State of Wisconsin: Wisconsin is in north-central USA, with Minnesota and Iowa to the west, Illinois to the south, Lake Superior and the state of Michigan to the north, and Lake Michigan to the east. The area is warm, moist, and sunny in the summer, but cold and snowy in the winter, although not as cold as Canada to the north. Granites and similar rocks underlie the forested northern portion of the state, although sandstone and limestone underlie the productive agricultural lands of southern Wisconsin, which are now famous for dairy. Icelandic settlement principally occurred in the good farmland of east-central Wisconsin, in the areas of Shawano, Dane, and Door Counties, including Washington Island in Lake Michigan. H. Thorleifson

Wisconsin became s state in 1848. The name comes from the Algonquian language of the Indian nation that lived in what was later Wisconsin when European explorers first passed through. The Frenchman Jacques Marquette (1673) was the first to reach the Wisconsin River and named the river Meskousing in his diary. His countrymen changed the spelling and wrote Ouisconsin and it was long used both as the name of the river and the area from its banks. In the early 19th century, as British explorers and settlers flocked to the area, the spelling changed to Wisconsin. The meaning of the original word is lost, but one theory says that it is the same word as Meskonsing, which means “reddish”, and refers to the reddish sandstone where Wisconsin flows in one place. Other explanations suggest that the word came from the Ojibwa language of the Indian nation, which means “place of red stones”.

Settlement Begins: West of Wisconsin are Minnesota and Iowa, Illinois to the south, Lake Michigan to the east and Michigan to the northeast. Lake Superior is on the north side. The capital is Madison, and Milwaukee is the largest city. French explorers came from the north, the French territory in eastern Canada. Their route was through the Great Lakes and many came ashore where Green Bay is now. Their main interest was the fur trade, and the same can be said of the British who took control of Wisconsin in 1783. French fur traders, however, settled there, preferring to move north across the border to Canada, where the British had all the power. The land from Green Bay was gradually organized and fur traders, French and British, settled there. From 1763 to 1780 the community was flourishing and peaceful. Wisconsin became American land in 1783, but the British ruled it until 1812, when they lost power after the war. The Americans soon disappeared from the fur trade and turned to mining. Immigrants’ interest in opportunities in Wisconsin grew, and immigrants flocked to the area from Europe as well as from various states in the United States. This rapid growth of white immigrants led to wars with Native American nations, with two wars, one in 1827 and the other in 1832, leading to the expulsion of indigenous people from Wisconsin who were driven west. Subsequently, by law on April 20, 1836, the United States Congress declared Wisconsin to be a U.S. territory. As early as that fall, many New England farmers had settled in thriving rural areas around Milwaukee. Villages and towns saw the light of day and around the same time many Germans and Norwegians came to Wisconsin. In the years 1840-1850, the population grew from over 30,000 to over 300,000. It was on May 29, 1848, that Wisconsin became a state in the United States.

Settlement Begins: West of Wisconsin are Minnesota and Iowa, Illinois to the south, Lake Michigan to the east and Michigan to the northeast. Lake Superior is on the north side. The capital is Madison, and Milwaukee is the largest city. French explorers came from the north, the French territory in eastern Canada. Their route was through the Great Lakes and many came ashore where Green Bay is now. Their main interest was the fur trade, and the same can be said of the British who took control of Wisconsin in 1783. French fur traders, however, settled there, preferring to move north across the border to Canada, where the British had all the power. The land from Green Bay was gradually organized and fur traders, French and British, settled there. From 1763 to 1780 the community was flourishing and peaceful. Wisconsin became American land in 1783, but the British ruled it until 1812, when they lost power after the war. The Americans soon disappeared from the fur trade and turned to mining. Immigrants’ interest in opportunities in Wisconsin grew, and immigrants flocked to the area from Europe as well as from various states in the United States. This rapid growth of white immigrants led to wars with Native American nations, with two wars, one in 1827 and the other in 1832, leading to the expulsion of indigenous people from Wisconsin who were driven west. Subsequently, by law on April 20, 1836, the United States Congress declared Wisconsin to be a U.S. territory. As early as that fall, many New England farmers had settled in thriving rural areas around Milwaukee. Villages and towns saw the light of day and around the same time many Germans and Norwegians came to Wisconsin. In the years 1840-1850, the population grew from over 30,000 to over 300,000. It was on May 29, 1848, that Wisconsin became a state in the United States.

Danes and Icelanders: By the middle of the 19th century, many Danes had converted to Mormonism and moved to Utah in the United States. There was a lot of discussion about emigration in Denmark at that time, and there were also speculations in Iceland about emigration. In 1860, about 1,100 Danes settled in Wisconsin, and there are various explanations for this. The state offered immigrants various benefits, e.g. that the climate and soil were particularly suitable for farmers who wanted to raise livestock and run dairy farms. Such farming was suitable for Danish farmers who followed suit and they spread somewhat throughout the state. Reports of this reached Iceland and were naturally discussed. A Danish shop assistant, Wilhelm Wickmann, worked in Eyrarbakki, but his sister had just moved to Wisconsin and was married to the Danish consul in Milwaukee. The story goes that she wrote to her brother and encouraged him to move west to her which he did in the autumn of 1865. Wilhelm corresponded with Guðmundur Thorgrímsen, a merchant in Eyrarbakki, and described local conditions in Wisconsin and considered various advantages of the state, e.g. fishing in Lake Michigan. His descriptions hardly mention the achievements of his countrymen in Wisconsin, but the number of Danes had risen to several thousand by 1870 (8,797 in the 1880 census). The popularity of the Danes in Iceland around 1870 was not great and some success stories of them in Wisconsin as well as their number, might have slowed down the first Icelandic Westerners to let go of their claws in Iceland and then rush to plant their feet in Wisconsin. The first Icelanders to move west to Wisconsin were Jón Gíslason, Guðmundur Guðmundsson, Árni Guðmundsson and Jón Einarsson. They got to know Wilhelm’s descriptions in the letters to Guðmundur in Eyrarbakki and they mostly decided on the decision to go west. He and Jón Gíslason would have discussed the possibility of some kind of collaboration when Jón came to the west. The foursome went west in 1870, spent the summer in Milwaukee, but moved to Washington Island in the fall (see more about them there). None of them sought refuge with Danish immigrants, and the same can be said of the next Icelandic immigrants who went to Wisconsin in the years 1870-1873.

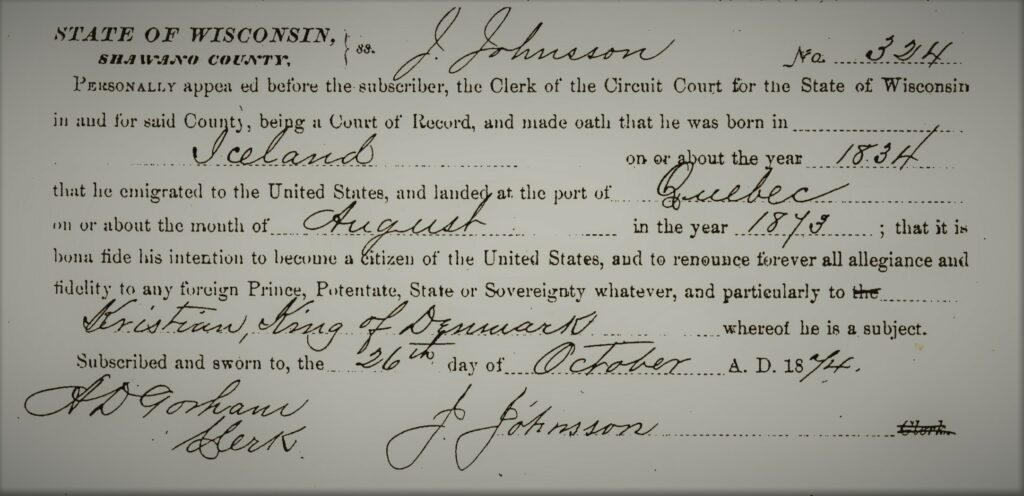

Certificate of Citizenship. Here is an example of a US citizen letter that immigrants filled out conscientiously in a public institution. This is how Jón Jónsson, the father-in-law of Stefan G. Stephansson, went in October 1874. The document clearly states that Jón renounces all ties with other countries, presidents or kings, especially Kristján, King of Denmark. No doubt it has not been difficult for him.

Norwegians: The period of emigration begins in 1825 in Norway and therefore Norwegians had a much longer history in the West than other Nordic people. They divide their history in the West into three periods: 1825-1860 is the Norwegian period, 1860-1890 they call the Norwegian-American period, and 1890-1925 is the American period. At first, Norwegians emphasized their own language and Norwegian values. In the next period, they will be as much American as Norwegian. They spoke as much English as Norwegian, watched events in the United States and Norway with equal vigor, waved both the American and Norwegian flags, and celebrated the Norwegian National Day on May 17 and the American Independence Day on July 4. The latter period is characterized by American values, Norwegian customs almost disappearing. English is spoken both in Norwegian homes and in American-Norwegian society, pastors hold services in English and Norwegian traditions rarely mentioned, the generation is born and raised in the United States. The Icelanders in Wisconsin met Norwegian settlers during the Norwegian-American period, and some thought that their Norwegian cousins had grown quite a bit away from Norwegian values originating in Norway. Others were obviously impressed by the success of the western Norwegians and considered their path to a better life in a foreign country was to be emulated. The best example is Páll Þorláksson (see him) who went west in 1872. He took the time to get to know Norwegian settlers, in fact, he had a Norwegian connection because his maternal grandfather was Norwegian. Norwegian pastors took Páll to the various Norwegian settlements and he was fascinated by what he saw. He wrote a letter to the editor of Norðanfari on January 23, 1873, which was published in the paper. There, Páll says “It is remarkable that in the last 30 years of migration from Norway (on a large scale), Norway seems to be as right as before, and Norwegians here will soon be as numerous in the United States as in Norway itself. In this short time, the Norwegians in the states have done an incredible amount. They have gradually come together, formed congregations, built churches and primary schools, formed denominations and a Latin school called “Luther College”, and it cost the Norwegian congregation 87,000 dollars. They themselves paid all the costs …. It is best for those who come here, especially Icelanders, not to start gambling on their own right away, but to learn as much as possible at the beginning of what is useful .. “.

Norwegian assistance: Páll’s message to his countrymen in Iceland was clear: he encourages everyone to get acquainted with new and unfamiliar work methods. Páll did not stop there, he prepared for the arrival of his countrymen to Wisconsin by negotiating with Norwegian farmers to keep new Icelanders with them for some time so that they could learn new ways of working and more necessary in the West. Let’s look at what he says about this in another letter to Norðanfari on October 18, 1873, when 135 Icelanders had come west to Wisconsin. There he says that he accompanied some families out to the country and says: ”When we got there, we were greeted with enthusiasm by the Norwegians, who told us that their pastor had asked them from the pulpit, to welcome the Icelanders if they could. Farmers came and picked up their Icelandic families … Although I really like the choice of these Norwegian people that these countrymen came to …. I do not think that they hope they like everything or like each other, right away while they are strangers and do not fully understand the language. More Icelandic families have gone to the Norwegian congregation and some freemen, but so far I have heard almost nothing from them. I think I know that they are doing better in the country than if they had settled in the cities e.g. Milwaukee. Now a pastor from Wisconsin (Páll was in St. Louis) writes to me that the three families in his congregation are doing well.” A year later, many Icelanders settled in a small, Icelandic colony in Shawano County in northern Wisconsin, but some continued to work for Norwegian farmers and later moved west to Minnesota.

English version by Thor group.