Beginning of settlement:

Beginning of settlement:

A severe drought in the Þingvellir Settlement of Saskatchewan caused many Icelanders to flee east to the west bank of Lake Manitoba, the first went there in 1894. Most were only engaged in livestock farming to begin with, as the meadowlands were good. The dwellings of people in the early settlement years were traditional, log cabins usually with a thatched roof or, better yet, with a clay roof. Hay and clay were mixed together and the roof was covered with that mixture. Such roofs worked better than turf roofs. Many had to clear their lands, cutting forests to make arable land. Fishing was not great, but people mostly fished through the ice in the winter. Some became big farmers and prospered; gradually buying more land and improving their yields, and expanding the livestock herds. The settlement was originally part of Westbourne County.

When the community was most populated, about 40 Icelandic farmers lived there. Langruth became a farmers’ trading post, where a railway was built in 1908. With its introduction, farmers began to add agriculture and many diversified it with livestock farming. From the beginning, Icelanders took part in the local government and some of them sat on the board every year. In 1898 a school was built and it was in use until 1909. Then a larger and better schoolhouse was built. Many Icelanders have taught at the schools since the beginning. The same year a post office called Wild Oak was opened. When Langruth was built, a post office was opened there. Icelanders took care of postal service from the very beginning. For the first few years before Langruth, the settlers sought refuge in the town of Westbourne, which was south of Langruth, but they also moved west to Gladstone. Trade in Langruth grew rapidly, and trading trips to the aforementioned towns ceased.

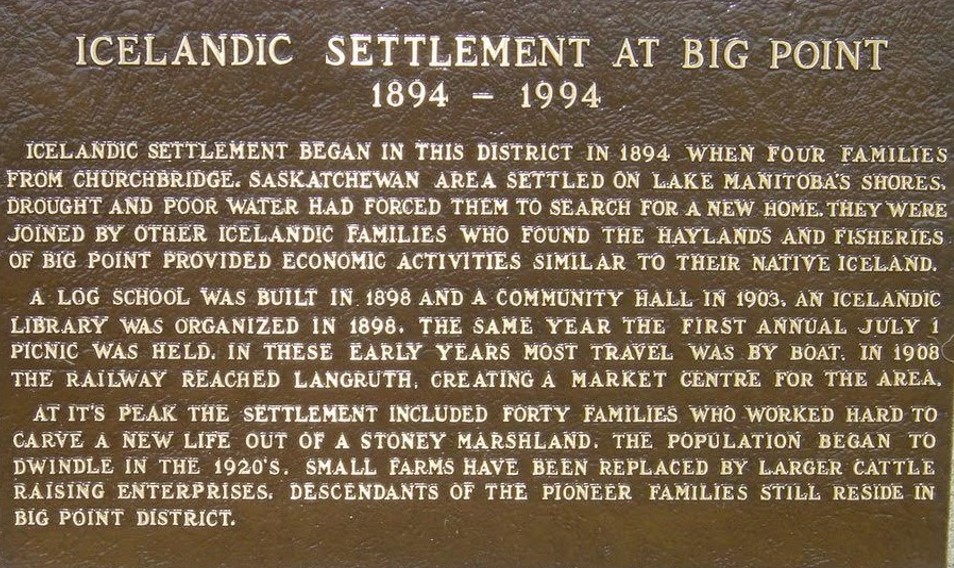

Monument to the Settlement of Icelanders

Transportation – Langruth

During the early years of settlement, there were naturally no roads and therefore all transport was difficult. It was worst in the spring during the thaw and after heavy rains. Then everything was stuck in the wet and mud, horses and carriages. It often took a lot of people to get everything dried out. In 1903, road construction was organized and the Manitoba government invested heavily in local transportation. In many places, where the land was wet, people started digging ditches, thus drying the land. Roads were then laid along these canals, and transportation gradually improved.

In 1907, two young men in Ontario became very interested in the opportunities in western Canada. As was customary at the time, they sought the advice of public officials in Winnipeg for a tract of land. They wanted to take part in building a community on the plains and after a few searches, they liked an area west of Lake Manitoba. The Icelandic farming community was growing well and here they saw opportunities. They bought quite a bit of land and introduced their ideas to Icelanders. They planned to build a village and offered Icelanders business opportunities: buy land and open a store or some kind of service. And the interest of the organizers George Langdon and W. Ruth did not diminish when it became clear that the Icelanders had already sent a request for a railway to the C.N.R railway. Ólafur Þorleifsson showed the guests the settlement and presented their ideas. And the town came into being and is named Langruth after the two men. Shortly before Christmas in 1908, the first train arrived at the settlement.

Trade and Services

In the early years of the settlement, settlers had to fetch supplies from Westbourne, a town about 35 km (21.7 miles) south of the settlement. Gladstone was another town about 50 km (31 miles) west of the settlement. Some of the original farmers had gained some business experience, but everywhere on the plains, farmers tried to make ends meet for their produce in order to be able to buy the most basic necessities. The Icelanders knew the need for a railway to the settlement and it was not many years before they sent a formal request for a stub north into the colony. When comrades George Langdon and W. Ruth announced their plans for a new village in the middle of the settlement, the wheels began to turn. Not all young men in the settlement wanted to farm, some knew the retail trade from other settlements of Iceland e.g. from Þingvalla in Saskatchewan or Mountain, N. Dakota.

In the spring of 1910, Soffonías Helgason and Björn Sigfússon built the first store in Langruth. They ran the store together until 1913, when Frímann Helgason, Soffonías’ brother, bought Björn’s share. Guðni Þorleifsson then bought the store from the brothers in 1914. The picture shows the brothers Soffonías and Frímann, the sons of Jósef Helgason and Guðrún Árnadóttir.

The brothers Finnbogi and Erlendur Erlendsson started a retail business in a new building in Langruth in 1911. Over the next three years, they built two residential buildings next to the store and lived well. In the picture above are, from the left, Ingimundur Ólafson, Finnbogi Erlendsson, Sigurður Tómasson and his wife Katrín Halldórsdóttir, then Erlendur Erlendsson and finally Erlendur Guðmundur Erlendsson.

Guðni Þorleifsson was the son of Ólaf Þorleifsson and Sesselja Guðbjörg Guðnadóttir from Lundarreykjadalur. He bought a blacksmith shop in Langruth in 1913 and ran it for many years. More Icelanders were involved in business, e.g. Eyvindur Eyvindsson, John Thorsteinsson, Björn Christianson and Kjartan Eyvindsson.

Þorsteinn Björnsson (Steini B. Olson) opened a hardware store in 1913. He was born in Markland, Nova Scotia in 1878, where his parents moved to from Nýjabær in Akranes the same year. They were Björn Ólafsson and Guðrún Jónsdóttir. Steini came to Big Point in 1893 and shortly afterwards married Hólmfríður Ólafsdóttir. She was the daughter of Ólafur Þorleifsson and Sesselja Guðbjörg Guðnadóttir.

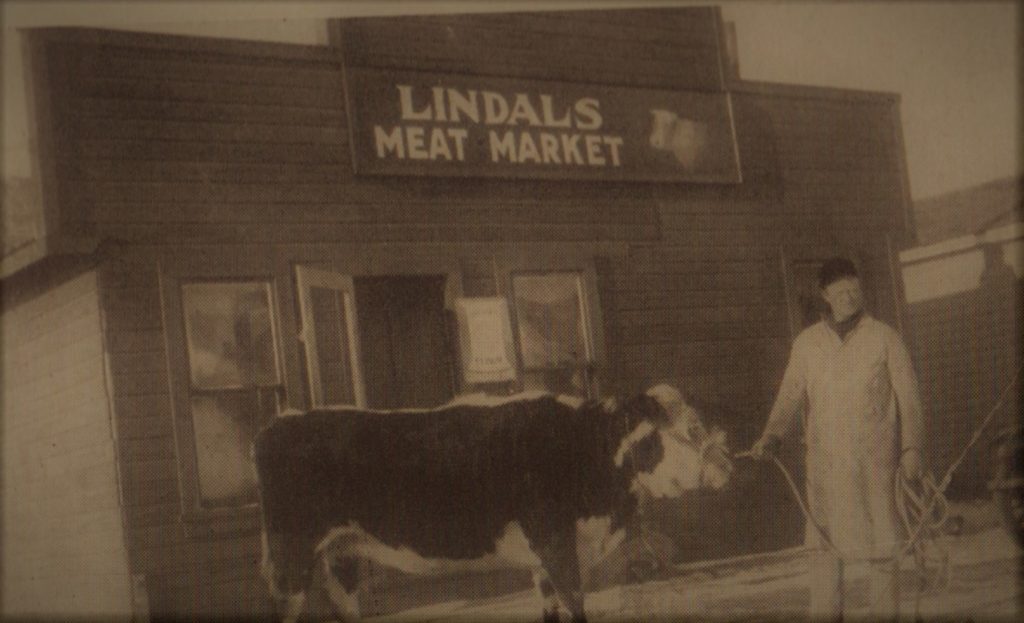

Karl Franklin Björnsson Lindal’s butcher shop

Karl was the son of Björn Sæmundsson and Svava Björnsdóttir and came to the community in 1914. He opened a butcher shop and ran it until his death in 1949. He was a good musician, formed a trumpet band in Langruth and played the organ at services in the church.

Congregations – religion

The settlers in the Big Point settlement, like all immigrants in North America, had to take religious matters into their own hands. Unlike at home in Iceland, there was no national church in Canada and if settlers wanted to practice their religion, they had to organize their own religious activities. From the first days in 1894, it was Rev. Oddur Vigfús Gíslason who came to the settlement and conducted services several times a year. He baptized children, married couples, and buried the dead. Soon a society was formed which was simply called the Christian Society of Big Point Living (Hið kristilega félag Big Point búa).

It was at a fairly large meeting, on April 19, 1906, that a formal congregation was formed and named Herðibreiðarsöfnuður. At the same meeting, Reverend Bjarni Þórarinsson was appointed as the pastor and he held that position until 1916, when he moved to Iceland that year. It was also decided to get Rev. Carl J. Olson from Gimli to visit the village to perform traditional pastoral work. He did so from the autumn of 1916 until the summer of 1917. That spring, the congregation hired Reverend Sigurður Sigurjónsson (Christopherson) to the office and he worked in the area for several years. The congregation was most populous in 1923, when the parishioners numbered over two hundred.

As was the case in most of the pioneer settlements during the Western migration period, people did not build a church immediately in the Big Point settlement, but services were held in the meetinghouse or school in Langruth. The congregation persevered in buying a house in the village for a pastor, at a considerable investment of two thousand dollars.

Jón Þórðarson was elected the first chairman of the parish committee in 1906 and held that position until 1916, when Ágúst Eyjólfsson and later Finnbogi Erlendsson took over. Bjarni Ingimundarson was the congregation’s treasurer for many years and Halldór Daníelsson the secretary from its establishment in 1906 until 1923, but that year Halldór moved elsewhere. Carl F. Líndal took over his job.

The congregation joined the Evangelical Lutheran Church Association of Iceland in the West in the spring of 1916 and selected individuals attended the association’s annual church meeting, men such as Águst Eyjólfsson, Davíð Valdimarsson, Finnbogi Erlendsson, Jón Þórðarson, Magnús Pétursson and Þorleifur Jónsson.

Langruth church

Pastors

Reverend Oddur Vigfús Gíslason was born on April 8, 1836 in Reykjavík. He graduated from Reykjavíkurskóli on July 8, 1858 and from the seminary on August 21, 1860. He took various jobs, e.g. he was a guide for English tourists because he was good at English, he worked in a shop, and was a seaman. He was assigned to Lund in Lundarreykjadalur on September 3, 1875 and ordained on November 28. He served in Grindavík from August 10, 1878 but was relieved of that post on May 9, 1894. That year he moved west across the ocean and was a serving pastor in New Iceland as well as in Big Point. He died in Winnipeg on January 10, 1911.

Reverend Bjarni Þórarinsson was born on April 2, 1855 in Árnessýsla. He graduated from Reykjavíkurskóli on July 8, 1881 and the seminary on September 5, 1883. He was ordained on September 16, 1883 and ordained as a pastor in Kirkjubæjarklaustur the same autumn. He was assigned at Útskálar on March 4, 1896 and was a Provost in W. Skaftafellssýsla from 1885 to 1896. He was released on December 28, 1899 and moved to Winnipeg, Manitoba in 1900. There he became a pastor of Tjaldbúðarsafnaðar and from 1906 to 1916 he served the Big Point Congregation at Big Point. He moved to Iceland in the autumn of 1916 and lived in Reykjavík.

Reverend Carl J. Olson was born in the Icelandic settlement of Lincoln County, Minnesota, on November 24, 1884. He was ordained a pastor on April 30, 1911, and served in Gimli and Big Point. He worked there from the autumn of 1916 until the spring of 1917.

Reverend Sigurður S. Christopherson was born on Lake Mývatn on April 21, 1876. He went west with his parents in 1893. He attended a seminary in Chicago where he graduated in 1909. He was ordained a pastor on June 27, 1909 at the Lutheran Church in Winnipeg and served in the settlements of Icelanders east of Lake Manitoba for years. He was ordained as the pastor at Big Point in the spring of 1917, where he served until 1924.

Lestrarfélag – Icelandic cultural heritage

Wherever in North America Icelandic settlers settled, reading societies were set up early. Members often had a few books and magazines registered with the reading society, which then had the authority to lend them out. The membership fee was a certain amount and thus a fund was created which was used to buy reading materials and so the library gradually expanded. But the reading societies were different and more, they promoted the participation of Icelandic people in them. Debates were organized in the reading societies and individuals were recruited for the competition. They were assigned material in advance and were able to prepare their case. Competitors were given the same material: one was supposed to recommend something while his opponent objected. The audience was often the judge, but sometimes specially selected individuals judged. These debates forced the contestants to think in Icelandic and present their arguments in the best possible language. These debates were popular and were attended by many members.

It was on February 1, 1898, that the settlers of the Big Point settlement formed a long-lived reading society. On the club’s 25th anniversary on February 1, 1923, the club had 514 titles and there were between 30 and 40 members that year. The annual fee was originally 50 cents but was later raised to one dollar. The library consisted of all types of reading material, Icelandic and North American, most in Icelandic but some in English. Icelandic knowledge was on display in every collection and at Big Point the reading society owned all the Icelandic sagas, forty Icelandic episodes published by Þorleifur Jónsson at Skinnastaður, Flateyjarbók in three volumes, Fornaldarsögur Norðurlandi, Snorra-Edda and Edda Sæmundur for example. Of the magazines, all of Eimreiðin and many issues of Andvar and Skírni were there.

Summer Holidays

Icelanders did not flee west across the ocean to forget their origins, say goodbye to land and nation. On the other hand, from the beginning, they considered methods and ways to preserve their ties with Iceland and the Icelandic nation and to commemorate their origins. Early in the Emigration Period, an event took place in Iceland that set the tone: a new constitution was presented at Þingvellir on August 2, 1874. A rather small group of Icelandic Westerners who had come west to the United States that year decided to take part in the celebrations with their own National Remembrance Day on the same day in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. The program of this western festival later became the basis for Icelandic summer festivals in settlements all over Canada and the United States.

In the Big Point community, not many summers passed until the first summer festival was held on July 1, 1903. People gathered from all over the community to participate. The program included speeches, sports competitions, singing and dancing. Speeches at these gatherings were toasts and declarations to Iceland, Canada, and Western travelers. Sports were primarily entertainment; young people competed with older people in racing and tug of war, they competed in Icelandic wrestling and eastern and western settlements competed in tug of war. Narratives in the Icelandic newspapers of these events were similar and often ended like this: “Everything was done with morality and order”.

Although the early years were difficult and hard work, the people at Big Point always took the time to come together for various opportunities to celebrate. Here, an unnamed Icelander (probably Davíð Valdimarsson) gives a speech at the summer festival at the school in Langruth in the summer of 1913.

American sports

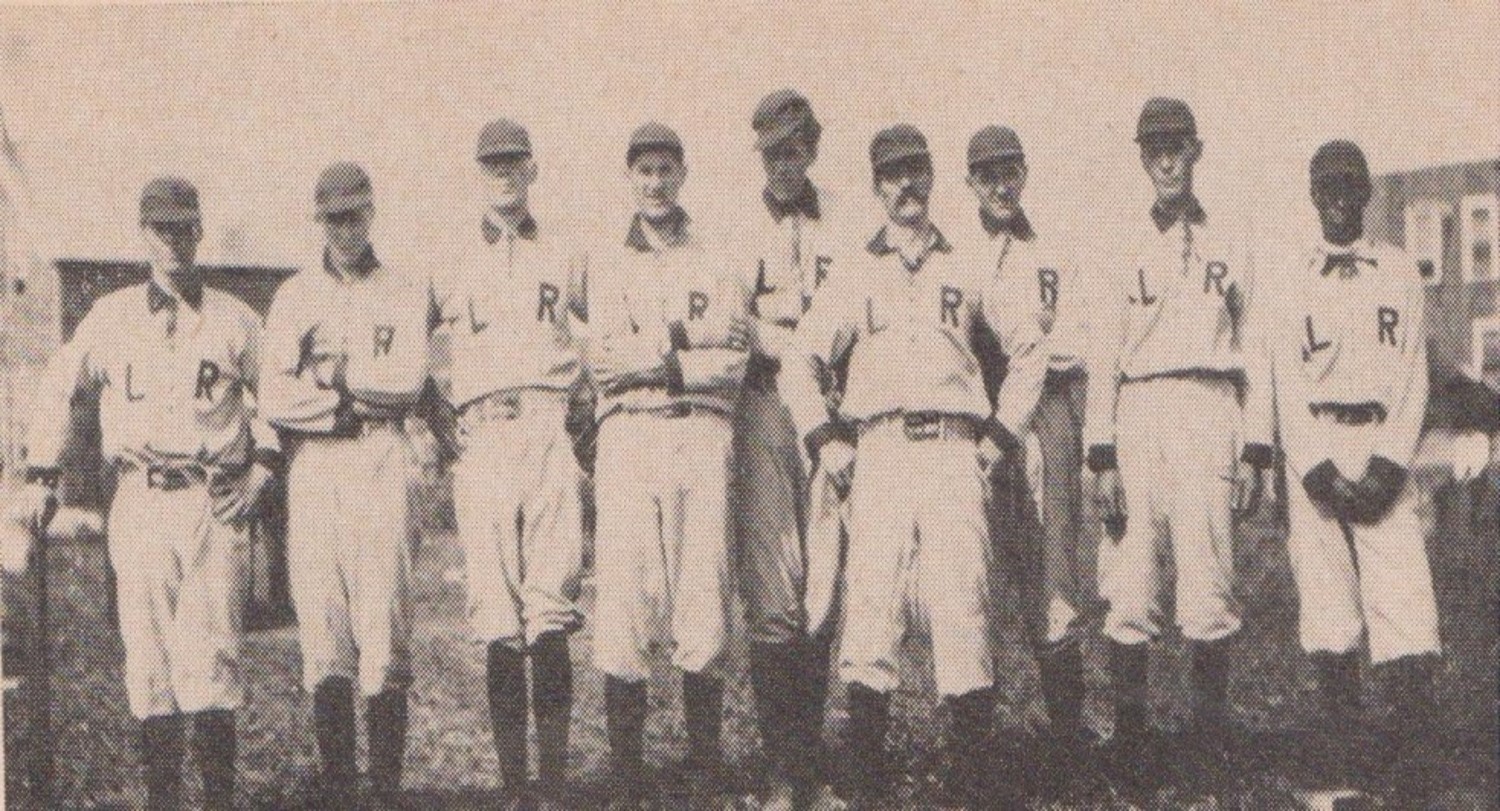

Young Icelandic teenagers were quick to adapt to North American society. One aspect of the adaptation was, of course, participation in sports of all kinds. Young men joined sports clubs, some of which were almost all Icelandic like the Langruth baseball team in 1912. Counted from left: Harry Robertshaw, Valdimar Erlendson, Pete Halldorson, Finnbogi Erlendson, Freeman Helgason, John Oliver, Erlendur Erlendsson, John Finnbogason and Ben Cook.

English version by Thor group.