Ósland is the name of a rather small Icelandic settlement on Smith Island in the Pacific Ocean. The name comes from the estuary of the Skeena River, the second largest river in British Columbia. Since ancient times, it has played an important role for various indigenous peoples, such as Tsimshian and Gitxsan. The names of these nations are related to Skeena because Tsimshian means “in the Skeena River” but Gitxsan means “people of the Skeena River”. The river’s ecosystem and estuary were unique, countless fish species were caught and there were numerous plant species on the banks of the river. The two nations lived in peace and harmony, Tsimshian settled on the estuary and just up the river while Gitxsan lived much further inland. Tribes of each nation lived independently with their own customs and traditions. The river and its surroundings were the lifeblood. There are six species of salmon and at its peak it was said that every year 5 million salmon went up the river to their spawning grounds. The British Hudson’s Bay Company explored the west coast of Canada and set up a trading post at Skeena in 1834 called Port Simpson. Nine tribes of the Tsimshian people lived nearby and were the company’s main customers. However, it was primarily this unparalleled fishing industry that fascinated traders and in the last decades of the 19th century they opened canning factories. For this to work, a fish was needed and that was enough. These circumstances attracted the attention of many in Canada but also in the United States. Around and after the turn of the century, Icelandic settlers in Manitoba began to pay attention to this opportunity and people moved west, first to Prince Rupert which was then growing rapidly.

Ósland is the name of a rather small Icelandic settlement on Smith Island in the Pacific Ocean. The name comes from the estuary of the Skeena River, the second largest river in British Columbia. Since ancient times, it has played an important role for various indigenous peoples, such as Tsimshian and Gitxsan. The names of these nations are related to Skeena because Tsimshian means “in the Skeena River” but Gitxsan means “people of the Skeena River”. The river’s ecosystem and estuary were unique, countless fish species were caught and there were numerous plant species on the banks of the river. The two nations lived in peace and harmony, Tsimshian settled on the estuary and just up the river while Gitxsan lived much further inland. Tribes of each nation lived independently with their own customs and traditions. The river and its surroundings were the lifeblood. There are six species of salmon and at its peak it was said that every year 5 million salmon went up the river to their spawning grounds. The British Hudson’s Bay Company explored the west coast of Canada and set up a trading post at Skeena in 1834 called Port Simpson. Nine tribes of the Tsimshian people lived nearby and were the company’s main customers. However, it was primarily this unparalleled fishing industry that fascinated traders and in the last decades of the 19th century they opened canning factories. For this to work, a fish was needed and that was enough. These circumstances attracted the attention of many in Canada but also in the United States. Around and after the turn of the century, Icelandic settlers in Manitoba began to pay attention to this opportunity and people moved west, first to Prince Rupert which was then growing rapidly.

Icelandic settlements: Icelanders on the plains of Manitoba, N. Dakota and Minnesota closely followed the settlement on the Canadian plains, some moved e.g., from N. Dakota west to the foot of the Rocky Mountains, which later became Alberta. They had sent explorers all the way west to the Pacific Ocean, but there they did not find the land the plains farmers of Mountain and Garðar were looking for. The settlement in British Columbia grew and there were many job opportunities. Canned fish products had grown and fishing was an optimal industry. It should come as no surprise that people from the Westman Islands (Vestmannaeyjar), e.g. Jón Filippusson, Vilhjálmur Grímsson, Þorsteinn Jónsson and Hallvarður Ólafsson, who came west across the ocean in the years 1902-1912, went west to the Pacific Ocean soon after spending some years in Manitoba. When it became clear that there was a huge catch at the mouth of the Skeena River, it was natural for people to look for areas where they could get a roof over themselves and their family cheaply. The beach on the east side of Smith Island was beautiful, wooded almost down to the shore and a short walk to the fishing grounds and from there to the Cassiar canning factory, where most people worked.

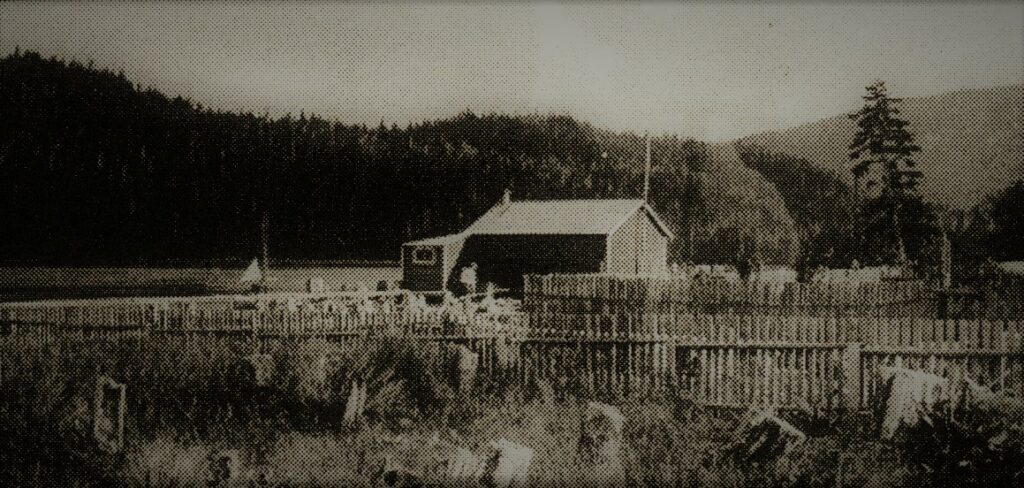

The picture above shows well this special Icelandic settlement by the Pacific Ocean. The houses are not crowded, every family was given enough space to grow vegetables in their home garden, a shed could be built for chickens or goats. Tradesmen built their workshops, many were good carpenters, others worked with iron. The forest provided shelter in the winters, which were seldom harsh, there was plenty of firewood and building materials. Kristján Einarsson from Stóra-Mörk under the Eyjafjöll mountains was considered a particularly good carpenter, making all the windows and doors in the settlement’s houses. He worked very hard one night in July 1917. Before that story, it is appropriate to explain a little about the seabed up to the island, but the picture, taken when the tide was low, shows the mud well. The banks are uneven and that explains why the houses are somewhat higher and further inland. But now comes the story. Sigríður Þorsteinsdóttir, Kristján’s wife, was expecting, contractions started but something was wrong. The midwife, who assisted Sigríður, finds out that the umbilical cord is wrapped around the child’s neck and is now in dire need of a doctor. One was in the Cassiar factory, and now two young men rowed their boat as a matter of life and death and found the doctor who willingly came along. Kristján knew well what was coming, the light had started to fade and it was getting dark. He dressed warmly, turned on the oil lamp and waded into the mud until he reached the sea. There he waited for the approaching boat which soon got stuck in the mud. Krtistján went to the doctor and put him on his back and carried him all the way ashore. The doctor solved all the problems and on the morning of July 17, 1917, Elín Jóhanna was born, who wrote this story in the documentary about Ósland, Memories of Osland. If you look closely, you see the only “road” in the settlement, which was a sidewalk that ran right through the settlement and was the only way to move around town. Using this, the children went to their school, housewives picked up necessities in one of the town’s shops, men carried their nets out on the pier in wheelbarrows, got their knives sharpened by the blacksmith, and stopped at the post office to pick up letters from Iceland or other Icelandic settlements in America. It was also the children’s playground and mothers enjoyed strolling along the path with their children in a wagon or pram on sunny summer days. The settlement did not grow large, reaching about 90 souls at its best in the thirties. Gradually, people moved away from the island, but some remained loyal to the place and built summer cottages.

Portraits:

First schoolhouse in the village. Photo: MoO

The sidewalk through the settlement was paved and laid in such a way that water could flow under it, the tides could be dangerous. Photo: MoO

The people of Ósland all did their best to make human life in the area as good as possible, some of them knew that it could not work to form an Icelandic congregation. For that, they were too few and their settlements remote. It was therefore a great joy when a priest from Prince Rupert came to visit one day and offered his service. He worked at a mission station and sailed between islands, visiting the settlements of the natives and settlers. When his ship, Northern Cross (see photo), appeared on the sea, everyone was celebrating, now a mass would be sung. He had a small musical instrument with him that he used for Mass in the school building. During the summer, he sometimes invited children and teenagers, even mothers, to sail to a nearby island, where everyone spent a beautiful day in peace and harmony. Photo: MoO.