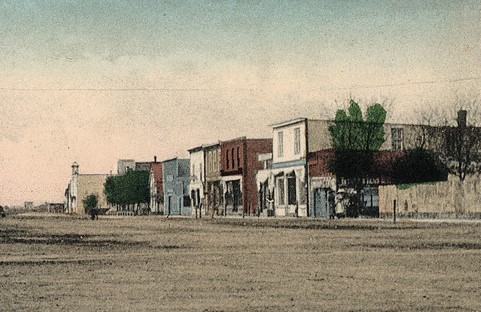

The earliest records of explorers’ travels through the area where the town of Glenboro stands in Manitoba tell of one David Thompson’s journey across the plain in 1798. He noted that the soil there seemed exceptionally fertile. However, it was Jonas Christie and James Duncan (British immigrants) who first settled there in 1879, and when the Settlement Act came into force in Canada in 1880, the number of settlers soon increased. The Canadian Railway Association (CPR) worked quickly and efficiently to build a railroad across Canada from Toronto, west to Winnipeg, and from there west along the plains. In 1882, it was clear that the track was heading west through the lands of Christie and Duncan, so they seized the opportunity and offered the company land for a village. During these years, locomotives had to be serviced at certain intervals, and large water tanks were built at those train stations. Then a village arose. The lands around these villages developed rapidly and were valuable because farmers did not have to travel long distances to bring their produce to market. The Canadian government surveyed the land and invited settlers. A railway was a result and there are many examples of Icelandic settlers getting on a train in Winnipeg and taking it west to the plains, sometimes they got off in some Icelandic settlement but sometimes they took a train as far west as they could. This was especially common when land was opened up into what is now Saskatchewan. The railway company accepted Christie and Duncan’s offer and a railway station was built in 1886 where Glenboro is now.

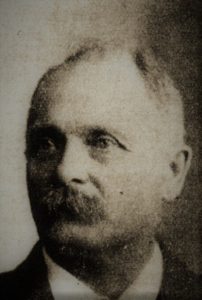

Friðjón Friðriksson

Icelanders settled: Friðjón Friðriksson took the train from Winnipeg to Glenboro in the autumn of 1886. He was born on Melrakkaslétta in 1849 and came west to Ontario, Canada in 1873. Sigtryggur Jónasson was there and he hired Friðjón to run his small store in Kinmount in early January 1875. They continued the collaboration in Gimli in New Iceland for the years 1875-1880 and Friðrik went on trade expeditions north of Lake Winnipeg and gained valuable experience. When the emigration from New Iceland was at its peak in 1879-1881, Friðrik lived in various places, e.g. by the Icelandic River, in Selkirk, and in Winnipeg.

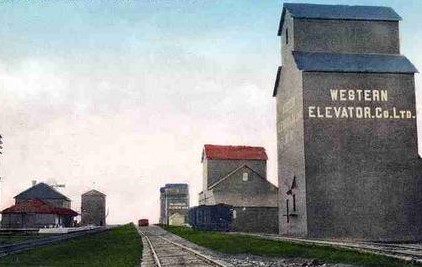

Here you can see the railway that was built in 1886 and the railway station. Then there are grain elevators that can be seen across the entire plains.

Friðjón’s heyday in the West began with his move to Glenboro. His shop immediately became popular, Icelanders in the Argyle Settlement came to him from all over and from nearby settlements. He recruited his countrymen, Halldór Bjarnason from Dalasýsla who came west in 1887 and came to Glenboro a year later. He worked in Friðjón’s store for 12 years. Sveinn Björnsson from Brunnastaðir on Vatnsleysuströnd came west to Canada in 1887 and later settled in Glenboro. He opened and ran a blacksmith workshop in the town in 1888, was the first Icelandic blacksmith in the village. He sold the workshop to Jón Gíslason (Gillis) from Árnessýsla in 1896 and Jón managed it until 1932. Ólafur Jónsson (registered as Ólafur J. Ólafsson in the west) from Húnavatnssýsla came to Glenboro in 1898 and managed a harness store for some time. Loftur Guðnason from Rangárvallarsýsla settled in Glenboro in 1898 and worked in watchmaking and goldsmithing for two years (died in 1900) and Guðmundur Lambertsen came to town in 1911 and ran a goldsmith and ornamental shop until his death (1947). Icelandic immigrants in the village were involved in various service jobs, such as mail transport, care and cleaning of public buildings and schools, and domestic help. They were always involved in public affairs, sitting on local councils, schools and town councils.

Social activities: Those who settled in Glenboro early on followed the example of their countrymen in Icelandic settlements in Canada and the United States. It was immediately clear to them some kind of social activity for Icelanders was necessary for the maintenance of the Icelandic heritage. There was no longer any discussion of exclusive Icelandic settlements in Canada or the United States, it was clear to everyone that each ethnic group was a rich factor in shaping a new society. Icelanders now sat on committees and councils in their settlements and towns with men and women of different origins. This fact led Icelanders to want their own associations, churches and congregations. A reading society was founded in early Glenboro and flourished for a long time. A women’s association was founded early and worked long and hard, but around and after the turn of the century it struggled and came to an end. Another women’s association was founded on April 29, 1914 and has done a lot of work. In particular, it worked diligently to bring in well-known Icelanders, lectures, singing, etc.