State of Utah: Utah is located in western USA, surrounded by the states of Idaho, Wyoming, Colorado, New Mexico, Arizona, and Nevada. The area features multiple mountain ranges, deserts, and Great Salt Lake, with mostly hot, dry, and flat valley bottoms between the mountains. Icelandic settlement occurred near Spanish Fork, in the favorable agricultural land of north-central Utah, as well as Springdale in southern Utah, near the Arizona border. H. Thorleifson.

From Fremont Indian State Park, Utah

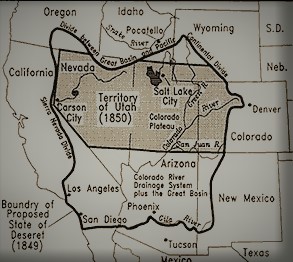

Native Americans adapted to local customs and lived their lives in various ways. The area that later became Utah was mostly desert, but two tribes, the Pueblo and the Fremont, shared the area in question and their lifestyles were different in many ways. Pueblo dwellings were in caves or caverns in cliffs, while the Fremont built straw or log houses. The first Europeans to enter the area were Spaniards in the 16th century, and while they were frequent visitors there for the next two centuries, but they never settled there. Other indigenous peoples, such as Navajo, Ute, and Shoshone, did so in the 18th century. These indigenous peoples did not welcome the arrival of Europeans in the area, and it was not until the 19th century that the indigenous peoples kept their lands. The United States was more successful in the war with Mexico in 1848 and the so-called Utah Territory was created. The map shows the territory as well as the possible borders of a new state, the State of Desert, which covered parts of Nevada, Idaho, Wyoming, Colorado, New Mexico, Arizona and California. The state in this image was not created, but at that time a group of Mormon believers had found the Promised Land in the area.

Native Americans adapted to local customs and lived their lives in various ways. The area that later became Utah was mostly desert, but two tribes, the Pueblo and the Fremont, shared the area in question and their lifestyles were different in many ways. Pueblo dwellings were in caves or caverns in cliffs, while the Fremont built straw or log houses. The first Europeans to enter the area were Spaniards in the 16th century, and while they were frequent visitors there for the next two centuries, but they never settled there. Other indigenous peoples, such as Navajo, Ute, and Shoshone, did so in the 18th century. These indigenous peoples did not welcome the arrival of Europeans in the area, and it was not until the 19th century that the indigenous peoples kept their lands. The United States was more successful in the war with Mexico in 1848 and the so-called Utah Territory was created. The map shows the territory as well as the possible borders of a new state, the State of Desert, which covered parts of Nevada, Idaho, Wyoming, Colorado, New Mexico, Arizona and California. The state in this image was not created, but at that time a group of Mormon believers had found the Promised Land in the area.

Mormons: In the United States, there was never a national church, but immigrants who immigrated for religious beliefs, had to form their own congregations, build churches and hire priests. Religious groups in Europe settling in America, were allowed to be at peace with both the public and the government. But religious freedom is a problem, and in the early 19th century, when the influx of immigrants to the United States from Europe began to take hold on the East Coast, various Christian congregations began to dispute which doctrine was the correct doctrine. The national church in its homeland in Europe was no longer dominant, the freedom in America covered not only practical activities but also religious beliefs.

Joseph Smith was born into this world in 1805, and because of his poverty and deprivation and large family, his schooling was short-lived. His parent’s main concern during his upbringing was a strong emphasis on Bible reading. The family lived in Palmyra, New York, where various denominations and congregations competed to reach the public with their message. Such efforts had affected Joseph, but he withstood all stimuli. Mormon history says God and Jesus appeared to Joseph when he was 15 years old and told him to restore the one true Church of Christ. This is what Joseph did, and the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints was created. Naturally, Joseph needed to introduce his congregation, the Mormon Church, and he soon became embroiled in controversy, but his congregation grew and prospered. The situation on the east coast led Joseph to turn west, and the congregation grew further. In the years 1830-1831, there was a theory that somewhere in America was the Promised Land of Mormon and Joseph set up a base in Ohio where he remained until 1838. The road to Utah was rocky because in the following years there were great upheavals within the Mormon Church as well as constant quarrels with other religions and governments. Joseph was executed without trial on June 27, 1844, when an angry mob stormed the prison while he and his brother were awaiting trial. Brigham Young took over at this difficult time in the history of the Church. Almost relentless persecution made it very difficult for Mormons everywhere. Brigham had no doubt been aware for a long time that the Mormon Church was nowhere to be found in the eastern United States, and Mormon history tells us that he was told that the Promised Land was in an area that belonged to Mexico. To make a long story short, the Mormon settlers first reached the Salt Lake Valley on July 24, 1847. The United States conquered northern Mexico in 1848, and Brigham was made governor of the Utah Territory. In the years 1847-1869, it is estimated that more than 70,000 Mormons migrated to Utah, and at the same time missionaries were traveling not only through the United States but also to Europe.

Þórarinn Hafliðason drowned in the Westmann Islands in 1852. Photo: FoI

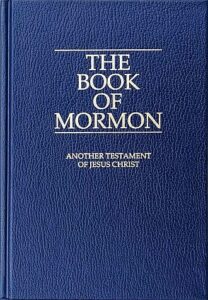

Mission – The Beginning in Iceland: Mormon leaders in Utah immediately realized that it took a lot of labor to turn the desert in Utah into the garden that was to be built. Despite bringing slaves with them and enslaving indigenous people in the district, many more were needed. It was therefore not only a new religion that missionaries were to preach, but also to encourage people to go west, to the bliss of a new world where everyone was equal in one flock, each with his own land. In October 1849, Mormon leaders in Salt Lake City agreed to send missionaries to Europe. One would take care of Germany and Austria, another Italy and France, but three would take care of the Nordic countries, two for Denmark and one for Sweden. The Danish brothers, Hans Christian and Peter O. Hansen, were instrumental in translating the Book of Mormon into Danish, the first translation of this significant book into another language. The two missionaries in Denmark were Erastus Snow and the Danish Peter O. Hansen. The former caught the ear of Guðmundur Guðmundsson, an Icelandic student in Copenhagen. Einar Hermann Jónsson (E. H. Johnson) from Þistilfjörður settled in Spanish Fork in Utah in 1890 and soon became very interested in the history of Icelanders in Utah. He wrote an article about this in the Almanak published in 1915. There he says; “It will therefore be the beginning of our history here, that around 1850, two Icelanders in Copenhagen were learning their craft. Their names were Þórarinn Hafliðason and Guðmundur Guðmundsson. They both lived in the Westmann Islands and have probably been descended from there, or from the Landeyjar. I do not know whether it is more correct, but the other is reliable, that they were in Copenhagen during this period and took the faith there, which is called “Mormon”, and Utah is nowadays most famous for. I also do not know how long these men stayed in port; but Magnús Bjarnason mentions them in his biography and says that it was at that time, and that Þórarinn was the first Icelander to convert to the Mormon faith, and therefore the rightfully named father of that religion among Icelanders. Guðmundur Guðmundsson, a goldsmith, and Þórarinn’s companion, who later moved to Utah, was the next, and they then went home to their land of their youth and began to preach the new faith to their friends and relatives there on the islands, which at first went rather slow, but came true over time and mainly caused countrymen to start moving to Utah. Two or three families on the islands immediately joined this faith, and from that group was the man who was the first Icelander to move to Utah.”

Mission – The Beginning in Iceland: Mormon leaders in Utah immediately realized that it took a lot of labor to turn the desert in Utah into the garden that was to be built. Despite bringing slaves with them and enslaving indigenous people in the district, many more were needed. It was therefore not only a new religion that missionaries were to preach, but also to encourage people to go west, to the bliss of a new world where everyone was equal in one flock, each with his own land. In October 1849, Mormon leaders in Salt Lake City agreed to send missionaries to Europe. One would take care of Germany and Austria, another Italy and France, but three would take care of the Nordic countries, two for Denmark and one for Sweden. The Danish brothers, Hans Christian and Peter O. Hansen, were instrumental in translating the Book of Mormon into Danish, the first translation of this significant book into another language. The two missionaries in Denmark were Erastus Snow and the Danish Peter O. Hansen. The former caught the ear of Guðmundur Guðmundsson, an Icelandic student in Copenhagen. Einar Hermann Jónsson (E. H. Johnson) from Þistilfjörður settled in Spanish Fork in Utah in 1890 and soon became very interested in the history of Icelanders in Utah. He wrote an article about this in the Almanak published in 1915. There he says; “It will therefore be the beginning of our history here, that around 1850, two Icelanders in Copenhagen were learning their craft. Their names were Þórarinn Hafliðason and Guðmundur Guðmundsson. They both lived in the Westmann Islands and have probably been descended from there, or from the Landeyjar. I do not know whether it is more correct, but the other is reliable, that they were in Copenhagen during this period and took the faith there, which is called “Mormon”, and Utah is nowadays most famous for. I also do not know how long these men stayed in port; but Magnús Bjarnason mentions them in his biography and says that it was at that time, and that Þórarinn was the first Icelander to convert to the Mormon faith, and therefore the rightfully named father of that religion among Icelanders. Guðmundur Guðmundsson, a goldsmith, and Þórarinn’s companion, who later moved to Utah, was the next, and they then went home to their land of their youth and began to preach the new faith to their friends and relatives there on the islands, which at first went rather slow, but came true over time and mainly caused countrymen to start moving to Utah. Two or three families on the islands immediately joined this faith, and from that group was the man who was the first Icelander to move to Utah.”

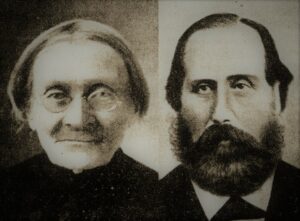

Helga Jónsdóttir andÞórður Diðriksson Photo: Almanak 2015

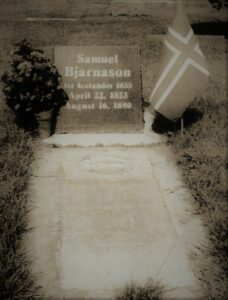

Samúel’s grave in Spanish Fork, Utah Photo: FVTV

Emigration begins: Þórður Diðriksson was born in Rangárvallasýsla on March 26, 1828 and grew up in Landeyjar. His brother was Árni Diðriksson in Stakkagerðir in the Westmann Islands and Þórður would have gone to him in 1849. He is therefore on the island when the religious brothers Þórarinn Hafliðason and Guðmundur Guðmundsson come there from Copenhagen to start a mission. It was Loftur Jónsson in Stakkagerðir who baptized Þórður on February 17, 1855. Þórður later said that he was immediately impressed by the speeches of the missionaries, like most others who listened to them, he had listened to them three times and felt how their case fascinated him. However, he fought an inner struggle, because if he took this faith, how could he live with all the contempt, even hatred that so many showed. Undoubtedly, this hastened his decision to leave the country and settle in Utah, because in July of the same year, Þórður sailed to Copenhagen. Missionary Guðmundur Guðmundsson also went to Copenhagen this summer, and near the end of the year they travel west across the ocean. According to Þórður’s travel story they came to New York in the second week of March in 1856. (See Íslensk Arfleifð Fragments from Þórður Diðriksson’s Travel Story). One of them was Samúel Bjarnason in Kirkjubær in the Westmann Islands and his wife, Margrét Gísladóttir. They went to Copenhagen in the summer of 1854 and their friend, Helga Jónsdóttir from Landeyjar, accompanied them. They stayed in Denmark for a while before going to England where they boarded the James Nesmith in Liverpool and sailed from there on January 7, 1855. They arrived in Salt Lake City in Utah on September 7, 1855. Helga stayed there but the elders pointed Samuel to Spanish Fork because there were then quite a number of Danish Mormons. Brigham Young thought it wise for Icelanders to settle with cousins from Denmark. The couple chose a plot of land in the southeastern part of the town and built a house there. He was allocated an 160 acres and is rightly considered the first Icelandic settler in Utah. Samuel prospered, farming a large flock of sheep.

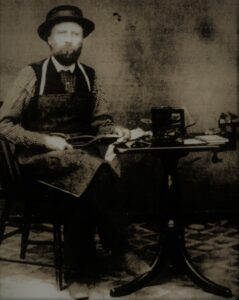

Guðmundur at his studio in Utah. Photo:FVTV

Joseph Morris

Guðmundur Guðmundsson met a Danish couple on their way across the Atlantic, Niels and Marie Garff, who were also Mormons on their way to Utah. They came to the United States and traveled the land route to Iowa City, Iowa, but the desolation from Nebraska to Utah proved difficult for Niels and his daughter, they became ill and both died in the desert. Guðmundur promised Niels to take care of his wife and three sons and he kept it because he married Marie in Salt Lake City on October 4, 1857. They first settled in Spanish Fork but after two years they went to Salt Lake City where Guðmundur opened a studio. He met Nordic Mormons who had joined Joseph Morris who claimed that Judgment Day, the return of Christ, was approaching. Would they have leave the Mormon faith?

Guðmundur led this group of fellow believers from the Nordic countries, sold his house in Salt Lake City, and settled in Farmington. Morrisite’s message, as Joseph Morris’ followers were called, did not gain popularity in Utah, so the movement disintegrated, Joseph Morris fell in disrepute, and many of his followers were arrested, including Guðmundur. He was brought before a judge and charged with resisting arrest. He was sentenced to a fine of one hundred dollars. They continued to live in Farmington, but in 1868 Guðmundur moved with his family to Sacramento, California to find a cure for Decan Westmorland, Marie’s son. He had been suffering from a long-term illness and there he received adequate treatment. While he was recovering, Guðmundur and Marie were given the opportunity to reflect on the future, she desperately wanted to return to Utah so that Decan could be blessed by the pastors to complete his recovery. Guðmundur was worried about the doctor’s costs, thinking that he would have to work in Sacramento to be able to pay doctors. But then a miracle happened. Decan made a friend and together they looked at an old building, a half-round sawmill, and under the floorboards they found sacks full of money. Guðmundur announced the find to the authorities, who paid him a finders fee, which was not only enough to pay the doctors, but also the cost of moving back to Utah. They settled in the town of Draper, where they lived for two years before moving to Lehi. Guðmundur bought a house, opened a shop, and worked as a goldsmith. He was reconciled and baptized again into the Mormon congregation.

This is Loftur Jónsson’s house built around 1860 in Spanish Fork. In front are three prominent women: Margrét Gísladóttir, the first Icelandic woman in Utah is on the far right, next to her in the middle is Halldóra Árnadóttir, the wife of Gísli Bjarnason, who is standing behind. She was the widow of Loftur. Guðrún Jónsdóttir, Loftur’s stepdaughter, is the third woman. Photo: FVTV

Loftur Jónsson was converted by the Mormons in 1853 in the Westmann Islands, where he took over the leadership of the Mormons from Guðmundur Guðmundsson. In 1857, he left for Utah with his wife and two children. They came to New York and from there went by land to St. Louis. It turned out that the next planned trip to Utah would not be in the near future, so Loftur found a place to stay for the family and soon found work in construction. He was considered equally good at wood and iron. There was a lot of development in the city and Loftur had plenty to do and got paid well. It was on June 13, 1859, that they set out from St. Louis in a large Mormon group of various nations. Their goods were placed on a cart pulled by Loftur. There were 59 wagons pulled by 104 pairs of oxen, 11 horses, 35 dairy cows and 41 calves. Loftur later wrote back to Iceland and said that supplies for the masses had been sufficient for the 72-day trip. When they came to Utah, all Icelanders went to Spanish Fork, which by then had become the Icelandic destination. Like most of his countrymen, Loftur took land and started farming, but his main job was to build houses, but he built many not only for his countrymen but also other immigrants who settled in Spanish Fork. Loftur was gifted with leadership skills and he used them soon after arriving in the West. He was made a missionary and went on missionary missions to Iceland in 1873. With him in the west in 1857 went Jón Jónsson and his wife Anna Guðlaugsdóttir, Guðrún Jónsdóttir, Jón’s sister, as well as Magnús Bjarnason and his wife Þuríður Magnúsdóttir. Also, Guðný Erasmusdóttir, widow of Árni Hafliðason, Þórarinn’s brother. Finally, Vigdís Björnsdóttir should often be mentioned as the “Icelandic doctor and midwife” in Spanish Fork. She had gone to Copenhagen to get an education in medicine, and when she came to Utah, it was not long before her skills came in handy for pregnant women. The story goes that she birthed dozens of children in Utah, the last time she was in her eighties. In the following years, no one went west to Utah, and there did not begin westward travel from Iceland until the 1870s.

Polygamy: The founder of the Mormon Church, Joseph Smith, legalized polygamy, having multiple wives, in the church in the 1830s, and soon the church leaders adopted the practice. Between 1852 and 1890, it is estimated that up to 30% of men in the Mormon Church in Utah practiced polygamy. Church leaders took this for granted on the basis of religious freedom, but the US government opposed it and in 1862 a law was passed banning polygamy in the US territory. Utah was one of those areas where Brigham Young was the governor and leader of the Mormon Church. The law did not change anything in Utah, and the Mormons considered the first article of the US Constitution to give them the full right to practice polygamy. In 1879, the Supreme Court of the United States again ruled that polygamy was illegal, that the country’s laws were an instrument of government, and although they could not ban religion, they could ban various acts that could not be considered religious in nature. Polygamy in Utah continued, but strong opposition made all attempts by Mormon leaders extremely difficult when it came to strengthening ties with neighboring states. By 1890, it was clear that Utah could not become one of the states of the United States while polygamy prevailed, and Wilford Woodruff, President of the Mormon Church, issued a directive banning polygamy. The directive did not change the marital status of Utah polygamists, but the debate about its validity grew within the Church, leading to improved relations with the government. It was in 1896 that Utah became a state in the United States, but polygamy continued to be practiced. The new president of the Mormon Church, Joseph F. Smith, stepped in and issued a new ordinance in 1904 banning polygamy and punishing violations of these ordinances for life. Not all Mormons could agree to this, they resigned from the Mormon Church in Utah and formed new congregations that allowed polygamy. The main Mormon Church in Utah has no connection today with such a congregation and does not hesitate to expel people who violate the ban. But how do you think this went to western Icelanders?

Early Years in Utah: Circumstances surrounding the Western travels of the Icelandic Mormons were in many ways different from those of their countrymen that settled across Canada and the United States in the years 1870-1914. Icelandic Mormons were encouraged to move to Utah by fellow believers, where the Church’s blessed state awaited them, a religion that had its own laws and rules. The historian ÞÞÞ says in one place: “Although Icelanders in Utah had a hard time in many ways at first, like most of those who settle down completely among foreign nations, none of them felt harsh. And because of their new faith, which they cultivated in communion with the existing brethren, they become less foreigners than otherwise, and much quicker connected with land and people than all the bulk of the main emigrants after 1870 .. ” (SÍV II, p. 18) Furthermore, ÞÞÞ writes: “Because of their various customs, all kinds of habits and even behaviors, which at that time were not uncommon in Iceland, and their Icelandic clothing, they were considered in Spanish Fork by earlier settlers, the Icelanders are very peculiar. They were scoffed at and made fun of them in the first place. But with diligence and perseverance, they soon came to a better position. Over the years, the Utah assimilation changed their clothing and customs. There were no more ways to compare. Yet the first generation will have felt somewhat loyal to Icelandic customs, despite their new religion.” All Icelandic Mormons experienced all kinds of deceit and contempt as they embraced a new religion, throwing patriarchy on the fringes of foreign treason. With this contempt and hatred, the people moved to a foreign land in a society that at first looked at them from a different angle. But the faith of most of them was strong, and with it as a guide, the pioneers came through the early years of the settlement, “so a young religion often has more vitality than an old religion, even though in the opinion of the public it stands in many ways behind the older … Mormons live better according to their faith than we, who were raised in Lutheran Christianity. They are more sociable and helpful to each other … But it is natural and easy to understand the mentality of our Lutheran ancestors at home and in the West, which manifests itself in the hatred and contempt for their polygamy and other Mormon religious innovations, which completely violated temporal decency on this side and eternal salvation on the other side.” (SÍV II p. 19) It is quite clear that Icelandic women who went west with their husbands sometimes had a hard time when their husband married another woman, or even women, in Utah. Mormon leaders said women were essential to farmers, they were “the life and soul of Utah’s colonial farming” (SIV II, p. 19).

The hostility to the West. By the middle of the 19th century, Mormon leaders realized that no American state would welcome them and give them a place of refuge with their religion and customs. Therefore, they looked further west and established their state in an area that was later incorporated into the United States. Geographically, Utah is far from Wisconsin, Minnesota and N. Dakota, as well as in Manitoba, Canada, where Icelanders, other than Mormons, settled in 1870-1890. During this period, there was little or no contact with the Icelanders in Utah, reports of them rarely appearing in Western Icelandic newspapers in Minnesota or Winnipeg, let alone reciprocal visits. It was not like the Icelandic Mormons severed all ties with their country and nation, and those who went west did not want to know that some of their countrymen had settled in Utah. A good example of the agitation by “northerners”, as the Mormons sometimes called their countrymen in the aforementioned states and provinces was the experiment of Icelandic missionaries who visited their countrymen in N. Dakota and Manitoba. Reverend Friðrik J. Bergmann wrote about this in the Almanak in 1903 and says: “In the summer of 1879, Icelandic Mormon missionaries were on the move and had great agitation both down in New Iceland and in Winnipeg. This summer, “Framfari” includes articles on the Mormon mistake. Rev, Jón Bjarnason was then challenged by someone to speak publicly against them. But he sees no reason to do so, and says he will not do so unless Christian wisdom dictates it him. It did not go unnoticed that there were those in Winnipeg who were more inclined to their doctrine, though they would not make much progress. But it can be said in praise of the Winnipeg Icelanders that they usually resisted their false doctrine, so the missionaries had to move on. In New Iceland, people agreed not to allow them to preach in their homes and not to listen to their case. There were committees about this in both the congregations of Rev, Jón Bjarnason and Rev. Páll Þorláksson, and in Winnipeg they were harassed, so they could not keep up and nothing was done. In addition to the fact that the Winnipeg Icelanders were anxious to deter their countrymen from making such a mistake, they knew that it would be to the detriment of our entire nation in the eyes of the people, if it came to light, that the Mormon error had many fans among them. ”

Einar Hermann Jónsson Photo: Almanak 1916

Icelandic patriotism: This deep hatred of the Mormons in the various Icelandic settlements of the West, of course, meant that little or nothing was done together to strengthen the Icelandic heritage in the West. The first generation of Icelandic Mormons tried their best to preserve the language as well as various folk customs; they taught their children the language, history and culture. A meetinghouse was built early on in Spanish Fork and Icelandic meetings were held there, and which held Icelanders’ Day on August 2, annually from 1897 to 1903. Around the same time a reading society was founded that lived longer and owned about two hundred books at its peak, but in 1915 there were few members and the society was poor. Undoubtedly, writers, even poets, have been among the Icelandic Mormons who moved to Utah, but what should the material be and for whom is it written? It was stated above that Einar Hermann Jónsson (E. H. Johnson in Utah) had written a kind of history of the settlement of Icelanders in Utah and it was published in the Almanak in 1915. Shortly after it was published, his writings began to be criticized, most notably for his opinions when discussing Icelandic settlers and their families. At one point in his book, ÞÞÞ says this when he has presented Einar’s work: “These are the best sources about of the Utah settlers that I have at the time of writing (February 1940). It does not say that these were families, because the work almost never mentions that women moved to Utah, but lonely men. Nor are there any children mentioned as a rule, neither those born in Iceland nor the West. However, the wives of these men are mentioned and where they come from, but it can never be said at least on which side of the ocean they were married, or where they came from in Utah.” (SÍV I, p. 113) Elsewhere he says: “It is also worth mentioning that in Utah history, Einar H. Johnson omits all women who in the old days of Utah married the men who were married before, although it does not bother him to mention the names of the Polygamists who married these women, and considers them good and valid fellow citizens and brothers”. He quotes an article in a letter and says: “A woman who had lived in Utah for a long time wrote to me that she had known about 30 Icelanders – most of them women – who had lived in Spanish Fork for a longer or shorter period of time, whom Einar omitted from his Settlement History. She mentioned this “accident” to him, but he did not find it wrong to omit people who had “lost themselves” and said he “did not make it a habit to write a book about dishonest women.” But then he named the wives of the polygamous men.” (SÍV II p. 16).

English version by Thor group.