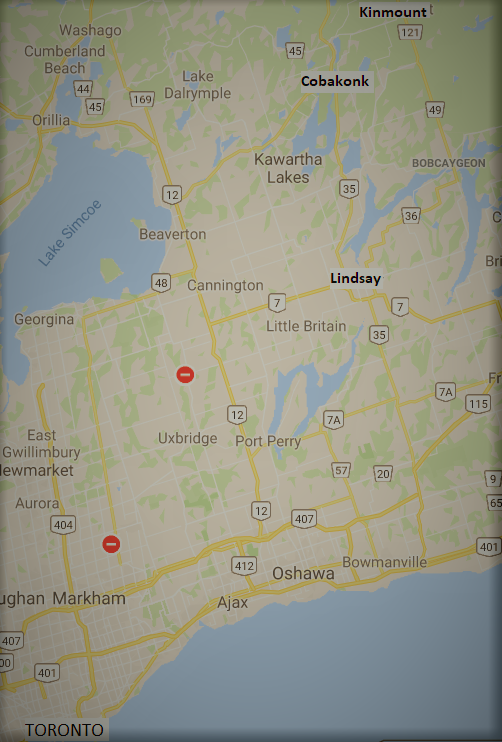

Kinmount is a small town about 163 km (80 miles) northeast of Toronto and the village was originally named Burnt River after the river that flows through it. In 1859 the village was named Kinmount after a place of the same name in Scotland. British influence in Ontario grew steadily after 1860, relying primarily on a steady stream of immigrants from the British Isles. When the North American crisis hit around 1872, it was followed by massive unemployment, which led to declining interest in western immigration in the British Isles. The flow of immigrants to Ontario had been steady, bringing with it a much-needed workforce in a growing transportation system, industry of all kinds, logging, and mining. The young nation of Canada strived to establish a settlement in its west, and gradually settlements in the southern part of the province became denser, so the government began to encourage settlement further north. The promotion went slowly up to 1870 as there was a shortage of building materials in the south of the county but there was plenty in the north and to transport it to the south needed railways. Logging thus accelerated settlement, land was cleared and taken. The land around Kinmount was forested, but there was no railroad. In 1874 there was a plan to build a railway there in the autumn.

Kinmount is a small town about 163 km (80 miles) northeast of Toronto and the village was originally named Burnt River after the river that flows through it. In 1859 the village was named Kinmount after a place of the same name in Scotland. British influence in Ontario grew steadily after 1860, relying primarily on a steady stream of immigrants from the British Isles. When the North American crisis hit around 1872, it was followed by massive unemployment, which led to declining interest in western immigration in the British Isles. The flow of immigrants to Ontario had been steady, bringing with it a much-needed workforce in a growing transportation system, industry of all kinds, logging, and mining. The young nation of Canada strived to establish a settlement in its west, and gradually settlements in the southern part of the province became denser, so the government began to encourage settlement further north. The promotion went slowly up to 1870 as there was a shortage of building materials in the south of the county but there was plenty in the north and to transport it to the south needed railways. Logging thus accelerated settlement, land was cleared and taken. The land around Kinmount was forested, but there was no railroad. In 1874 there was a plan to build a railway there in the autumn.

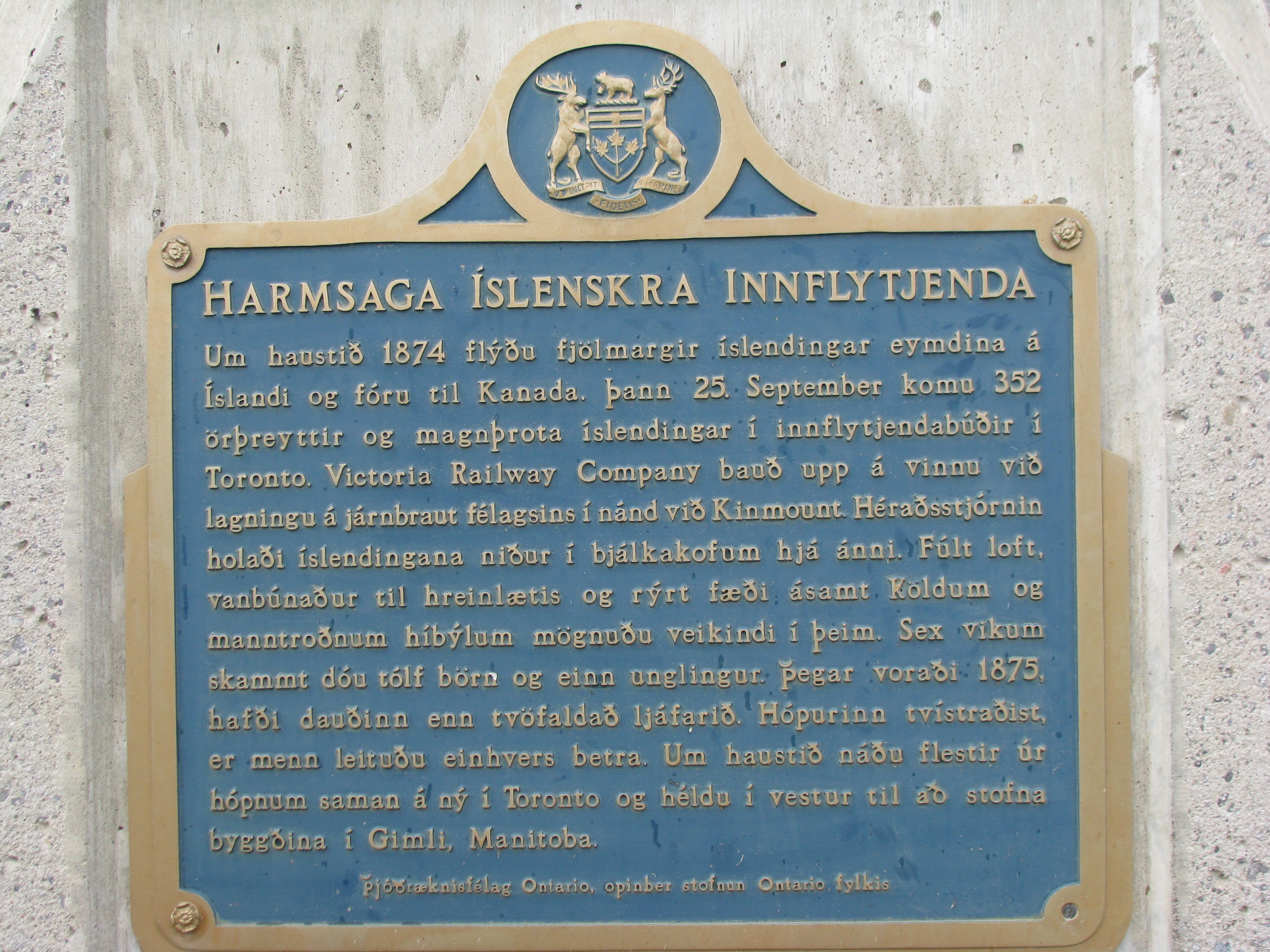

Icelandic labor: Sigtryggur Jónasson followed the western travels of his countrymen, knew that many went through Canada south to Wisconsin where Páll Þorláksson prepared for their arrival there and brought them to stay with Norwegian settlers there. Sigtryggur also knew that the minds of most western Icelanders were set on forming an Icelandic settlement in North America. He had lived in Ontario since 1872 and had studied many aspects of immigration. He knew the government’s emphasis on areas for future settlement of immigrants such as e.g. Muskoka. His countrymen had gone there in the late summer of 1873 and were settled in the Cardwell district northeast of the village of Rosseau. He made his way there in the spring of 1874, he knew of a large group expected from Iceland in the summer and was looking for a respectable area for settlement. He looked around in Muskoka but did not find what he was looking for. He seems to have made the decision after the excursion to Muskoka to follow Páll Þorláksson’s example in Wisconsin to get supplies from farmers in Ontario so that Icelandic immigrants expected in the summer could learn new ways of working and better prepare for their own settlement. In a letter written by him from Kinmount on October 13, 1874, he states: “The initial plan was, if they had arrived in time or during the harvest season, to provide them with supplies from the farmers and let them get acquainted with their customs before they started farming themselves.” But Allan Shipping Company delayed the group significantly, arriving in Quebec on September 23 and arriving in Toronto two days later. Sigtryggur Jónasson was an immigration agent of the province of Ontario and an interpreter. He received the group in Quebec and accompanied them to an immigrant camp in Toronto. On the way there, it was discovered that many people had suffered from severe gastritis and some had suffered significantly at sea. The stay in Toronto refreshed some, but there was uncertainty about the future. It can be said that it was a serious misfortune that the railway company that was supposed to build a railway from the town of Lindsay to Kinmount was in big trouble due to a lack of labor. It had been the practice to hire farmers for such work, it was considered an benefit if they lived close to the workplace. But farmers did not rush this time because the harvest season was not over. This lack of workers came to the attention of the Ontario Provincial Department of Immigration, who then no doubt pointed Sigtrygg to the railway company and who was well received there. The company agreed to hire Icelanders to work on the railway construction, it decided to build a cabin in Kinmount where workers would live. While working on the Kinmount buildings, the immigrants in Toronto waited. Here it is important to pause in the narrative and ponder a terrible misunderstanding. The railway company was hiring men over the winter, but the Icelanders prepared families, women, children and the elderly for the trip to Kinmount. The huts that were built there were log houses and they are described as follows: “These huts were made of rough trees and spaces were filled with moss and clay. The roofs were made of boards (reisifjalir) and the floor was made of planks. First, four huts were built. Two 70 feet long and 20 feet wide but the other two were shorter by half with the same width. But when the Icelanders moved there, the huts turned out to be both small and too few. At that time two more huts were built the size of the smaller ones: 35 feet long and 20 feet wide, and there was a ceiling in one of them. Ceilings were also installed in both larger houses.” (SÍV2-p. 285)

The picture shows a typical forest near Kinmount. The Icelanders who worked for the railway company worked in such a landscape. They had to cut down trees, blow up rocks, fill depressions and ditches. Photo JÞ

Natural circumstances: Sigtryggur Jónasson does not seem to have realized that the railway company had built the huts for workers, men who lived together while working on the railway construction between Kinmount and Lindsay. He describes the families’ journey from Toronto to Kinmount in a letter to Norðanfari from Kinmount, dated February 1, 1875, stating: “The distance from Toronto to Kinmount, is 102 English miles, and goes 88 miles northeast by the Toronto and Nippising Railroad to a town, which lies at the end of this track and is called Cobakonk. From there it is 14 miles to Kinmount, which must be reached by horse-drawn wagon. To get to Kinmount, the same day, we had to leave Toronto at 8 in the morning, and we arrived in Cobakonk a little after noon. Everyone had lunch there, and after that the women and kids and the most necessary of the luggage were loaded on the horse-drawn carriages, which had been requested in advance and brought there. Everything had gone well with the countrymen so far, except that they were not the most comfortable when they traveled by steam power in Quebec for the first time. But when it came to the horse-drawn wagons, the journey began to look darker. All healthy men were expected to walk these 14 miles, while the rest rode. But the healthy had to get in the wagons and rest, so time was wasted, as again the wagons had to be stopped and men got down, and the wagons filled again with kids and women. It was so dark when we started, so much of the jouney had to go in the dark, which was rather unpleasant, as it was rough and wet from the rain.” Símon Símonarson from Breiðstaðir in Sauðárhreppur was in this group with his wife and two children and ÞÞÞ uses a chapter from Símon’s biography (SÍV2 pps. 286-7): “Símon Símonarson is shocked by the journey from Cobakonk to Kinmount. He says that when he finally reached the end of the journey, after the men had walked about 14 miles over rocks and brush and mud, and the women and the poor children were almost shaken apart on the bad roads and clumsy wagons, the people had been huddled down out of the wagons, hungry and sick, at about twelve o’clock at night in the pitch-black darkness, in the middle of a forest, and had no idea where to go. Finally after the long struggle, when the immigrants were soaking wet, two countrymen came to them with a lantern and described them to the “huts” that were being built, and some Icelanders worked on them.” ”In this miserable home, some food was served, but only the healthiest and those who cared for themselves enjoyed it, but the lazy and sick did not recover. ”

Immigrants’ problems: The conditions in the huts were poor, the people crowded together, the huts were smelly and airless. Children’s illness was severe, with some sources saying that all children within the age of two years died there in Kinmount. Simon wrote in the autobiography that “.. in Kinmount almost 30 children and some of the adults (almost 10), mostly old men, have died.” He himself looked after his two-year-old daughter, Guðrún. He describes the horrific suffering of the child who died on the evening of October 10. His friend, Jón Ívarsson, made the coffin and he and Jón Espólín carried little Guðrún to the grave in the Kinmount cemetery. Each hut had a stove, and the railway company originally intended a resident to cook one meal a day for all residents of each hut. The residents were supposed to take care of the cooking, but this arrangement was not suitable for Icelandic families, every housewife wanted to cook for herself and her family. The tension hit all the residents hard and made the cohabitation extremely difficult. The men who worked for the railway company worked during the day and were paid more than a dollar until the end of the year, but in the new year wages were reduced to 90 cents. Some people were forced to look for work elsewhere, the railway company did not need all the able-bodied people. Some were employed by nearby farmers, others in nearby villages and towns. Sigtryggur Jónasson work hard to help the people with their lives. He spread out to open a store for his countrymen, but many thought his prices were higher than in nearby markets. He took on Friðjón Friðriksson as a partner with him and he took care of the shopping and delivery. Sigtryggur tried hard to make their stay in Kinmount tolerable, he provided young girls with work in homes in towns such as Lindsay and took over teaching at the school, which began in March, 1875. In March came the final blow, work on the railway was stopped due to lack of funds. The Icelanders were suddenly unemployed and did not have many benefits. Some signed up for land and started clearing, others sought out farmers and nearby settlements. Although the people of Kinmount soldiered on, they gradually realized that the land in Victoria County, Ontario, did not offer what had led them westward across the ocean. Here the dream of an Icelandic colony could not come true.

English version by Thor Group.