Paleo-Indians hunting Photo: AHS

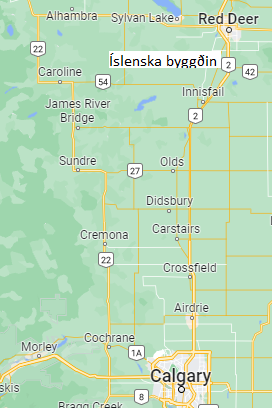

Province of Alberta: In western Canada, the southern Alberta landscape consists of grasslands, where summers are hot and dry, and snowy winters are very cold. Agriculture now consist largely of grain farming such as for wheat, and ranching for cattle. To the west, on the British Columbia border, are the majestic Rocky Mountains, location of the well-known tourist towns of Banff and Jasper. In this region, Icelandic settlement principally occurred near the farming town of Markerville, as well as Innisfail and Calgary, about 100 km (62 miles) from the mountains. H. Thorleifson.

The Paleo-Indians came to the plain where Alberta is today 10,000 years ago. They came from Siberia to Alaska, which was then connected by land across the Bering Strait. Some went south on the east side of the Rocky Mountains, others along the coast to British Columbia and from there across the Rocky Mountains to the plains near Calgary. Over the years, indigenous peoples emerged on the plain, such as the Plains Indians, Blackfoot, and Plains Cree, who followed bison herds, while to the north of the plain lived Woodland Cree and Chipewyan who caught fish and various mammals in traps. In 1670, the British corporation Hudson’s Bay Company obtained a license for a fur trade on the Canadian plains and gradually commercial sites were created. Small villages were formed, and agriculture grew. Alberta was created in 1882 as a district in the Northwest Territories of Canada and gradually increased its population. At the turn of the century, the people demanded the creation of a new province and finally in 1905, Alberta became the third province on the Canadian Plains. The name was in honor of Princess Louise Caroline Alberta (1848-1939).

Icelandic Settlers

Jónas J. Húnfjörð (Hunford) wrote about the settlement in Alberta and the first episode of his article appeared in the Almanak in 1909. Let us give Jónas the word: “The settlement of Icelanders in Alberta began in 1888 from the Pembina settlement in North Dakota. However, Ólafur Guðmundarson – Goodman – had previously moved with his family to Calgary, probably a year earlier in 1887, and his father and brothers, who moved a little later than him and settled with Ólafur. More on these men will be mentioned later in the settlement episode. There were several explanations why people wanted to move away from the fertile, productive Pembina area; it was not for the reason that men did not know that Dakota was the riches and prosperity of the future which was likely to repay in abundance, the hard work and expense of the settlers; but it was also seen that it took time; took both a long time and a lot of money, so very uncertain was it that some would make it through this ordeal. Most of the Icelanders who moved there, both from New Iceland and from the old country, had come there with no money; many had to plunge into large debts in order to conquer the lands. Many people took the advice to mortgage their property and even everything they owned for large sums of money to buy farm animals and tools. The loan was obtained but with very high interest; and naturally the grain-growing which was then in its infancy and childhood could not give us a quick and abundant dividend, so that the borrowers, with some tolerable means of subsistence, could escape through the oppressive claws of the mortgage. At the time, a similar attitude of some and their kinsmen around 1874 either to become enslaved to usurpers and the rich man, or to abandon their land and property, and it became as before, that they took the latter option. There was another reason for the move from Dakota, that there were not so few men there, both family fathers and single men, who thought of settlement in due time; but in those years, land was very much settled in Dakota near the settlements of the Icelanders, that was considered useful; these men therefore had two choices; either to become late or never independent men, or homestead elsewhere. And the Icelanders were still too brave and proud to give up; they would rather venture into the uncertain, rather than live with enslavement and dependence; they have the courage to establish a foothold on earth and thus make themselves and their descendants successful; no, they wanted to be independent. Then there were some who felt the need to change, because of their health; they found that they could not stand the climate; found that the long winter frosts and the dry, steady continental air would, within a few years, make them age-old and lead to death. For these and other reasons, people are considering moving out of Dakota.”

Meetings in Dakota

“In March 1888 a meeting was called, when there was to be a discussion about moving away in the next spring days. At that meeting were nearly thirty people; those who spoke for the move were Ólafur Ólafsson from Espihóll, doctor Einar Jónasson, and Sigurður J. Björnsson. They clearly showed how appalling the prospects were for many to stay, and not to be alarmed that some of the poor would be forced to let go, if they allowed themselves to be subdued, to encourage their journey as soon as possible. It so happened that it was agreed to prepare for resettlement next spring. It was then discussed where to move; most thought about heading west to the blissful climate of the Pacific coast and had in their minds the majestic diverse view, the western natural beauty, the western sea, the mountains, the valleys, the fjords, the bays, all this was like a magnetic force, which drew the minds of many without taking sufficient account of the difficulties and costs which inevitably must incur to move there. The wiser men, however, did not think it advisable to bind this firmly without sending a man west to explore regions and make other necessary preparations. He should travel at the expense of those who plan to travel west next spring. The meeting chose Sigurður J. Björnsson for the trip, who willingly volunteered. Sigurður was instructed to choose the place where the land options were good and the usefulness of lakes and rivers, because most thought that in the future, livestock, farming, and fishing would be a means of livelihood. Sigurður was also supposed to prepare for the journey with various amenities for the travelers such as with a fare and more. Sigurður was to receive money for the trip to the west, from voluntary donations, and we certainly believe that everyone involved in this matter would contribute money, even though we fear that this amount would be less than was desirable. “Most people had tight-fitting shoes when it came to money, so they had to adjust to the growth.” (Most people were poor and gave what they could.)

Explorer Sigurður Jósúa

Sigurður J. Björnsson Photo: Dm

“Sigurður booked a fare shortly afterwards on the North Pacific railway west to Vancouver; from there he headed north all the way to Nanaimo which was about three hundred miles north of Victoria. (JÞ interjection. In Jónas’ story above, it should have stated … west to Vancouver Island because Nanaimo is 110 km north of Victoria). Sigurður did not have had the opportunity to explore the countryside; but then he said that nowhere had he seen potential sites for new settlers; so as a result that when Sigurd turned back east that he had made no decision to lead his party west to the Pacific Ocean. Some may have felt Sigurður performed poorly in his mission there in the west; but on the whole it seems those ideas had little support. Sigurðr lacked both money and time to go from one place to another there in the west; and it is certain that in that respect he could scarcely carry out the exploration he did as far as the voyage of the Pacific was concerned. When Sigurður came to Calgary, he found Ólafur Goodman, mentioned earlier; they talked about the from Dakota west. Ólafur had then, not long before, traveled north to look for lands around the Red Deer River; appreciated what he saw and that it would be a good settlement area; he said that he would like to say that it would be a good idea for the Icelanders to establish a colony. Ólafur had by then already taken land for himself and his father there, although we cannot say for sure, and if it had been so, it was very natural that he should have favored the Icelanders moving north there; but this did not have to be the reason, for Ólafur became known for wanting the best for his countrymen, which he often showed. He now encouraged Sigurdur to go north and explore the land north of the Red Deer River. But whether the plan was short or long, it was decided that Sigurdur should go north; Ólafur suggested to him to take his brother, Sigfús Goodman, who had previously gone north and was therefore familiar with the route. During that trip, Sigurður explored the land north of the Red Deer River, three “townships” (counties) “for Icelandic immigrants. He felt all the land there was good and he decided to have Township 36 Range 1 and Township 36 Range 2 for Icelandic settlers. After that, he returned to Dakota, and arrived there erly in the days of May.”

First group goes to Alberta

“Sigurður, in Calgary, wrote to a few in Dakota and told the progress of his travels. He then says in a letter to me: “My exploration well on the land north of the Red Deer river; the soil there is good and grassy; divided into mainland, plowland and meadow, with forest belts here and there. Fishing is said to be everywhere in rivers and lakes, and winters are said to be shorter and milder in Alberta than in east in Manitoba.” When Sigurdur came south from his journey, men had sold a considerable part of their property; and though men felt bad having to change their intentions to move west to the Pacific Ocean, this did not change people’s plans to move away. Sigurd urged men to move to Alberta; said the land was good there, and the land options seem good. He said that he thought that the space was very much in accordance with the demands of the Icelanders, and in their mood on climate, weather conditions and quality of land. It was then decided to move to Alberta and begin settlement on the land that Sigurður had inspected and decided on in the area. It was both that most of those who had embarked on this journey were poor men, and the other; that their possessions were scarcely sold for half their value; their sums of money therefore were very small, and hardly enough to travel hundreds of miles and then start farming in a remote, uninhabited district. Some were so destitute that they had little more than travel money. On the twenty-fourth of May, 1888, the move had begun; people and luggage were transported by horse-drawn wagon north to the border of the States. In Gretna, they each bought a three-dollar pass to Winnipeg. No live animals were then allowed to move north across the border except on the condition that they be kept at the border for 90 days at the owners’ expense and people saw that too costly. S. J. Björnsson gave the information that cattle in Alberta were cheap, as later proved. It was therefore decided to buy some cows in Gretna nearby and move them west. There they bought 12 cows and 1 calf; the price of them was 20-25 dollars for each cow. Most of these cows were thin and ugly looking, and not properly bred. Then an $85 railroad car was rented to transport these cattle and human belongings west to Calgary; one man had a free ride in the carriage to take care of the animals on the journey. Then the journey continued to Winnipeg. In Winnipeg, people had to stay for almost two days, for the reason that S. J. Björnsson stated it advisable to buy various household items, such as cooking stoves and various smaller utensils; he said he knew that all this was more expensive west in Calgary, which was not really the case when the cost of transportation was added to the sale price for each animal and goods, so it was only an effort, but no benefit; and we will safely say that this was Sigurður’s carelessness to blame.” Now we move on quickly with the story of the group that went on this first settlement trip to Alberta, in the group were Sigurður J. Björnsson, Ólafur Ólafsson from Espihóll, Benedikt Ólafsson, Einar Jónsson, doctor, Sigurður Árnason, Bjarni Jónsson, Jónas J. Hunford, Benedikt Jónsson Bardal, Gísli Jónsson Dalmann. The group also included single men, Guðmundur Þorláksson, Jón Guðmundarson and Jósef Jónsson. And in Winnipeg were added Jóhann Björnsson, Eyjólfur Helgason and one single man, Jón Einarsson. They set off from Winnipeg on May 29 and arrived west in Calgary on the morning of June 1.

Out into the wilderness

We give Jónas Húnfjörð the word again: “People stayed in Calgary, both due to various preparations for activities and also the rains, which were unusually heavy at the time. By mid-June, the party moved out of town and headed north. This journey was both difficult and arduous and there were two main reasons for it: the fact that the farm animals were in poor condition for that journey and the other: that the roads were impassable due to the rains that preceded. It was not uncommon for everything to be unloaded, people and transport; men had to walk almost all the way except for some of the drivers. Many times men had to carry women and children over the worst conditions, otherwise they would have sink in the mud. It was almost incomprehensible what women and children endured and kept their lives and health because the environment and treatment were the worst things imaginable. One is still horrified at the thought of seeing the women on top of the various belongings on the wagons, with the group of children around them, often wet and cold; then come to a stop for the night, and lie down to rest on the wet and cold ground. Day trips were short, sometimes only 10 miles (16 km). On the sixth day, the party reached the Red Deer River, which was later called Myllnubakki. People were therefore very glad to have made it safely, even though many things had gone wrong during the trip, and men and animals were tired and tormented. Then they pitched their tents and rested. “Now the difficult task of getting people, animals and luggage across the river faced the group. Due to the incessant rains of the last few days, the water had risen in the river and it had almost become a big river. It so happened that some in the group had bought wood in Calgary, so it was decided to build a boat. Jónas Húnfjörð wrote and described the transfer across the river: “It was Tuesday, June 27, that the group was to cross the river. The boat was then complete; on it the people, the luggage, and the wagons were to be carried, and the horses would follow the boat, but the cattle were to swim over. This was done and succeeded successfully without any harm, it was a dangerous crossing for both men and animals. When all the moving was over, it was evening and people were sleeping in tents that night … There were 11 families and four single people north of Red Deer. In all, there will have been a total of 50 people, or so. “

We give Jónas Húnfjörð the word again: “People stayed in Calgary, both due to various preparations for activities and also the rains, which were unusually heavy at the time. By mid-June, the party moved out of town and headed north. This journey was both difficult and arduous and there were two main reasons for it: the fact that the farm animals were in poor condition for that journey and the other: that the roads were impassable due to the rains that preceded. It was not uncommon for everything to be unloaded, people and transport; men had to walk almost all the way except for some of the drivers. Many times men had to carry women and children over the worst conditions, otherwise they would have sink in the mud. It was almost incomprehensible what women and children endured and kept their lives and health because the environment and treatment were the worst things imaginable. One is still horrified at the thought of seeing the women on top of the various belongings on the wagons, with the group of children around them, often wet and cold; then come to a stop for the night, and lie down to rest on the wet and cold ground. Day trips were short, sometimes only 10 miles (16 km). On the sixth day, the party reached the Red Deer River, which was later called Myllnubakki. People were therefore very glad to have made it safely, even though many things had gone wrong during the trip, and men and animals were tired and tormented. Then they pitched their tents and rested. “Now the difficult task of getting people, animals and luggage across the river faced the group. Due to the incessant rains of the last few days, the water had risen in the river and it had almost become a big river. It so happened that some in the group had bought wood in Calgary, so it was decided to build a boat. Jónas Húnfjörð wrote and described the transfer across the river: “It was Tuesday, June 27, that the group was to cross the river. The boat was then complete; on it the people, the luggage, and the wagons were to be carried, and the horses would follow the boat, but the cattle were to swim over. This was done and succeeded successfully without any harm, it was a dangerous crossing for both men and animals. When all the moving was over, it was evening and people were sleeping in tents that night … There were 11 families and four single people north of Red Deer. In all, there will have been a total of 50 people, or so. “

Destination – Settlement

“The next day, June 28, people started looking around; everyone had by then had more than enough of the journey, and were therefore glad to sit still; men then dispersed, and sought for the best place to dwell; some had more trouble than others, and did not find what they were looking for, as was shown later; but the distribution of this small poor group reduced the little energy they had left, and to make the life of the poor settlers even more difficult. Now, after 20 years, it is as if a shiver goes through a person, to look back and consider the circumstances, as they were then; to have brought women and children, some with so little, some destitute, out into this wilderness, almost 100 miles (160 km) away from all the comforts of life, was most horrible, as many had to pay for that foolishness for a long time. And no less admirable is the fact that most of these early settlers overcame the difficulties. Most people have agreed that it was right to count the age of the settlement from June 27, 1888.” With these words Jónas Húnfjörð finished his 1st episode, but in the 1911 Almanak he published the 2nd episode and Jónas continues to write: “This story will continue from its first chapter, when the first settlers stood on the north bank of the Red Deer River, and contemplated building their lives, whereever they who chose their land would be best for them for the future. It was previously mentioned that two townships had been chosen for the settlement of the Icelanders. But in one of them was a flaw in that it was missing the sections measurements. It lies mostly west of the Medicine River. (Aside: This river flows on the west side past Markerville to the Red Deer River near Innisfail. Settlers called it Huld.) It is fertile land in many places, in some places quite low. None of this group of settlers took land west of the river; there were two main reasons for this: the river was then in a great flood throughout the summer and was difficult to navigate, and then the land was extremely wet; there were in some places large lakes, which later became fertile highlands, but as then, did not seem easy to use. There was then enough land east of the river and drier. Everyone wanted to achieve a prosperous future land. Then these few men were scattered about Township, 36 Range 1 and Township 36, Range 2, which was then immeasurable, it lies on both sides of the river, still further east. In the unmeasured land, men settled on land without proper markings, and in many places this did not turn right, as was obvious when the land was measured many years later. When some people were less happy with their settlement, which led to some of them moving their farms to more comfortable locations. For those who had been unaware of railroad or Hudson Bay lands, the government arranged for a change of land so that they could keep their farms, if they desired. It is mentioned in Chapter 1 that eleven familes had moved north, who took a ride from Winnipeg; but has forgotten to mention one of them, Sigurður Björnsson, who came from Dakota. There was also in the family of Sigurður Árnason, a married man Guðmundur Illugason, who followed to Calgary, and who later took land in the north. Shortly afterwards, Guðmundur Jónsson and his son Sigfús Goodman also moved north, and settled on their lands.”

“Survival of the settlers in the first years”

“From what has been written before, it is easy to see that there has been no progress in the first two years in the settlement. Most of them had only one thing to do, to cope with the most urgent needs. But good advice was expensive; there was no work to be found closer than Calgary. Some men went there the same summer they moved north, leaving the women and children behind, with the supervision of those who remained. Most of those who went south worked for Ólafur Goodman who had seasonal contract work in Calgary; some of them worked for him the following winter, though for some it would be of little use to them. In addition to the small herd of cattle that had been imported from Manitoba and previously reported, the settlers bought 12 heifers at the age of three, then in the fall, they were good-looking and a good breed but very expensive, 39 to 45 dollars. Most people used the money that they had earned them in the fall for their work in Calgary, this purchase was so expensive for some who had so many mouths to feed, that they put themselves and their families in danger with little winter supplies, Still men survived the next winter through good management. There was a store south of the Red Deer River and everything there was too expensive, but over the winter new settlers had to accept those terms and it became very difficult for them. As an example of how expensive everything was, it can be mentioned that the wheat sack of the poorest quality – XXXX – was 4 dollars. Petroleum oil one gallon 80 cts. Pound of green coffee 33 cts. Sugar cubes 12 1/2 cts and everything else was like this. Almost no one had a cent left over in the spring. That winter was short and spring was very early; released ice early from rivers and lakes; fishing was in the Medicine River which was then fished by most; it saved many people’s lives because there was an abundance of fish in the river during the spring and summer in the first years, it was mostly suckers and pike that were caught. Some caught hundreds at a times and survived those times. So the men looked elsewhere to fist, to the lake that lies north of the settlement and is called Snáka-vatn (Snake Lake); there was a lot of pike fishing in the first years; people brought boats there and had nets for fishing gear. People were stationed there in April and May. People suffered through harsh winds and cold weather. The wind was strong on the lake so many times that it was bad for fishing; Icelanders fished a lot in the lake for the first few years and it was a great benefit to them. That exploitation and fishing were the lifeblood of the settlement in the early years, I consider true; there was so little livestock to mention, as before stated, not many; everything was kept alive during the winter to breed and increase the stock as much as possible.

Fellowship – Postal Services

“The first community happy occasion held in the settlement was on June 27, 1889, at S. J. Björnssons. The few who were then at home in the village attended this celebration; no one was sitting at home; then the future prospects of the settlement was discussed and entertained with singing and speeches, among other things. It was then that Guðmundur Jónsson, brought up for disucssion what this settlement should be called, men agreed then to calling it “Medicine Valley”. Still this name never stuck, rather it has been called the Alberta Settlement or the Red Deer Settlement, but neither is a good choice. There were no means of transportation then. In the beginning people received their mail from Calgary late. It was taken north to the store mentioned earlier; which was later called “Poplar Grove”- now “Innisfail”; there the mail was fetched the first winter with danger and difficulty, as one could not cross the Red Deer River without a boat, often for a long time. Then it was late in the winter of 1889, that L. M. Zage (Aside: he was the only settler north of the Red Deer River when the Icelanders first arrived) he got the idea to have a post office set up; provided the Icelanders and others approved. A petition was made and signed by everyone and sent to the government, which was immediately approved. Zage opened the post office in the summer of 1889; it was called “Cash City”. Zage had the post office for just over a year, but then much to the dismay of the settlers. He said it was not possible to continue it. He said that Icelanders were primitives who had not been able to do business or maintain contact with the outside world. Then the delivery of the mail to Cash City ended. The settlers then, as before, had to fetch their mail from Poplar Grove for the next few months, until the post office was set up at Tindastól, which will later be discussed.”

Transport

Railroad station in Innisfail Photo: forthjunction.ca

Jónas Húnfjörð still has the word, his 3rd episode about the Alberta Settlement appeared in the Almanak 1912. “In the summer of 1890, work was done on a railway between Calgary and Edmonton; it was the C. P. R. Company, which built that track. With that, the problems, as far as the distance from the market was concerned, diminished, although everything was still expensive and remained so for a long time. Around the time the track was laid north, a small town was formed in Poplar Grove, which was then named Innisfail, which then became and is still the next railway station for most of the settlement. But even though things were getting better now, such a great luxury from before, imports from Innisfail were limited and subject to serious difficulties. The Red Deer River was still unhindered, still a challenge to people, either blocking their journey or endangering their lives and property. No bridge or useful ferry was available for several years; it was not until 1902 or 3 that a bridge was built on the Red Deer River, by the government’s action, on the mail road between Innisfail and Tindastoll, resulting from the energetic efforts of Honorable J. A. Simpson, the Provincial MP in the Innisfail constituency, that this difficulty was defeated. After the construction of the bridge over the Red Deer River, the business opportunities of the settlers underwent significant changes for the better, as far as market and trade were concerned. For 14 years, they had to face two dangers when it was inevitable to carry out various necessities on the railway, which occurred weekly throughout the year. Although this obstacle was, as has been said, the most dangerous inconvenience suffered by the inhabitants, there were more obstacles in those years which tired men and held them back; it can certainly not be denied that the outlook for the future was bleak.”

Despair – submission

“It did not take many years before some people began to get tired of the difficulties, which to them was a great pity. It took a strong hope and faith in the future for the willpower and determination not to vanish. The weather and hardship; spring cold and dry and frosty nights werefrequent during the summer, sometimes almost every month; agriculture seemed to give little hope of good results. Though dust had been cast in the eyes of men that a railway should be laid north of the settlement, or as near as possible, within a short time, which never became reality; the interest in the newly built sawmill south of the Red Deer River came to naught. Imports were low in the early years, as demand and speculation told the outside world that there was little hope for the future in Alberta. When all this coincided with the desire of some, it came to pass that some thought of emigrating from the settlement, and others desired the same thing; those who felt this way pointed out that this settlement did not thrive, it could not expect a good future; nothing thrives in the ground due to cold and frost; everything dried up, even the rivers and lakes, so livestock died down from drought and water scarcity, no railway would be built near, no tolerable market for farmers’ products, if any, no school, so the younger generation grows up like the beasts of the field. These were the predictions of some who considered it the only choice to move away, and it was some of the leading men who kept this up. It was in the summer of 1892 that they moved away, a whole group. They were: doctor Einar, Ólafur from Espihóll, Sigruður J. Björnsson, Gísli Dalman and others; then it looked as if the settlement would vanished; these men also encouraged departure; but there were some who did not want to listen to those urging, such as the poet Stephán, Jón Pjetursson, Jóhann Björnsson and various others. It was then that Stephan wrote the poem: “At Parting”. “You go away; but I will stay behind” – Andvök. I p. 275 -; Some of them did not like it at all, but the poem is full of proverbs and truths. “

Að skilnaði

Þið farið burt, en eg verð eftir

Álít heiminn sviplíkan:

Svartir skuggar, sólskins blettir

Sáust hvert sem augað rann.

– Bara víðast vantar Grettir

Vætti illa er sigra kann.

Heill sé þeim, sem hefir þreyju

Höggva í örðugleikann stig!

Sem að dofa dára-treyju

Doða og víls ei spennir sig!

Herðum, lífs sem bónda-beygju

Brjóta, en leggjast ekki á slig.

Þið farið burt, en eg verð eftir –

Auðn í sveit fær manns-hönd breytt

Náman, gullið rauða réttir

Rekulausum höndum neitt –

Edens-leit er lúa-sprettir,

Labb og skæða-slitið eitt.

Mig ei þangað fýsir flytja

Fyrir-bygð sem jörð er öll,

Gerast annars garðs-horns rytja,

Græða ei út neinn heimavöll –

Rúm fyrir þrótt minn, þar sem strita

Þessir fáu að tímans höll.

Þið farið burt, en eg verð ettir

Áset mér að reyna og sjá

Áður göngu lífsins léttir;

Loks hvor stærra dagsverk á,

Sytra, er út við skúr sér skvettir

Skjótt, eða farvegs-gróin á.

Þið farið burt, en eg verð ettir –

Ósk sú mér við hug er feld:

Ykkar vegir verði sléttir!

-Viljug fram á æfikveld,

Brigði-vona haugaeld!

Dreams come true

“This evacuation was a blow to the settlement. The enthusiasm diminished and spoiled the reputation of the settlement in distant places. But the predictions of those who have gone away have now mostly come to naught. Agriculture has now become quite large here and although it is sometimes subject to accidents due to the effects of nature, no one here will oppose the fact that it is of great interest to farmers. The fact that everything was in danger due to water shortages and drought is unprecedented in the twenty years that Icelanders have lived in the Alberta settlement. According to inquiries and experience, this settlement will be better placed than some other Icelandic settlements as far as livestock drainage is concerned. The other is true that droughts sometimes damage the earth’s vegetation, so there is damage. The market and trade have often been unhealthy but have changed and are still undergoing major changes for the better. Public schools have come a long time ago, as can be seen later in the history of the settlement. A railway is now being built a short distance north of the Icelandic settlement and there is a strong possibility that a railway will be built through the Icelandic settlement soon.”

The publisher of the Almanak, Ólafur S. Thorgeirsson, saw reason to emphasize that “The writing style of the honored author has been followed here according to his recommendations”.

Viðar Hreinsson’s masterpieces, Landneminn mikli and Andvökuskáld contain particularly good descriptions of human life in the Alberta settlement that everyone who is interested should read.

English version by Thor group.