The map shows the Icelandic town of Baldur, which was in the southern part of the settlement, in the center is Grund, which has long been one of the main settlements in the settlement. To the north are the towns of Glenboro and Cypress River. Tiger Hills are southwest of Grund. The westernmost part of the settlement reached there.

Province of Manitoba, Canada, southwestern: Southwestern Manitoba lies above a thick layer of shale that extends with related rocks from Brandon, Manitoba to Calgary, Alberta. This layer of shale caused southwestern Manitoba to be above the stony, limestone rich soils of the Interlake, and the clay of the Red River Valley. As a result, the landscape consist of rolling grassy hills, in an area where the soils are well drained and very favourable for agriculture. Icelanders settled in this area, mainly in the Argyle settlement around the communities of Baldur, Grund, Bru, and Glenboro. This area includes the Tiger Hills, and other gently rolling hills, most of which formed as moraines at the edge of the retreating continental Ice Age glacier. H. Thorleifson.

New Icelandic colony in Manitoba: Around 1880, it was clear to most that the future of New Iceland was non-existent in all circumstances there. Ever since the establishment of the colony, one tragedy after another had hit the settlers. The ignorance and inexperience of the settlers played a part, but they could do little about poverty, disease, floods, flies, mud, lack of roads, and isolation. Residents had divided into two groups, one followed Reverend Páll Þorláksson south to N. Dakota where a new colony was formed. The others did not want to leave Canada, preferring to look elsewhere southwest of Winnipeg. John Taylor, who played an important role in the choice of location for New Iceland in 1875, had come to the same opinion as so many others: that a better area could be sought elsewhere in Manitoba. He got his English partner who had been in New Iceland, Everett Parsonage, to go on a tour of the province south and west of Winnipeg. He found good lands in many places, took land himself near Pilot Mound and described large areas north and west of it in his letters to John Taylor.

First Settlers: Another man who gave his blessing to the choice of location for New Iceland in 1875, Sigurður Kristófersson, traveled to the river in August 1880 and together with Kristján Jónsson sailed up the Red River to Winnipeg and on to Emerson at the US border. From there they veered west on their exploration and when they approached Pilot Mound, they met Skafti Arason who had gone on an exploration expedition earlier in the summer and was now on his way back to New Iceland. He readily agreed to accompany them to the area he saw fit. Here it is worth pausing the story, going back to August 5, 1875, when these three westerners confirmed the report of Sigtryggur Jónasson and Einar Jónasson on the exploration expedition undertaken in July of the same year to find areas under New Iceland. They signed the report with these words: “We, who write our names below, have explored the land that the Icelandic envoys have taken for them. We were with them all the time they were here from the west, and we declare that we are in agreement with them about the country and what they have said about it in their report above.” Under this Skafti Arason, Sigurður Kristófersson and Kristján Jónsson and John Taylor confirm with their signatures that they have witnessed the signing. No doubt these men had learned a great deal from their stay in New Iceland and were now better equipped to choose lands. The same will be said of all those who fled from the misery of New Iceland to the fertile plain of Argyle. The aforementioned Skafti Arason wrote a letter on January 25, 1884 to Leifur‘s editor (an Icelandic newspaper published in Winnipeg) who published the following excerpt from Skafti’s letter in the newspaper on February 15, 1884: “A total of 60 Icelandic settlers have now arrived. Some of them have recently taken land, and quite a few have started working on their lands, and on the whole, most have done little plowing, some have plowed about 20-30 acres, and one has more than 50. It is generally considered that livestock farming is more profitable than agriculture, especially due to such a long distance to the market and all products at such a low price.” Skafti rightly points out that there is a long way to go from the settlements to the market to fetch necessities and to sell products for their worth. It was best to go to places like Brandon, Manitou, and Carberry, 60-130 km (37-81 miles) away; oxen were used for such long journeys that were usually made in the winter. But in those years, the plains west of Winnipeg were gradually filled with settlers, and the construction of the railroad dominated. Many took the train and went to the end of the line. It was therefore a great boon when the railway reached Glenboro in 1886. Jón Ólafsson took land in the area in 1882 and named his land Brú. An excerpt from his letter, a kind of report, was published in Lögberg on May 30, 1888, stating that there were 422 inhabitants in the settlement, of which 103 were families and 96 were settlers. From 1885 – 1888, 53 children were born, 13 children died as did 6 adults during the period.

Trade: In the early years of the Argyle Settlement, or until the Winnipeg Railroad reached Glenboro, Icelandic settlers had a long way to travel. Sigurður Kristófersson’s land, Grund (See map) was somewhat central, so he started a small shop in his home in the first years of settlement. He had to go far for goods, so his shop could never meet everyone’s needs. When there were railways both north and south of the settlement, he closed his shop after selling farming tools for a number of years. Friðjón Friðriksson had run a store at Gimli in New Iceland and was prepared when he took the train from Winnipeg to Glenboro in the autumn of 1886. He soon opened a store there in the town which he then ran with excellence for 20 years. There were others who engaged in trade there of various kinds, for example, the sons of Sigmar Sigurjónsson from Einarsstaðir in Reykjadalur, Kristján b. 1878 and Sigurjón b. 1880. Guðmundur Símonarson b. 1866 (son of Símon Símonarson and Valdís Guðmundsdóttir who came west in 1874) traded in agricultural tools under the name W. G. Simmons for years. Friðbjörn Sigurður Friðriksson from Melrakkaslétta was a town councilor in Glenboro who ran a shop there and was in the cattle trade and husbandry. Cypress River served the eastern settlements although few Icelanders settled there. Jónas Halldórsson (son of Halldór Árnason) often wrote to Anderson and ran a shop in the village for years. Kristján Jónsson, one of the first settlers in the Argyle Settlement, engaged in agriculture there for the first few years, but later his mind turned to trade and when a railway was laid around the southern part of the settlement around the Icelandic village Baldur in 1889, he moved there and opened a shop. His father, Jón Björnsson from Héðinshöfði, also ran a bookstore there for as long as his strength allowed.

Freedom Church (Frelsiskirkjan) at Grund

Congregations and churches: Religion was a priority of the settlers of the Argyle Settlement. On New Year’s Day, 1884, the first congregation in the area was founded and given the name Free Church Congregation (Fríkirkjusöfnuður). The first parish committee consisted of Sigurður Kristófersson, Skafti Arason, and Skúli Árnason. As in many Icelandic settlements in the West, disagreements arose between the newly established Free Church congregation and, on July 26, 1885, a new congregation was formed, the Liberty Church (Frelsissöfnuður), at Sigurður Kristófersson’s suggestion. Sigurður Kristófersson, Þorsteinn Antoníusson, and Árni Sveinsson were elected to the first parish committee, while Kristján Jónsson became the congregation leader. Leifur in Winnipeg published an excerpt from a letter from the Argyle Settlement, July 15, 1885. “(July 1885). The opinions of the people in the congregation seemed to be very divided, as a result, many farmers left the congregation and they have already started to form another congregation, which they call the Liberty Church.” Sigurður Kristófersson has obviously been dissatisfied with Skafti Arason and Skúli Árnason, who continued to sit on the parish committee of the Free Church congregation. This dispute will be settled elsewhere.

Reverend Jón Bjarnason returned to to Iceland in 1880, but he had now returned to the West. The newly established parish committee of the Freedom Church decided to call Reverend Jón Bjarnason to provide religious services in partnership with the Free Church congregation. The parish committees of the congregations met on the matter with no resolution, but Rev. Jón was ready to attend the congregation meeting of the Free Church congregation in the area and on March 3, 1886, the pastor called a meeting and chaired it himself. He was willing to provide services to both congregations in the community and did so for years to come. The congregations joined forces to build a church and it was consecrated in 1889 and in the same year, a western theological candidate, Hafsteinn Pétursson, was newly ordained in the area. This is the oldest Icelandic church in Canada.

A congregation was formed in Baldur, and at a general meeting in the village on November 7, 1906, the idea was presented. At another meeting on February 7, 1907, money was raised for a church building and a site was chosen. The construction of the church began and went well. The church was completed in the fall of the same year, and at a general meeting on October 30, 1907, a congregation was formed and named the Immanuel Congregation. The Glenboro Congregation was founded on October 19, 1919 and was the youngest congregation in the settlement.

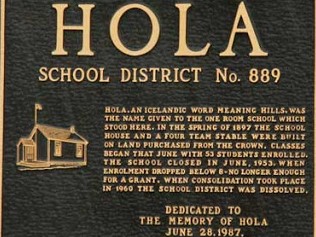

Schools: The school districts (skóli) in the Argyle Settlement were soon formed when it became clear that new settlements were becoming established and the number of settlers increased rapidly. Settlers’ wishes for Icelandic names (Nordic mythology) in school districts were met, but the spelling was not always correct. Teaching in the area started in the summer of 1884, but the oldest school district, Hecla, was founded in November, 1884, and a small school was built. Teaching began there in the spring of 1885 and was only taught during the summer months due to difficult transportation during the winter since no roads existed and any type of transportation was difficult. This went on until 1889, when transport had improved. At that time, there were 120 students in the school. In 1885 a school was opened in the Cypress River school district and another in the same year at Brú. The school district in the southern part of the settlement was originally called Simpson School District and a school was built there in 1892. Its name was changed to Baldurskóli in 1915. Both Mímir and Hólar school districts were formed in 1896, schools were built and teaching began in 1897. Freyskóli began operations in 1896. The century passed without much change, as did the first decade of the 20th century outside that Thorskóli was built in the school district of the same name in 1908.

Schools: The school districts (skóli) in the Argyle Settlement were soon formed when it became clear that new settlements were becoming established and the number of settlers increased rapidly. Settlers’ wishes for Icelandic names (Nordic mythology) in school districts were met, but the spelling was not always correct. Teaching in the area started in the summer of 1884, but the oldest school district, Hecla, was founded in November, 1884, and a small school was built. Teaching began there in the spring of 1885 and was only taught during the summer months due to difficult transportation during the winter since no roads existed and any type of transportation was difficult. This went on until 1889, when transport had improved. At that time, there were 120 students in the school. In 1885 a school was opened in the Cypress River school district and another in the same year at Brú. The school district in the southern part of the settlement was originally called Simpson School District and a school was built there in 1892. Its name was changed to Baldurskóli in 1915. Both Mímir and Hólar school districts were formed in 1896, schools were built and teaching began in 1897. Freyskóli began operations in 1896. The century passed without much change, as did the first decade of the 20th century outside that Thorskóli was built in the school district of the same name in 1908.

Social activities: In a new settlement where all transport was extremely difficult, all kinds of social organizations had to sit on their hands. Many pioneers had taken an active part in social activities in New Iceland and Winnipeg and sought ways to come together. Ecclesiastical fellowship prevailed in every congregation, but outside of that, there were few associations. The so-called Siðabótafélag must be considered one of the most remarkable associations of Icelanders in the West these years. It was founded on March 23, 1884 at the home of Kristján Jónsson from Héðinshöfði. Skafti Arason was the main promoter of this social association. He traveled a bit around the countryside, asked people to read the rules of the association that he himself had agreed upon and pertained to general improvements in shaping the young community. He became quite aggressive in his promotion, both men and women read the rules and signed up for the club. These were the three main rules: 1) not to swear or swear by the name of the Lord unnecessarily, 2) not to drink alcoholic beverages 3) not to start using tobacco after the person has become a member. (See also Íslensk arfleifð / Siðabótafélagið). Stúkur formed early and did many good things. Iðunn was founded on June 18, 1889 and Dagskrá after the turn of the century, and it donated an organ to the Free Church at Brú in 1910. Two women’s associations were founded and did a lot of good work for the benefit of the young settlement. Reading societies followed Icelandic settlers west from Iceland and, almost without exception, one of these was established in every Icelandic settlement in North America. At its peak, four of them worked in and around Argyle. One of the oldest was in the western part of the settlement and played a major role in the construction of the Skjaldbreið meeting house, which was built in Grund in 1896. Another reading society operated in the eastern part, the third was founded on January 28, 1893 in Baldur, and the fourth was founded in Glenboro at the turn of the century. Then another one worked in the Hóla Settlement, north of Argyle.

English version by Thor group.