Location of the Settlement:

Location of the Settlement:

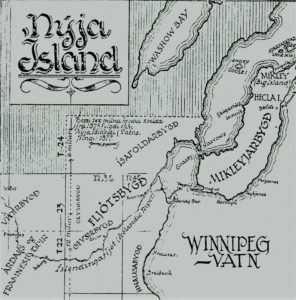

When the Icelanders in Ontario, Canada, in 1874, realized that there was simply no possibility of an area for New Iceland there, they turned west. A delegation went west to Manitoba in the summer of 1875 and explored an area on the west bank of Lake Winnipeg. They went all the way to where the town of Riverton stands today, where there is the estuary of Íslendingafljót (Icelandic River). They went up the river and explored the area on both banks of the river. However, it was not until the turn of the century that settlement began in the area east of Árborg. The area up by the river is divided into several settlements; next to the lake was Fljótsbyggð (Fljóts Settlement), then came Geysirbyggð (Geysir Settlement) and then Framnesbyggð (Framnes Settlement). North of Fljótsbyggð was Ísafoldarbyggð (Ísafold Settlement) and west of Framnesbyggð was formed Árdalsbyggð (Árdals Settlement). There was usually talk of Árdals-Framnesbyggð as a whole, but a distinction was made when reviewing this story. North of the settlement was then Víðirbyggð (Víðir Settlement).

Settlers:

Guðmundur Sigurðsson was the first Icelander to take land in the settlement, he had lived with his father in the Geysir Settlement. It must have been in 1901 that Guðmundur decided to move to an unexplored area and chose land. During the years around and after the turn of the century, there was some movement of Icelanders in New Iceland and in well-established settlements in the United States. Various things caused this e.g. families from Ísafold fled due to flooding from Lake Winnipeg. The rising water level of this huge lake at various times often caused great disturbance in settlements near the lake, but explanations for these fluctuations can be found elsewhere on the website. (See article by Dr. Harvey Thorleifson, geoscientist). In North Dakota, settlements grew rapidly from 1880 to 1890, and many, especially young descendants, were forced to look elsewhere. Thus a large group went west to Alberta in Canada and established a colony there around 1890. Then many went to new settlements, Lundar Settlement, east of Lake Manitoba and from the turn of the century people came to the Framnes Settlement from Ísafold and N. Dakota and then settlers came from Iceland and settled there. From 1902 to 1904, most of the settlers came to settle there.

The first years:

It is noticeable that the settlers’ projects in a new settlement in the area between the great lakes of Manitoba were always very similar, no matter where people started. In the Framnes settlement, it was necessary to break through the forests that grew on the riverbanks, but the Icelandic River (Íslendingafljót) meanders with countless bends and twists. People chose land that stretched from the riverbanks on both sides. Experience had taught people to start by connecting the settlement with the surrounding settlements, thus having an easy path to a store to get the necessities of life. The trail that connected Framnes to Geysir was almost 10 km (6.2 miles) long, but from Framnes to Hnausa was about 32 km (20 miles). It was hardly possible to talk about roads, they were much more trails where people took ox and wagon, and the journey back and forth could take two days. Now this distance is driven in ten minutes. The road to Riverton was longer or about 40 km (25 miles). This came true when Tryggvi Ingjaldsson moved from the Icelandic settlement to Akra, N. Dakota in 1901. He brought horses and a good wagon and decided to set up a small shop on his land. It proved to be the greatest blessing to many. Another settler, Guðmundur Magnússon, who came from Ísafold, picked up goods at the store in Riverton with his horses and wagon and opened a store on his land. They ceased when the village that is now Arborg began to form, and a railway was laid there in 1910.

Félagshús in the Árdals-Framnes settlements. Photo: A Century Unfolds

Meeting house and cemetery:

It has been stated that most of the settlers in the young Framnes settlement came there from other Icelandic settlements in the West. They knew what the most urgent needs were in shaping a new society. A Western Icelandic source says that after the first years and the heaviest flow of settlers into the settlement, the population was about 60 people. Some of them had come of age, but the majority of the population consisted of couples with children and young individuals. Everyone worked diligently to get themselves and their families under one roof, clearing lands and starting farming, but once that foundation had been laid, it was time for a meetinghouse. The meeting house was fairly central and served both Árdals and Framnes. It was simply called Félagshúsið. Such played an important role in every settlement, not only for entertainment but also for Mass before the church was built and also as the school. Home teaching was common in the early years, the children were moved to a farm that was centrally located and taught there. Later, teaching took place in the meetinghouse, and schools sprang up. The number of children in each settlement naturally determined when a schoolhouse had to be built. Congregations took varying lengths of time to form, especially at a time when the religious beliefs of the original settlers were no longer based on the Icelandic national church. But the dead had to be buried, no matter what their views were or what kind of congregation they belonged to in the area where they had previously lived. It was therefore one of the first projects to find a place for a burial ground and since Árdal was in a similar situation, it was decided that a new burial ground should serve both settlements. Tryggvi Ingjaldsson is still relevant because he moved from the land he first chose and moved further west along the river. The cemetery was located on the land he left.

Post Office:

When the government approved a new settlement in Manitoba and indeed everywhere in North America, the land was surveyed, and it was planned. People then chose lands to take according to a special system. Canada’s postal service in Canada was in the hands of each provincial government, which examined the applications of settlers in the many settlements. The applicant submitted an application and chose the name of his post office. Icelandic names were paramount in every Icelandic settlement and when Jón Jónsson Jr., in the Framnes Settlement, submitted his application, a request for the name Framnes followed. The post office in Framnes played the same role as other post offices in all settlements in North America. It was the address of every settler. When a settler wrote a letter in the Framnes Settlement, he specified the post office and wrote “Framnes P.O”. When someone sent a letter west across the ocean, he wrote on the envelope the name of the recipient and then Framnes P.O. as the address in Manitoba, Canada. One explanation for the name changes of Icelanders in the west is that many common names were sometimes in the same settlement. People put a lot of effort into retrieving their mail, perhaps once a week or less, and it was annoying if, for example, the wrong Jón Jónsson went home with a letter that was intended for another Jón Jónsson. The post offices also took care of social needs because it was common for people to meet relatives and friends at the post office. In some places coffee was served and, even accommodation available. Jón took care of the post office all the way until 1922 but then he moved out of the settlement. Guðmundur Magnússon, a farmer in the settlement, took over and took care of it until 1933, when it was merged with the post office in Árborg.

Congregations:

Árdalssöfnuður (Ardals congregation) was founded in 1902, but in 1904 most people in the two settlements, Árdals and Framnes, had joined the Arborg congregation. Churches had not yet been built, so Mass was held in Félagshúsið and Rev. Runólfur Marteinsson sang them, he was then a priest at Gimli. In 1908, Reverend Jóhann Bjarnason became a priest in the northernmost settlements in New Iceland. When the church was built in Arborg in 1911, the Masses in Félagshúsið ended. Icelanders started Sunday school teaching early in their settlements during the Western migration period, especially where it was densely populated. In the Árdals and Framnes Settlements, this teaching took place in Félagshúsið during the first years. The school’s head teacher in the first years was Hólmfríður Andrésdóttir, Tryggvi Ingjaldsson’s wife. Guðmundur Magnússon, a settler who came from the Ísafold Settlement, also taught there at a that time. The two were from the Framnes Settlement, but the teacher of the school from the Árdals Settlement was Eiríkur Jóhannsson. When the Framnes school had been built in 1905, the teaching of the Sunday school took place there. The main singer of the settlement was Þorsteinn Hallgrímsson, who moved to Framnes from N. Dakota. He was the singer at Mass and also at the Sunday school. He practiced singing and regularly performed at local gatherings.

The first Framnes school Photo: A Century unfolds

Schools:

The Framnes school (Framnesskóli) was built in 1905 on Þorsteinn Hallgrímsson’s land on the banks of the Icelandic River. It was in school district no. 1293. There were 17 registered students from January 1, 1905 to June 1, but there were 39 enrolled students in the autumn semester, which shows that the number of settlers had increased considerably during the summer. The first teacher at the school was Kristveig, daughter of Metúsalem Jónsson and his wife, Ása Ingibjörg Einarsdóttir, both from N. Þingeyjarsýsla. The first school committee consisted of Metúsalem Jónsson, Þorsteinn Hallgrímsson, chairman, and Jón Jónsson Jr., secretary. Another school was built in the area in 1913 and was called Vestri. It was in the school district no. 1669. That first school committee consisted of Guðmundur Oliver, chairman, Gísli M. Blondal, secretary, and Daníel Pétursson (Pjeturson). The first year students were 19 and the teacher’s salary was 55.00 dollars per month. The first teachers were Bertha Johnson, autumn semester and Björg Jónsdóttir, spring semester. The school had to be closed for the first year in January and February due to cold and poor transportation.

English version by Thor group.