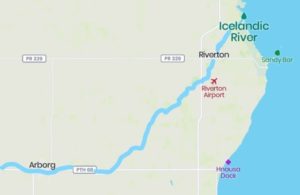

The map shows where the Icelandic River flows near Árborg in the Árdals and Framnes Settlement, through Geysir and Riverton in the Fljóts Settlement into Lake Winnipeg. Map from JÞ.

Photo from Gunnhildur Skaftadóttir’s MA thesis in 2008: Frá Víðirnesi til Vindhljóma.

The Geysir Settlement (Geysirbyggð eða Geysisbyggð) is west of the Hnausa Settlement on the one hand and the Fljóts Settlement on the other. (See settlement map) In 1875, on August 5, Sigtryggur Jónasson and Einar Jónsson completed the report “The Icelandic Envoys” in Winnipeg and certified with a signature. They had taken an excursion north of Lake Winnipeg in July to explore its west bank. Let’s take a look at their writings where they describe the area that later became the Geysir Settlement: “The town north of Sandrif is on a river, which flows from the south out of the harbor (Riverton); it has been called Whitemud River, but we have called it Icelandic River (Íslendingafljót). Up on this one we went in the big boat a third of the way (about 12 km), but then there were breaks and streams in between. With the small boat alone we were able to get over the breaks, and we went a good distance further; but in total we got three-quarters (more than 28 km) of a day’s journey from the estuaries; it is, perhaps, only half a day’s journey when going straight (almost 19 km). As we turned back, a rather large boat was passing along the river, for it is deep there …. As we went further up the river, we encountered willows, as well as some pine forests; they are also further south by the lake. There is also elm, oak and birch. In some places the forest is very thick but so small that the trees are of no use other than to be fences where they stand. The trees are dense because the forest is new, this forest burned some time ago. As the trees grow taller, they are larger. The trunks are usually less than a foot in diameter, but some are heavier. As the pine grows, there is a lot of good wood. However, the land is not covered with forest since the aspens took over on the riverbanks, on both sides of the river where we went, we found swamps overgrown with grass and meadows within the forest everywhere. As a rule, there are no more than 400 fathoms between the grassy areas …. The meadow lands are best along the Icelandic River, but we still believe that sufficient meadows can be found everywhere in this settlement. The settler can therefore already have as many cows as he wants. We have no doubt that the land is the best for grain cultivation, and better than the very best land we have seen in the state of Ontario.” It is quite clear that Sigtryggur Jónasson and members of the exploration committee intended to come here with the first group in the autumn of 1875, the same ones who landed on Víðirnes just south of Gimli.

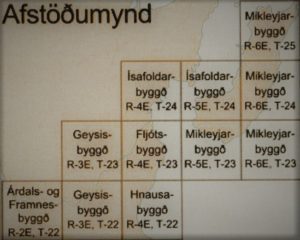

This map shows a few Icelandic farms in the Geysir Settlement. Those who have driven the road from Árborg to Riverton have probably stopped at Arnheiðarstaðir, where Jóhann Magnús Bjarnason landed in 1894. Fögruvellir is close by. Geysir, Pál Halldórsson’s farm, is in the bottom right corner. Drawing by Gunnhildur Skaftadóttir, MA thesis 2008: Frá Víðirnesi til Vindhljóma.

Settlement begins in 1881 when Jón Bjarnason came from Mikley with his wife, Halldóra Guðrún Guðmundsdóttir and his elderly father, Bjarni Guðmundsson. Jón named his farm Fögruvellir and in the first years of settlement, the settlement was often called Fögruvallabyggð. Those who moved here from the settlements of New Iceland first and foremost wanted to devote themselves to agriculture, less ambitious if anyone was fishing in the lake. The community that was formed here in the settlement consisted of settlers from the first years of the Western migration period, their children, as well as new settlers from Iceland coming to the West. This mixture, so to speak, proved to be very successful on the plains of Canada in the years to come, in fact into the 20th century in Saskatchewan and Alberta. The experience of the elders, the emigrants from the first years of western travel, and the diligence and strength of their sons went hand in hand. Added to this was a fresh, Icelandic breeze from home to the west. Their arrival strengthened the use of the Icelandic language in the countryside and the Icelandic heritage became established. Páll Halldórsson was the son of Halldór Jónsson, a pioneer in the Fljóts Settlement. Jón married Jónanna Jónsdóttir in 1880 and they moved to their land in the Geysir Settlement a few years later. The land was called Páll Geysir. He applied for a permit to open a post office and received approval. He then ran Geysir P.O. for several years. A congregation was formed in the settlement in 1890 and the name was Fljótshlíðarsöfnuður (Fljótshlíð congregation) but its name was changed in 1900 and it was then called Geysirsöfnuður (Geysir congregation). The Geysir School District was formally established in 1894.

Transport: The settlers in the Geysir Settlement often had to put in a lot of effort to get to their lands because there were no roads. Many farmers who came from other settlements carried their belongings by land to the settlement but others, e.g. women and children who came from N. Dakota or directly from Iceland took the water route, sailing from Winnipeg or Selkirk north to Hnausa. But from there they had to either walk or ride in a cart pulled by an ox. Necessities were thus transported from stores in Hnausa or Lundi (later Riverton). Settlers could not rely much on the river because it either became dammed up or there was too little water due to drought. Bjarni Jóhannsson, a settler in Engihlíð in the Geysir Settlement, wrote about this in his memoirs (See S. Ísl. In V. 3 volumes pp. 389-390): “The river was not wide, so that when it happened, trees fell into it from each side of the banks. They piled up together and gathered all kinds of rubbish until a dam was formed. These dams were in many parts of the river, which due to them flooded the farms of people in most rains and spring rains. One year it rained heavily. It then flooded the entire lowlands and nothing grew except in the highest parts in the country. Some farmers fenced off their animals on the mounds, and some of them put them on the cowshed roof. But in some lands the water was so high that the beasts drowned. Some towns were flooded so much that the people fled as high as they could where they were and others fled to hills or ridges that rose from the water. In some places it was possible to row a boat to the town gates, and from some farms all the people fled … This waterway often caused a lot of damage. This unrest got many people concerned and some people started thinking about moving away. People even went to the extent to look at lands in western Manitoba and in Saskatchewan, but problems were found everywhere. Then the locals agreed to clear the channel of the river and they cleared all the dams from the waterway. For this necessary work, there was very little funding from the Manitoba government. The day’s work was paid for in dollars. Gestur Oddleifsson in Hagar provided this funding. He was the main man in the village at the time and was sent to address the government, which was chaired by Greenway (Thomas Greenway was the prime minister of the province from 1888 to 1900. Innsk. JÞ), and the mediator was F. W. Colcleugh, a member of the parliament. Gestur always had something out of the ordinary when he made these trips for his locals. Thus, he received some support from the government to lay the road from Breiðuvík (Hnausa) west to the Geysir Settlement.” With these roads, transport improved significantly and it was much easier for farmers to bring their products to market and necessities to the farm.

The Icelandic River. The picture shows the river in the Fljóts Settlement near Riverton because on its banks you can see boats. From there they sailed up the river on an expedition in July 1875.

English version by Thor group.