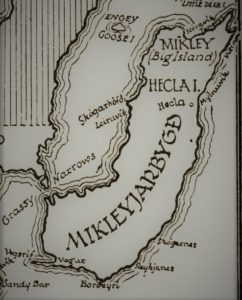

The map shows Grassy Narrows where a landfill today connects the island to the mainland. At the top in the middle of the picture is Engey where Jóhann Elíasson Straumfjörð lived but Jóhann’s first farm was in Borðeyri, at the bottom of the picture

Mikley is an island in Lake Winnipeg in Manitoba that Icelanders first came to in 1875 when New Iceland was formed. The island was the northernmost settlement of the colony. Over 1000 square kilometers in size, it is 30.5 km (19 miles) long from southwest to northeast and almost 10 km (6.2 miles) where it is widest. The island was forested with a small lowland so no settler considered grain growing. Instead, people cleared a small piece of land, built huts and cowsheds. The west bank of Lake Winnipeg, including Mikley, is characterized by a large limestone belt, the coastline is mostly rocky, sandy and wet from the northernmost tip of the island to the southern end of New Iceland south of

The picture shows limestone slabs on the beach in Mikley. It clearly shows how rocky the beach was. Across the channel you can see another island, the so-called Black Island.

Gimli. The people of Mikley soon found a way to fish in the lake, both winter and summer, and fishing immediately became the island’s main source of income. Þorleifur Jóakimsson describes another occupation in “Frá Austri til Vestur” (From East to West) as follows: “In terms of getting a job and getting sawn wood for building houses, it seemed to be a benefit for the settlers of Mikley that the sawmill was there when they settled in 1876, but that was not the case. The mill owners proved to be the worst offenders on the island, cheating some of them who worked for them of wages, and chopping down trees near people’s houses which the farmers were going keep standing, and even threatened to take trees that the landowners themselves had felled and claimed they had every right to do so. In early December 1878, they forcibly seized 200 logs that the islanders had felled and cut for church buildings, and the abuse of the mill owners increased, so that in January 1879 it was thought that people could no longer live there it if their rights were not upheld.” It is worth mentioning that one day not long after, the mill owners had left with all their machinery and were no longer seen.

Life on the island: The settlers in Mikley immediately realized that all contact with other settlers in New Iceland would be difficult in the first years because the transport between much of the mainland and the island was based on sailing on the lake. Neither boats nor larger ships were present in the first year, but soon people built boats and thus travel and transportation improved. The fact that there were so few people on the island in the first years did not offer a vibrant social life, but people helped with necessary jobs and made sure that no one suffered. The leaders of New Iceland were ambitious from the beginning and one of the most important things for them was to get a priest in a young community. Reverend Jón Bjarnason took the call and moved north to New Iceland from Minneapolis. Let’s take a look at Þorleif Jóakimsson’s story in “Frá Austurs til Vestri”, where he describes the priest’s first visit to the island: “The first evidence of church activities on the island is that Reverend Jón Bjarnason came there on November 22, 1877, then newly moved to New Iceland. He held a service in Benedikt Pétursson’s house in Lundi on the 25th (Sunday). About 50 people were gathered there. At the end of the service, children were asked questions in preparation for confirmation, followed by a meeting to discuss congregation matters. The following winter on Saturday, February 16, 1878, candidate Halldór Briem came to the island. He preached in Lundi on Sunday. Many people were at Mass. At the end of the Mass, he interrogated the children, and they appeared well prepared. There were twenty-five inhabitants on the island, but the number decreased shortly afterwards during the emigration years, so congregational life is in a coma for several years.”

Emigration: From the beginning of the settlement of Icelanders in New Iceland on the west shore of Lake Winnipeg, it was obvious that the struggle for survival would be fierce. There was no transport from the settlement to the markets in Selkirk or Winnipeg and the same can actually be said about the travels between the settlements in New Iceland. There were no roads or bridges to facilitate human transport and communication, the land yielded very little and most of the settlers did not have easy access to fishing. Perhaps the worst thing was the spirit of the people, was everyone who went there in the years 1875-1876 satisfied with the purpose of the establishing of the colony? Settling in the wilderness of Canada (New Iceland did not belong to Manitoba in those years) on land that was either rocky, sandy, or wet and therefore largely uncultivable. People came west across the ocean to Canada or the United States to remain Icelanders and live outside the Canadian or American society that was growing rapidly and was shaped by different immigrant groups. New Iceland was to be a haven for Icelandic, Icelandic heritage, and to stand outside Canadian society. Probably the differences of opinion among the settlers were most evident when it came to religion. Two Icelandic priests offered their services, formed a congregation and did a lot of work. One, Rev. Jón Bjarnason, was a priest from home, while the other, Rev. Páll Þorláksson, was educated at a foreign church south in the United States. Who do you think is now more closely connected to Iceland, the Icelandic heritage? How could the people of Páll justify flocking to a priest who had very different views and an educated, Icelandic parish priest from the National Church of Iceland? No settler could prevent the scurvy that plagued the milk-free colony the first winter, let alone the terrible smallpox that followed the following winter. In the years 1875-1878 there was very little progress in the colony, people in most settlements lived in miserable conditions. It was unavoidable that misery prevailed in most places, divisions among people and quarrels reached Mikley, and when the people of Páll began moving from New Iceland to another area south in N. Dakota in the United States, some followed from Mikley. And the Jón’s followers did not stay behind, they gathered in a new settlement in southwestern Manitoba. Their leader, Reverend Jón Bjarnason, turned his back on them and moved back to Iceland.

Development and progress in Mikley: The immigrants soon realized that religion was in their, there was no national church in Canada or the United States. Wherever the Icelanders settled down, they soon began to discuss congregational matters. It was stated above that the people of Mikley brought up such matters in the autumn of 1877, but excitement came in the discussion after Reverend Jón Bjarnason returned to the West and united many Icelandic congregations across North America into one church in 1875. He had not forgotten his parishioners in New Iceland and visited Mikley in 1886. Let’s take a look at Þorleif Jóakimsson’s story, which was published in “Frá Vestri til Austurs“. “In February 1886, Reverend Jón Bjarnason came out to Mikley at the request of some farmers there. He held services and performed various priestly duties. He encouraged people to think more about congregational matters, and as a result, a meeting was held on February 14 to discuss congregational matters, the service of a priest, and more. At that meeting, several people signed up for the congregation that was part of the Icelandic Church Association in the West, which was founded a year ago, and people were then elected to compose congregational laws and so on. Then a meeting was held on March 22, when the church laws were approved and signed by most of the islanders. Congregation members were elected Jóhannes Helgason, Jón Jónsson, Sigurgeir Stefánsson, Ragnheiður Þorláksdóttir (treasurer), helper and scribe Lárus Helgason, assistant helper Stefán Friðbjörnsson. The number of members of the congregation at that time was 26 adults. The congregation, in association with non-congregation members, purchased a meeting house made of sawn wood, 24 feet long and 18 feet wide.”

Helgi Tómasson from Reynistað was a member of the congregation board and was one of those who approved the congregation law on January 27, 1888.

Church, primary school and women’s association: The Mikley congregation was not large in the early years, but in the last decade of the century they still embarked on a major project and built a church. It was consecrated on September 14, 1902, and worship services were normally held there, but until then the Mass was sung in the meetinghouse. There had also been a Sunday school there, but it was now operating in the new church summer and winter. Furthermore, all the preparations for the confirmation children took place in the church.

Icelandic immigrants to America, both Canada and the United States, brought with them to the West various customs and ways of daily life in Iceland. In the small number of people in rural areas at home, teaching had taken place in private homes and this did not change when they came west. In the oldest settlements of Icelanders in the West, there are accounts of some kind of schooling before the establishment of school districts. Mikley was no exception and when the population on the island increased again and again after 1883, a place was found to teach children. Thus, a primary school was run on the island for three months in the winter of 1885-1886 and was attended by 20 children. Þorfinnur Þorsteinsson was the name of the teacher who received 9 dollars a month in addition to food. Settlers contributed to fund the school whose number had then (1886) reached 30. Helgi Tómasson was involved in school management because the primary school was held at his home, Reynistað, before the school district was founded in 1891. The first teacher was poet Jón Runólfsson . With the establishment of a school district, the people adopted the Manitoba Government’s education policy, Mikley became part of Manitoba when the state’s boundaries were moved north in 1881. Reynistaður was the center of the community in Mikley because the island’s post office was set up there in 1887, and all mail was sent there for years.

The women did not shy away from strengthening the community in Mikley because they came together on March 4, 1886 and formed a women’s association. It was called Undína and the founders were: Jakobína Sigurðardóttir, Jóhanna Jónsdóttir, Björg Kristjánsdóttir, Margrét Þórarinsdóttir, Margrét Jónsdóttir, Sigríður Þorsteinsdóttir, Elínborg Elíasdóttir, Guðrún Kristjánsdóttir, Hólmfríður Jósepsdóttir, Þorbjörg Guðmundsdóttir, Valgerður Sveinsdóttir, Sesselja Friðbjörnsdóttir, Guðný Sigmundsdóttir and Sigríður Jónsdóttir. The women’s association worked well and did various remarkable things. At a meeting held on October 15, 1895, the association elected five women to a committee to buy books and there was some discussion about forming a reading society on the island. It was on February 6, 1896 that the reading society was given the name Morgunstjarnan (Morning Star) and it was agreed that it belonged to the public.

English version by Thor group.