and New Iceland. It is said that 14-17 different languages could have been heard on the streets of Winnipeg around 1880, including various indigenous dialects. This is an indication of the social pattern that existed in the city at that time. It became clear to all immigrants, no matter where they came from, that in order to achieve their goals and create a better life for themselves and their families than they could in their home country, they had to adapt to the laws and regulations set by both the Canadian and provincial governments. One of the most important elements in this feature was the language, the language of the ancestors in the homeland was set aside in the daily routine of city life where English had to become the dominant language. At home, parents used their father tongue among themselves but made sure that their children mastered English. The key to the future of youth was a good command of the English language. Men in road work, railway construction, or digging ditches soon learned that their superiors used English customs and addressed individuals by their father’s name. The story was told in Winnipeg that once, before the turn of the century, 11 Icelanders had worked together in road work, of whom 8 were Jónsson. When the foreman had something to say to one of them, he called “Jónsson” and then 8 Jónssons jumped to their feet and answered the call.

Icelanders in Winnipeg soon began to settle in various places in the city, but their common place was two guesthouses on Main St. which were both called Íslendingahús. This was the birthplace of a society that probably has its roots in the house readings of Jón Þórðarson from Eyjafjörður. He and his wife, Rósa, ran another guesthouse and restaurant. No Icelandic congregation had been formed during these years (1876-1877), people sought to hear the word of God, some in churches of other ethnic groups but many came to Jón on Sunday morning for that purpose. The first Icelandic society was founded in Winnipeg on September 6, 1877 and was given the name “Icelandic Society”. Reverend Friðrik Bergmann writes about the society in Ólafur Þorgeirsson’s Almanak in 1903 and says: “The society’s law states that is to “strengthen and preserve the dignity of the Icelandic heritage on this continent, to maintain and promote among Icelanders the free spirit of progress and education, which in all centuries of history has characterized the Icelandic nation”. It is easy to agree with the pastor when he says: “The intention seems to be quite extensive and undecided and it is obvious that people’s ideas about fellowship have been rather childish at those times. But it should be noted that such were the by-laws of all social ideas among our nation at this time.” The association had a fairly successful childhood and adolescence, but then began to lose ground. In 1881, the name of the association was changed to “Framfarafélagið” and it operated continuously until the end of 1884, but then disunity within the association brought it to an end. It accomplished many good things during its lifetime, it made an effort to keep track of all the Icelanders who came to the city, organized all kinds of gatherings and ran schools that taught young and old English. Another notable association was founded in Winnipeg in the summer of 1881, it was a women’s association. A few women then came together and organized a lottery that went well and there was general satisfaction with the initiative. It was on October 1 that a formal women’s association was founded in Winnipeg and the association’s first task was to stage the play “Sigríður Eyjafjarðarsól” and with the profits they formed a social fund. Reverend Rögnvaldur Pétursson once heard a story from the founding of the society and says: “It was the beginning of this society, according to one of the founders, that some women and girls went one day late in the summer west of the town for fun, west onto the vast grassy plain that extends as far as the eye can see north and west of Winnipeg. Once out on the plain, they sat down and began to discuss the circumstances of the immigrants and others in the town. They then agreed that they should establish an association among Icelandic women in Winnipeg, and that the association should do its best to help unemployed people and those companies that could protect young and old from landing in the gutter. These women were Rebekka Guðmundsdóttir and her daughter Guðrún Jónsdóttir, Kristrún Sveinungadóttir and her daughter, Svava Björnsdóttir, Þorbjörg Björnsdóttir, Signý Pálsdóttir, Helga Jónsdóttir and Hildur Halldórsdóttir.” Rebekka was elected president of the association, Svava secretary and Signý treasurer. The association worked diligently on welfare issues, especially when it came to helping newcomers from Iceland for the next 5-6 years.

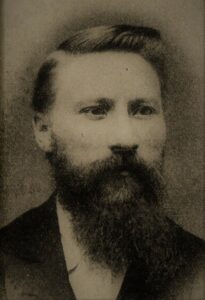

Rev Jón Bjarnason in Winnipeg in 1878.

Icelandic congregation: Reverend Jón Bjarnason was very influential in the West, both in 1873-1880 and 1885-1914. He became a priest in New Iceland and sang his first Mass in Winnipeg on October 28, 1877. Reverend Páll Þorláksson also performed various priestly works, e.g. he married the first Icelandic couple in Winnipeg on September 6, 1876, but he also served congregations in New Iceland. They both sang Mass in Winnipeg from time to time during their stay in New Iceland, but Reverend Páll moved with his congregation in 1878 and Reverend Jón moved to Iceland in 1880. Reverend Jón encouraged the formation of an Icelandic congregation in Winnipeg and it was formed on August 11, 1878 and called the Trinity Church. Reverend Halldór Briem moved to Winnipeg from New Iceland and sang Mass, but then returned to Iceland in 1881. The activities of the congregation were minimal until Jón returned to the West and came to Winnipeg in early 1884. He immediately began to build up congregational work and almost 183 souls had registered in the congregation in the autumn of 1884. A census conducted by Icelanders themselves in March 1884 states that their number in the city is 857. There is some breakdown and number in various industries as specified: 12 are merchants, 10 carpenters, 1 is a blacksmith, 3 are painters, 4 are printers, 3 are shoemakers, 5 are musicians and 12 girls are seamstresses. (SÍV4, p. 355).

Newspaper in Winnipeg: Speculation about an Icelandic newspaper began in Winnipeg shortly after the publication of Framfari was stopped in New Iceland in 1880. Various entrepreneurs in the city, e.g. Jón Júlíus, Magnús Pálsson and Helgi Jónsson, discussed the matter and explored various options. They wrote to an Icelandic student from the University of Iowa and sought his desire to become the editor of an Icelandic newspaper in Winnipeg. Reverend Friðrik J. Bergmann wrote an article in the Almanak of Ólafur Þorgeirsson in 1903 about the newspaper “Leifur”, which began in the spring of 1883. The priest says: “They invited him (the student from Iowa) to their meeting and had a lot of talk about an Icelandic newspaper company. But the result was that it was not possible to raise so much money that it would be worthwhile to invest, and at the same time it would be possible to pay decently for editorial and other work for the paper. This case was dropped for the time being.” Helgi Jónsson was the only one who thought that the publication of a paper in Winnipeg could work, and he started publishing it on May 5, 1883 and edited the paper himself. We hear what he says in an address to readers in the first issue: “I want to draw your attention to the fact that if I let this company fail, then it is to be hoped that an Icelandic weekly newspaper will be seen printed here on this side of the Atlantic and I will quit, it will be safe for anyone to start, because there are not many of us here who can invest as much money as needed to publish a paper for free. That is why I would like to ask people, if they think something is wrong with the paper, to show me the shortcomings so that I can remedy them, and also send good essays to it instead of stopping buying it. In order for the paper to be able to carry itself and those working for the paper have a decent salary, which does not mean that it has 15.00 (sic) (as written in the paper, there should be 1,500. Aside from JÞ) subscribers. This will now be considered a fairly high number, and unlikely to be obtained, as “Framfari” never had more than 600 subscribers in all and there were only 300 of them on this side of the Atlantic: but I want to say that as there were 300 Icelanders able to buy Framfari in its day, here on this side of the ocean, as many as 3,000 should be able to buy this paper nowadays, and it clearly shows that if the company is left stranded, it is only for the indifference of men. Finally, I want to let you know, dear countrymen! It’s not my own money that I’m hurt by even if I lose, because even though I lose $1 to 2,000 on the company, I’m still standing as before, and I’m much happier to lose it on this company, than anyone giving me financial support for nothing. It is the Icelandic nation that I am thinking of; it is she who loses more than I do by not being able to have a good newspaper in her own language.” Reverend Friðrik writes in the conclusion in his article: “even though both the style and spelling need improvement, and despite these flaws, it is still amazing that it isn’t even worse. But the general opinion was that the launching of the paper was poorly planned, and many people ignored the appeal to subscribe to it or subsidize it in some other way. But it did not occur to the editor to give up on it.” It soon became clear that many thought Helgi was taking a big chance and strongly criticized the publication. In the autumn of 1883, Helgi succeeded in convincing the Ottawa government to buy 2,000 copies of the paper for distribution in Iceland, and many considered it too far-fetched. Meetings were held during the winter and next summer (1884) where Helgi’s opponents collected signatures on a document to the Government of Canada stating that she would stop buying the paper if the editor did not change his policy. Helgi defended well, himself collecting signatures on a document in which individuals expressed satisfaction with the paper and its policy. Helgi got various powerful men to sign up, e.g. Rev. Jón Bjarnason, Árni Friðriksson, Friðjón Friðriksson and Sigtryggur Jónasson. During the following months, the publication continued to lose support and Leifur‘s last issue was published on June 4, 1886. Helgi always had a lot of irons in the fire and gradually all his attention was focused on a new settlement area in the west where he saw opportunities for a new Icelandic colony. He moved from Winnipeg and settled in Langenburg, which is now a town in Saskatchewan. He died there in the autumn of 1887, aged 35 years.

The battlefield in 1885

Integration and Icelandic values: These controversies about Leifur clearly show the division that had developed in the relatively small community of Icelanders in the city. In Winnipeg, Icelanders took an active part not only in the affairs of the city but also of the province as a whole. Here was a welcome freedom to express their views and fight for ideals. Before the end of this decade, two new Icelandic weekly newspapers had been published, Heimskringla started publication on September 9, 1886 and Lögberg on January 14, 1888. There was a split in religion, some remained loyal to Reverend Jón Bjarnason and his congregation, others joined Björn Pétursson’s Unitary Church, founded in Winnipeg on February 1, 1891. In Winnipeg, the first and greatest steps were taken in the integration into Canadian society. A good example is the participation of Icelanders in the revolt of half-breeds and Indians in 1885. To explain further, we must go back to the year 1870, when half-breeds led by Louis Riel rebelled against the government when the land was being surveyed and settlement on the plain was planned. That dispute was resolved without bloodshed and an agreement was made with half-breeds. In 1885, the story was repeated while surveying and planning of the prairie took place in what is now Saskatchewan, west of Manitoba. Rebels, half-breeds, and various tribes of Indians soon took up arms. Young Icelandic men in Winnipeg then joined the army and fought for the first time with their Canadian brothers in the Canadian army. No Icelander fell but one was wounded, received a bullet in the arm and was sent off the battlefield. The Icelanders in Winnipeg welcomed their countrymen when they returned, gatherings were held in their honor and on June 1, 1885, Sigurður J. Jóhannesson writes in Leifur, that he wants all Icelanders to testify: “These young warriors are worthy of public gratitude, especially for how bravely they have maintained the reputation and respect of our nation, and as restored it to its ancient military fame.” The integration into Canadian society in Winnipeg appears in various other forms e.g. when flipping through Icelandic weekly newspapers in the years 1882-1890, it is clear how people sign for their articles and poems; S. Sigurðsson instead of Sigurður Sigurðsson and K. Stefánsdóttir instead of Kristín Stefánsdóttir. Einar Hjörleifsson was Lögberg’s first editor and says in one of his first editorials: “Most people have two names, Icelandic and non-Icelandic. Of course, they use the Icelandic names when they are around their countrymen, but they abandon them as soon as they are in front of a foreigner, or someone other than their countrymen. Then they resort to what they call “in English.” However, it is not at all understandable that everyone is content with two names. Some call themselves countless names. One is called e.g., Sveinn Grímsson, when he comes here from Iceland. He calls himself Svein Grímsson in such an everyday way, when he is around Icelanders. But he has another special name, e.g., Sveinn Vestmann and he uses it e.g., when he has to write his name, or on other very solemn occasions. But among the locals he is not called Sveinn nor Grímsson or Vestmann. To begin with, he probably asks the Englishman to call him John Anderson. Then he gets bored with that name, and when he moves to someplace and is among strangers, he takes the opportunity and starts calling himself Thomas Edison or George Brown.”

Integration and Icelandic values: These controversies about Leifur clearly show the division that had developed in the relatively small community of Icelanders in the city. In Winnipeg, Icelanders took an active part not only in the affairs of the city but also of the province as a whole. Here was a welcome freedom to express their views and fight for ideals. Before the end of this decade, two new Icelandic weekly newspapers had been published, Heimskringla started publication on September 9, 1886 and Lögberg on January 14, 1888. There was a split in religion, some remained loyal to Reverend Jón Bjarnason and his congregation, others joined Björn Pétursson’s Unitary Church, founded in Winnipeg on February 1, 1891. In Winnipeg, the first and greatest steps were taken in the integration into Canadian society. A good example is the participation of Icelanders in the revolt of half-breeds and Indians in 1885. To explain further, we must go back to the year 1870, when half-breeds led by Louis Riel rebelled against the government when the land was being surveyed and settlement on the plain was planned. That dispute was resolved without bloodshed and an agreement was made with half-breeds. In 1885, the story was repeated while surveying and planning of the prairie took place in what is now Saskatchewan, west of Manitoba. Rebels, half-breeds, and various tribes of Indians soon took up arms. Young Icelandic men in Winnipeg then joined the army and fought for the first time with their Canadian brothers in the Canadian army. No Icelander fell but one was wounded, received a bullet in the arm and was sent off the battlefield. The Icelanders in Winnipeg welcomed their countrymen when they returned, gatherings were held in their honor and on June 1, 1885, Sigurður J. Jóhannesson writes in Leifur, that he wants all Icelanders to testify: “These young warriors are worthy of public gratitude, especially for how bravely they have maintained the reputation and respect of our nation, and as restored it to its ancient military fame.” The integration into Canadian society in Winnipeg appears in various other forms e.g. when flipping through Icelandic weekly newspapers in the years 1882-1890, it is clear how people sign for their articles and poems; S. Sigurðsson instead of Sigurður Sigurðsson and K. Stefánsdóttir instead of Kristín Stefánsdóttir. Einar Hjörleifsson was Lögberg’s first editor and says in one of his first editorials: “Most people have two names, Icelandic and non-Icelandic. Of course, they use the Icelandic names when they are around their countrymen, but they abandon them as soon as they are in front of a foreigner, or someone other than their countrymen. Then they resort to what they call “in English.” However, it is not at all understandable that everyone is content with two names. Some call themselves countless names. One is called e.g., Sveinn Grímsson, when he comes here from Iceland. He calls himself Svein Grímsson in such an everyday way, when he is around Icelanders. But he has another special name, e.g., Sveinn Vestmann and he uses it e.g., when he has to write his name, or on other very solemn occasions. But among the locals he is not called Sveinn nor Grímsson or Vestmann. To begin with, he probably asks the Englishman to call him John Anderson. Then he gets bored with that name, and when he moves to someplace and is among strangers, he takes the opportunity and starts calling himself Thomas Edison or George Brown.”

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(40)/discogs-images/A-5882071-1570071076-3521.jpeg.jpg)

Einar Hjörleifsson

Einar wants people to keep their first name at all costs, but other things can be changed. He says elsewhere: “We are in conflict with the most powerful nation in the world. We ourselves are few and poor, so it is no wonder that we have to ease our standards to some extent. When people are at war, it is often beneficial for them to make peace in time. In this way, people often get what they would otherwise lose. It all depends on people realizing in time what they must lose and what they can keep. We have to give up the daughter’s name. We must stop using for the baptismal names our fathers first name, if not in this generation, then in the next. But we can keep Icelandic names and we should keep them.” Let’s finally hear from Einar, he said this in a speech in Winnipeg on February 8, 1889 and mentioned call the lecture: Are we going to disappear into the crowd? “On the other hand, I also claim that it would be detrimental to the national life of our new homeland if we did not resist and let it be swallowed up just as we stand. If we turn into what are poor, ignorant foreigners, then we make no contribution to it, except our bodies. Our spiritual forces are transformed after the heads of the people of Heaven, plunged into the same mold as themselves. But if we have the stamina and endurance to resist, until freedom and all the glorious qualities of this land have made us new and better men, without depriving us of anything that could not be lost from us and was ours. It also happens that where the Englishman and the Icelander meet in the national life of this country, two equally capable boys meet. One does not bow to the other, but both bow to each other. It will not be one who pressures the other into what he stands for, but two equally free-born men interact on each other as equals. We do not then disappear into domestic society in any way any more than domestic people into our national life – other than there will be more of them. And if we vanish into a new nation – if people want to call it that – in such a way that we contribute to the best that is and will be in ourselves, and get back the best that is and will be in the hearts of men, then we have not disappeared like a drop into the sea, unless something is understood by it other than what I understand by it.” (SÍV4 422-423)

English version by Thor Group.