Solomon Juneau statue in Milwaukee, WI

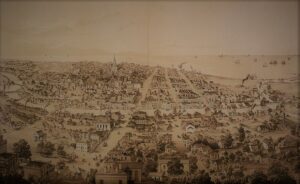

Milwaukee is the largest city in the state of Wisconsin. It was built on the west shore of Lake Michigan in the middle of the 19th century, but for centuries indigenous peoples had traveled through the lakes and rivers of the district. The name of the city is from the Algonquian language (synonymous with by far the most populous nation of Native Americans in North America. This great nation branched out into smaller ones such as Menominee, Sauk, Potawatomi and Ojibwe) and means good country or beautiful and comfortable country. Indigenous peoples lived in the area around Green Bay but searched south along the west shore of Lake Michigan in the early 19th century. Wars between them and immigrants were frequent and led to wars with the US military. Indigenous peoples feared the expansion of the United States, and to stop it, they attacked Chicago on August 15, 1812. It was unsuccessful because the Americans were convinced that the only way for their Western expansionist policy to succeed was to expel indigenous peoples from their lands. In 1833, the Indigenous peoples agreed to a treaty in Chicago (Treaty of Chicago) and with it they agreed to leave all their lands and move west across the Mississippi River (Indian Treaty). Explorers and missionaries searched west of Lake Michigan in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. In 1785, Alexis Laframboise set up a fur trade in the area where the city was later built, but the first to settle there was the Frenchman Solomon Juneau in 1818 and the village that was built there was normally named after him and called “Juneau’s town”. In 1846, on January 31, it was merged with two other villages and the city of Milwaukee was formed.

Nordic center: Norwegian immigrants were the first Nordic people to settle in Wisconsin. In 1838, a few of them moved west, but they had come west to America a few years earlier. They settled in Rock County, in the south of the state. In the summer of 1840, a group of 60 men set out from Stavanger, Norway, and arrived in Rochester, New York, a few weeks later. From there, the road led to Buffalo and then along the Great Lakes to Milwaukee. The group headed south to La Salle County, Illinois, but entrepreneurs in the town pointed to a severe malaria epidemic in the area and adverse weather conditions, which were considered stormy. The Norwegians settled in Muskego, Milwaukee County, just south of Milwaukee. A few later returned to the city and became entrepreneurs there. (HNPiA p. 160) In 1870, more than 5,000 Danes settled in Wisconsin, most of them in various counties where they farmed. Many of them opted for business and settled in Milwaukee. This number of Danes in the state in the years 1860-1870 led to the appointment of a Danish consul and the married sister Wilhelm Wickmann, a former shop assistant at Guðmundur Thorgrímsen in Eyrarbakki. There also worked a Danish man, Keyser by name, and he moved to Milwaukee, where he helped some of the Icelanders who immigrated there from 1870. In a letter dated September 8, 1872, the correspondent, Jón Halldórsson from Stóruvellir in Bárðardalur, says this is about the Danish consul and Keyser: “The consul advised us not to go to the island (Washington), because we had nothing to do there, he advised us to cross the lake here, and work in a sawmill, 9 of our countrymen had gone there three days ago …. We visited Keyser, who has rented a house here in town; he has works at cleaning wagons and gets one and a half dollars for it a day. He did not like Wickmann’s business and said that our countrymen had suffered with their association with him.. ” Jón’s friends in Milwaukee were Jónas Jónsson from Stóruvellir and Jóhannes Arngrímsson from Nes in Höfðahverfi. A bank collapse in 1872 in the United States led to massive unemployment across the continent. The situation had not improved by late 1873, when 135 Icelanders had moved to Milwaukee, most directly from Iceland and a few from Ontario in Canada. The winter that was approaching was difficult for all of them due to unemployment, but it generated a lot of discussion about the formation of an Icelandic colony in North America. In 1870, the city had a population of over 70,000 and German immigrants were the most numerous. The number of Norwegian and Danish immigrants increased in the city in the last decades of the 19th century, but the number of Icelanders decreased. The city was, however, the center of Icelanders at the beginning of the Migration Period, becoming a kind of significant stepping stone for Icelanders in North America in the years 1870-1875. Two things caused a turning point from 1875, on the one hand the settlement in Minnesota and the establishment of a new Icelandic colony there and on the other hand New Iceland in Canada. The year 1874 was not only significant in the history of the Icelandic nation at home in Frón (Iceland), events in Milwaukee this year were to have a great impact on the lives of Icelandic immigrants in North America.

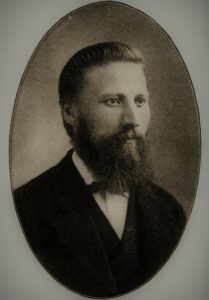

Rev. Jón Bjarnason in Milwaukee in 1874. Photo: Minningarit

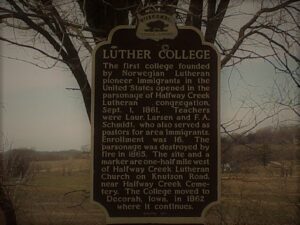

Icelandic social spirit: Two men came west to Milwaukee, Wisconsin in the fall of 1873. One of them was Jón Ólafsson, a Member of Parliament, editor and poet who may have fled Iceland because of his views on the Danish government and its representatives in Iceland, and the other was Rev. Jón Bjarnason. He was very dissatisfied with the Latin school in Iceland and the teaching methods there, as well as the Icelandic national church, which he criticized extensively. This criticism of his no doubt contributed to the fact that he was twice refused when he applied for a congregation in Iceland. The priest knew Páll Þorláksson from his years of study in Reykjavík, but he was a cousin of Lára Guðjohnsen, Reverend Jón’s wife. Páll had corresponded with Reverend Jón, described to him the Norwegian congregations and their higher schools. He did not consider it unlikely that Reverend Jón would be offered a priesthood in the Norwegian Church. The two icons had in common that they were forced to move west, neither of them intended to start farming, but the future of both in the West was largely dependent on their fellow countrymen who had come to the west and no less on those who came later. Reverend Jón went straight to a meeting with Páll in St. Louis, Missouri  where he was studying theology. The Norwegian Synod sent its pastorate to the school of the Missouri German Church in St. Louis, which was the most powerful Lutheran denomination in North America at the time, but also the most narrow-minded. Páll had indicated in a letter to Reverend Jón that he would probably have to attend some time in this seminary before he could get a position with the Norwegian church. Nothing came of that schooling, but the Norwegian Church offered Rev. Jón a teaching position at the Society’s Latin School in Decorah, Iowa, and Rev. Jón accepted it. Once there, Reverend Jón made an effort to get to know the activities of the Norwegian Church as well as the congregation’s work. This is stated in the publication ÞÞÞ, Saga Íslendingar í Vesturheimi ll p. 154-155: “Little by little, a new world began to open up for Reverend Jón. Everywhere he looked, there was a lively, active church life, with a strong interest, strong opinions and extensive social work. This was the free church, independent of the state. This new world aroused his astonishment and admiration.” However, his interest in the Norwegian Church and his fascination with vigorous congregational work gradually changed as he read more about the church’s message and doctrines, as well as in discussions with Norwegian priests. He thought that their conservatism in important matters was excessive, e.g., they defended slavery in the United States, claiming that unbaptized children and Gentiles would perish forever, even though they had never had the opportunity to hear the word of God. The winter wore on, and it was clear to both him and the leaders of the Norwegian Church that the difference of opinion was too great for him to serve as a parish priest. However, he was considered an excellent teacher, so he was offered the position at the school. He describes this in a letter to Helgi Hálfdánarson, dated May 5, 1874, in Decorah: This offer I have decided to accept but only for one year because of the priest’s spiritual approach on almost everything and I dislike it as much as before because of their lack of freedom and fanatic opinions on almost everything. If my countrymen here in the west have come so far that a priest can make a living by serving them, then I will probably serve them; but if it does not, then I will probably disappear from here, for a priest in this synod I have long ago resolved never to be, and that even though they may relax their views, and it is my firm conviction that Icelanders, who here west move, beware of joining this denomination. Páll Þorláksson has a completely different opinion on this than I do, because he appreciates so well the old Lutheran interpretation of the literal rhetoric by the Norwegian clergy.” It’s worth pausing here and consider the words of the pastor. He writes off the Norwegian Church as a future career, even warning his countrymen not to connect with it in any way. With these words it can be said that he is declaring war on his friend Páll Þorláksson, but at the time the aforementioned letter was written, Páll was finishing his theology studies at this same Norwegian church with the intention of becoming one of its pastors. It is also noteworthy that in his words there is perhaps the hope that the Icelandic colony in North America will become a reality and then he will become a pastor there. It also came to light that he was a staunch supporter of the ideal that Icelanders should settle somewhere remote, preferably outside North American societies where the Icelandic heritage could be preserved and the Icelandic language preserved for the foreseeable future. In the conclusion of the letter to Helgi Hálfdánarson, Reverend Jón says: “Jón Ólafsson is doing well here, and he has written a bit here in a Norwegian newspaper about Iceland.” What was Jón Ólafsson he thinking about in the spring of 1874?

where he was studying theology. The Norwegian Synod sent its pastorate to the school of the Missouri German Church in St. Louis, which was the most powerful Lutheran denomination in North America at the time, but also the most narrow-minded. Páll had indicated in a letter to Reverend Jón that he would probably have to attend some time in this seminary before he could get a position with the Norwegian church. Nothing came of that schooling, but the Norwegian Church offered Rev. Jón a teaching position at the Society’s Latin School in Decorah, Iowa, and Rev. Jón accepted it. Once there, Reverend Jón made an effort to get to know the activities of the Norwegian Church as well as the congregation’s work. This is stated in the publication ÞÞÞ, Saga Íslendingar í Vesturheimi ll p. 154-155: “Little by little, a new world began to open up for Reverend Jón. Everywhere he looked, there was a lively, active church life, with a strong interest, strong opinions and extensive social work. This was the free church, independent of the state. This new world aroused his astonishment and admiration.” However, his interest in the Norwegian Church and his fascination with vigorous congregational work gradually changed as he read more about the church’s message and doctrines, as well as in discussions with Norwegian priests. He thought that their conservatism in important matters was excessive, e.g., they defended slavery in the United States, claiming that unbaptized children and Gentiles would perish forever, even though they had never had the opportunity to hear the word of God. The winter wore on, and it was clear to both him and the leaders of the Norwegian Church that the difference of opinion was too great for him to serve as a parish priest. However, he was considered an excellent teacher, so he was offered the position at the school. He describes this in a letter to Helgi Hálfdánarson, dated May 5, 1874, in Decorah: This offer I have decided to accept but only for one year because of the priest’s spiritual approach on almost everything and I dislike it as much as before because of their lack of freedom and fanatic opinions on almost everything. If my countrymen here in the west have come so far that a priest can make a living by serving them, then I will probably serve them; but if it does not, then I will probably disappear from here, for a priest in this synod I have long ago resolved never to be, and that even though they may relax their views, and it is my firm conviction that Icelanders, who here west move, beware of joining this denomination. Páll Þorláksson has a completely different opinion on this than I do, because he appreciates so well the old Lutheran interpretation of the literal rhetoric by the Norwegian clergy.” It’s worth pausing here and consider the words of the pastor. He writes off the Norwegian Church as a future career, even warning his countrymen not to connect with it in any way. With these words it can be said that he is declaring war on his friend Páll Þorláksson, but at the time the aforementioned letter was written, Páll was finishing his theology studies at this same Norwegian church with the intention of becoming one of its pastors. It is also noteworthy that in his words there is perhaps the hope that the Icelandic colony in North America will become a reality and then he will become a pastor there. It also came to light that he was a staunch supporter of the ideal that Icelanders should settle somewhere remote, preferably outside North American societies where the Icelandic heritage could be preserved and the Icelandic language preserved for the foreseeable future. In the conclusion of the letter to Helgi Hálfdánarson, Reverend Jón says: “Jón Ólafsson is doing well here, and he has written a bit here in a Norwegian newspaper about Iceland.” What was Jón Ólafsson he thinking about in the spring of 1874?

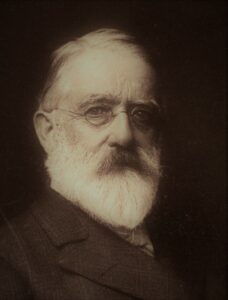

Professor Rasmus Bjorn Anderson and family at their home in Madison, Wisconsin

Iceland’s friend Willard Fiske

Land search: Everyone who came to the west in the winter of 1873-1874 experienced unemployment that spread to almost the entire continent. Many came home with little money in the fall of 1873, and some were almost destitute. Páll Þorláksson heard from many needy people, both in Milwaukee and north in Ontario, Canada. He used his connections with the Norwegians in Wisconsin and they raised money for the unemployed in Milwaukee and for those in the Icelandic settlement in Rosseau, Ontario. Vigfús Sigurðsson had come to Ontario in Canada and said about Páll’s fundraising in a letter to Iceland: “…. and then came unexpected help from Mr. student Páll Þorláksson, who was so decent to send them (settlers in Rosseau) unsolicited considerable financial support from the collection of donations among the Norwegians for the Icelanders; in addition, he has provided other helpfulness and kindness that will never be fully appreciated.” That winter, several Milwaukee leaders used the time to gather information on areas in the United States that might be suitable for Icelandic settlement. These were men like Jón Ólafsson and Ólafur Ólafsson from Espihóll and Jón was particularly interested in areas in the western United States. Luck was with him because the interest of many scholars in the United States in Iceland this winter was great because they knew the thousand-year history of the nation and knew that a lot was going on in Iceland in 1874. People like Willard Fiske at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York and Rasmus B. Anderson in Madison, Wisconsin was particularly enthusiastic, and Fiske was responsible for a beautiful book shipment to Iceland. The Wisconsin State Journal published an excerpt from Fiske’s letter to Anderson on May 24, 1874, in which Fiske states that a bookcase has been sent to Iceland. A lawyer in New York, Marston Niles by name, sent to the United States Congress a request to acknowledge the gift of books to the Icelandic nation and it was approved. Jón Ólafsson was in touch with Rasmus B. Anderson and he put Jón in touch with Niles. Jón discussed the future of Icelanders with the lawyer who suggested that Jón read a book about Alaska, Alaska and its Resources, which was published in Boston in 1870 and describes the local conditions in detail. Jón and Ólafur Ólafsson were both impressed by the work. In discussions among Icelanders about settlement sites, land search was discussed regularly and what to look for. Some had gained experience in American farming and were able to contribute. Finally, there was the following opinion:

| 1. That the colony has an independent government and that there is as much freedom as possible |

| 2. That it is more fertile land and resources than in Iceland |

| 3. That there is an abundance of land that newcomers can receive for free |

| 4. That there is so much employment there or that land is so profitable that newcomers do not have to suffer in the beginning. |

| 5. That there is enough timber for homes, buildings, and fuel; but not a solitary forest, which is difficult to cultivate. |

| 6. That the climate is not too different from Iceland’s; spring and autumn milder, summers longer, but not much hotter than there |

| 7. That the land lies by the sea |

| 8. That it is adapted for livestock farming, and that work is completely different from what is happening in Iceland |

| 9. That it so happens that Icelanders can live alone in the country, without foreign peoples scattering among them. |

People’s ideas about the Icelandic colony have been shaped, as can be seen in the opinion from the above requirements. Undoubtedly, this has been thought of as guidance because an area in North America that met all of these conditions was difficult to find and was never actually found. Ólafur Ólafsson was not the only one thinking of options because he met in the spring of 1874 with Páll Þorláksson, Sigfús Magnússon, Jón Halldórsson, Sigurður Kristófersson and Árni Sigvaldason to organize a land search and an association was established. The places that Icelanders had known in the United States and Canada at that time did not meet important conditions such as e.g., set out in point 9 above. That was one of the keys. The place that people had gotten to know was Alaska, and a meeting was called in Milwaukee in June, where it was decided to send an inspection committee west to “survey the country and get the clearest knowledge of it.” The main promoter of this trip was editor Jón Ólafsson. In his essay “Alaska”, Jón says about the meeting: “About this time one of my friends and a friend of Iceland (Mr. Niles) drew my attention to Alaska; and brought the matter to others and everyone was impressed. I read Dall’s book and sought all the information I could about the territory; then summoned the people of Milwaukee to a meeting and explained the matter to them; suggested choosing three men to go and explore the land, and they should do so at their own expense. I offered my participation to those who would be chosen, with the help of my friend Niles in New York, to provide them with at least some financial relief in the journey or some free travel. I was elected with all the votes for the trip and Ólafur Ólafsson and Árni Sigvaldason. Árni later could not go; but Ólafur and I took Páll Björnsson in his place. Icelanders in Wisconsin then sent a petition to the President of the United States asking him to support and assist our expedition. He answered that question well and offered us to warships ready in San Francisco to sail to Alaska; it was a sailing ship with 18 cannons and over 200 men.” (See more in Settlements / Alaska). Jón took part in other matters because he sat on a committee that was tasked with preparing the Icelandic National Remembrance Festival on August 2 that summer, the same day as a similar festival was held at Þingvellir in Iceland.

Páll Þorláksson in 1875

National Remembrance Festival: The spirit of Milwaukee was special in early 1874. About 200 people from all over Iceland had arrived, some arriving in the fall of 1873 and others well before. Unemployment was high in North America and it pushed people to start farming somewhere together in an Icelandic settlement. The year was also significant in the history of the Icelandic nation, which attracted some attention from western newspapers and magazines. Reports of the Danish king’s arrival in Iceland, a new constitution and celebrations at Þingvellir on August 2 reached the west and were widely discussed in Milwaukee. The western Icelanders were filled with national pride and even though they had emigrated, they still had a love of Icelandic patriotism, an ambition to preserve the Icelandic heritage and the Icelandic language in the West. It was therefore not difficult to gather individuals for a meeting in the city during the winter to discuss a possible National Remembrance Day on August 2 in Milwaukee. Probably Jón Ólafsson and Ólafur Ólafsson from Espihóll had led discussions about this during the winter, because men like Reverend Jón Bjarnason and Páll Þorláksson were busy elsewhere, Páll studying theology in St. Louis and Rev. Jón teaching at Decorah, Iowa. Both came to the city in the spring and took part in the preparations for the festival. Reverend Jón was challenged to sing Mass on the morning of August 2 and preach from the 90th Psalm of David, which was to be used throughout Iceland on August 2.* Páll Þorláksson was commissioned to negotiate with a Norwegian congregation in Milwaukee for the use of their church in the city center that was easily accessible. At the end of July, a committee of men and women was formed to finalize the program, and Páll Þorláksson, his father Þorlákur Gunnar Jónsson, Jón Ólafsson, Friðjón Friðriksson, Ólafur Ólafsson, Jón Þórðarson, and the women Lára Guðjohnsen, the sisters Ólöf and Jakobína Jónsdottir from Espihóll, and finally Sigurjóna Grímsdóttir Laxdal. Reverend Jón Bjarnason wrote about this first national commemoration festival of Icelanders in North America and the following was published inthe book Minningarrit Sr. J. B. in Winnipeg in 1917, and says in one place: “Our national celebration began with an Icelandic service, which began in the afternoon in a church in Milwaukee belonging to a Lutheran congregation of several Norwegians in the town. The author of this letter celebrated this occasion and sought in his sermon to turn people’s minds to praise the Creator, for the thousand-year struggle of the Icelandic nation, and to pray for every Icelandic breath for centuries to come. It is the first Icelandic mass in the West, and in addition to Icelanders in attendance, a large number of people, especially Norwegians, so the church was packed and overflowing. ” (See more Icelandic Heritage / Milwaukee National Remembrance Festival). After Mass, there was a procession from the church, along several streets of the city to a clearing in one of its suburbs. Speeches were gived, refreshments were offered, singing and joy. Following the festival, an association of Icelanders in the West was established with the aim of “preserving and strengthening Icelandic nationality among Icelanders on this continent” and it would be a “liaison between Icelanders here in the West and our countrymen at home in Iceland or in other countries.” ‘(See more Íslensk arfleifð / Íslendingafélag í Ameríku). It is safe to say that the events of this day, August 2, 1874, laid the foundation for Icelandic festivals in the West as well as the activities of Icelandic associations throughout North America for decades, as well as to this day. When the first Icelandic Day festival was held in Winnipeg at the end of the 19th century, August 2 was the day chosen and the program was based on Mass, parade and celebrations where speeches were made. To this day, the program of the Icelandic Festival in Mountain, N. Dakota and the Icelandic Day in Gimli, Manitoba are basically the same as in Milwaukee in 1874. The wording of the charter of the Icelandic National League of North America in 1919 is based on the same commandments as the Icelandic Society’s law in America in 1874. The year 1874 and the events in Milwaukee thus marked a turning point in the young history of Icelandic emigration in North America. Icelanders in the West should look for an area for a new Icelandic settlement where Icelandic heritage and language should be preserved for the future.

* “Lord, you have been our refuge from generation to generation …” Reverend Matthías Jochumsson wrote a hymn in this year (1874), “Oh, God of our country,” based on this which later became the national anthem of Iceland under the song of Sveinbjörn Sveinbjörnsson.

English version by Thor Group.