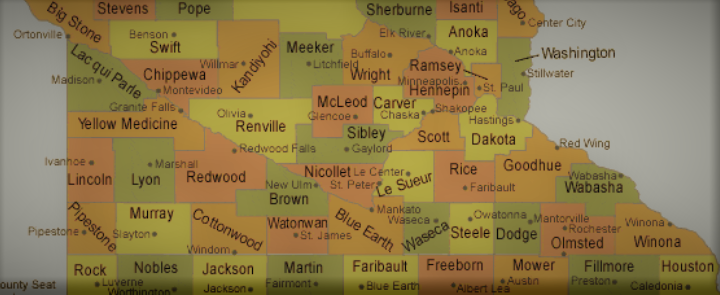

The map shows countless rivers, lakes, and streams that characterize Minnesota.

State of Minnesota, USA: Minnesota is at the center of the USA, bordering on Manitoba and Ontario in Canada. To the west are the Dakota states, to the south is Iowa, and to the east are Lake Superior and Wisconsin. Whereas northeastern Minnesota is cold and rocky, the southwestern portion of the state is not as cold, and thick soils carried in from Manitoba by the glaciers of the Ice Age made the area very favorable for agriculture, after the grasslands that had supported vast herds of bison were tilled in the late 1800s. It was in this southwestern region of Minnesota where Icelandic settlement occurred, near the towns of Minneota and Marshall, in the counties of Yellow Medicine, Lincoln, and Lyon. Although water is not abundant, agriculture flourishes in years when rain is adequate. At present, corn and soybeans are grown across this vast, nearly flat area of productive agriculture. H. Thorleifson.

The territory of what is now Minnesota became a US territory in 1803. Formerly, this area belonged to the Chippewa, Sioux, and Dakota Indians. French explorers became the first Europeans to go there as fur traders and missionaries in 1659. A trading post was established by a French explorer named Duluth in 1678, and today it is a city of the same name. In 1858, Minnesota became one of the states of the United States. The name is from Indian language and means “cloudy water”. The word is compound, “minne” means water and is closely related to “winne” from the language of another Indian nation, the Winnipeg, which means muddy water. Minnesota has more than 10,000 large and small lakes, and many small and large ponds. On sunny, hot summer days, cloud cover is often formed in the sky, which is reflected in the flat water surface, that is, minnesota. The state borders Manitoba and Ontario to the north, Wisconsin to the east, Iowa to the south, and North and South Dakota to the west. In the north, the country is characterized by extensive forests and hills, where logging and mining are practiced. In the middle the plains take over, a lot of grain crops and cattle land. The south part of the state has the most fertile soil. Three large rivers originate in the state; the westernmost is the Red River, which flows north to Winnipeg in Manitoba and on to Lake Winnipeg. The Mississippi River originates in the Itasca State Park in the north of the state, flowing south and out into the Gulf of Mexico via New Orleans. Finally, the Minnesota River flows from the west and merges with the Mississippi just south of Minneapolis.

Norwegian settlers

The US Congress decided in 1849 that the village of St. Paul, on the east bank of the Mississippi, would be the capital of the state. It was then an eleven-year-old trading post. The previous year, four Norwegian explorers had come west from Wisconsin and entered the Minnesota territory. A Norwegian pastor, Rev. C. L. Clausen, traveled up the Mississippi River in 1849 to search the area for a new Norwegian settlement. He came to St. Paul but considered the land around the village unsuitable for the Norwegian colony. He then decided to cross the river to where the city of Minneapolis now stands, but again he was disappointed because he thought the land was only marginally better and sandy. There was no new Norwegian settlement there, but today Minneapolis is considered the capital of Norway in North America.

There were three Icelandic settlement in southwestern Minnesota: Lyon, Lincoln and Yellow Medicine

In the years 1850-1870, Norwegian settlers in Wisconsin sought new territory, increasing their number in the young state from 7 in 1850 to 35,940 in 1870 (HNPA 1925, p. 181). During this twenty-year period, Norwegian colonies emerged in the southern counties, such as Fillmore in 1851, Carver and Winona in 1852, Dakota, Houston, and Nicollet in 1853, and finally Dodge, Olmsted, Steele, and Mower in 1854. Gradually, Norwegians moved west. The reason for this new settlement is that in Wisconsin almost all the land was occupied; young descendants of Norwegian pioneers had to look elsewhere for land. Migration from Norway continued westwards and they demanded new areas for Norwegian settlement. Norwegians divide their history in the United States into three periods: 1. The Norwegian period 1825-1860 2. The Norwegian-American period 1860-1890 and 3. The American period 1890-1925. During the Norwegian period, Norwegians say that their settlers were more Norwegians than Americans. During the Norwegian-American period, they had become more American than Norwegian, and it is worth pausing here to find out what they mean. They used Norwegian and English equally, followed events in Norway and the in United States with equal enthusiasm, celebrated May 17 (Norwegian National Day) and July 4 (US Independence Day) equally, and proudly waved the flags of both countries side by side when appropriate. It was during this period that Icelanders became acquainted with the Norwegian world in the United States. (HNPA 1925, p. 181).

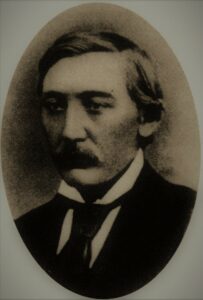

Páll Þorláksson

Icelandic settlement begins in Minnesota

The period of Icelanders’ migration begins in 1870 and ends in 1914. Every year during this period, some Icelanders came to the West, some years a few, others quite a few, and then sometimes large groups. In fact, Icelandic Mormons began moving to Utah in 1854 with a few in the following years, but usually those migrations are not counted in the Migration Period because Western emigrants did not leave Iceland each year. The first westerners of the period came to Wisconsin in the United States, because from there letters arrived in Iceland from a Danish shop assistant who had worked in Eyrarbakki. Páll Þorláksson was one of the first to go there and he, more than others, made an effort to get to know the community. He met Norwegian pastors who invited him to visit the various Norwegian settlements in the state. During these trips, Páll came to the conclusion that Icelanders could learn a lot from Norwegians. It was clear to him that all agriculture in America was very different from that practiced in Iceland. Icelandic farmers in North America would, in the future, have to adopt new ways of working if they were to succeed. He was also fascinated by congregational matters that were in the hands of the Norwegians themselves, there was no national church in the US. He expressed this admiration in letters not only to friends and relatives but also to the editor of a newspaper in Iceland. In one such article to the editor of Norðanfari, dated January 27, 1873, he says, among other things: It is remarkable that in the last 30 years of migration from Norway, Norway seems to be as equal as ever, and yet soon there will be as many Norwegians in the United States as in Norway itself. In this short time, the Norwegians in these countries have done an incredible amount; they have gradually come together, formed congregations, built churches and elementary schools, formed denominations, and a Latin school in the state of Iowa, called “Luther College,” costing the Norwegian congregation $87,000. They paid the full cost themselves. …. It will be best for those who come here, especially Icelanders, not to immediately start gambling on their own, but to learn as much as possible at the beginning of what is useful … ”. (FATV p.24-25) In the autumn, a large group from Iceland came west across the ocean and many of them went to Wisconsin. Páll had discussed the arrival of this group with Norwegian immigrants and investigated whether it was possible for as many as possible to stay with Norwegian farmers for the time being so that they could learn. This was well received and most of the newcomers accepted the offer from Norwegian farmers with thanks. One of them was Gunnlaugur Pétursson.

Gunnlaugur Pétursson and Guðbjörg Jónsdóttir, his wife. Photo: Almanak 1900

Gunnlaugur Pétursson: Guðni Júlíus Oleson in Glenboro, Manitoba, wrote an article about the Icelandic settlement in Minnesota in the book Saga Íslendingar í Vesturheimi V and says the following about Gunnlaug: ”A man by the name of Gunnlaugur Pétursson, born in Jökuldalur on September 10, 1830. His ancestors lived at Hákonarstaðir for many generations, that is to say nine or ten. At the age of twenty-seven, Gunnlaugur married Guðbjörg Jónsdóttir, daughter of Jón Einarsson and Guðný Sigfúsdóttir, who lived in Snjóholt. At that time Gunnlaugur took over Hákonarstaðir farm from his father and lived there successfully until he moved to the West in 1873, when he was quite old. He was one of the first Icelanders to move from East Iceland west to the New World. It is believed that he had some funds which helped get him get established after he moved to the state of Wisconsin and was there for 2 years or so. The Norwegians were very numerous there, and many of them were heading west. Great and beautiful lands were opening up to the public in the western part of the state of Minnesota. The journey there was set, and with them Gunnlaugur went in May, 1875. He rode in a wagon, for which oxen were used, and in it moved his belongings. It was about a 500-mile journey. After a three-week trip, he reached Lyon County and settled on the banks of the Yellow Medicine River and homesteaded there. He named his farm Hákonarstaðir. He was the first Icelander to settle and take land in the state of Minnesota.” Gunnlaugur did well from the beginning in a new settlement in Minnesota, where most of the settlers were Norwegian and German immigrants as well as Americans (a farmer of British descent born in the United States). Not only did Gunnlaugur describe the new settlement in letters to friends and family in Wisconsin and Iceland, but they had an impact because in the following years many people moved to Minnesota and everything went well for the settlers there. In the following years, the Icelandic settlement grew and prospered while everything imaginable failed in New Iceland. Both of these colonies were founded in the same year (1875); in Minnesota by people who had gained experience from Norwegian farmers in Wisconsin, but in New Iceland people came directly from Iceland and lacked all knowledge and experience in North American farming. Once all the land in Lyon had been taken, people took up residence in the neighboring counties of Lincoln and Yellow Medicine. During the early settlement years, there was talk of four separate districts in these counties, but there was just a short distance between the settlements, there was usually talk of the “Icelandic colony in Minnesota”. The town of Minneota is centrally located and 20 km (12.5 miles) east is the town of Marshall, the county seat of Lyon County.

Farming and other industries: In 1900, Ólafur Þorgeirsson’s Almanak published the following description of farming in the Minnesota area in its early years: “The land that Icelanders in Minnesota live on is suitable for both agriculture and livestock farming. Grains are grown: wheat, oats, barley, rye, corn and flax. A variety of garden fruits are grown. Of the products of the earth, wheat is the greatest commodity of the settlers; the average yield will be 12 to 15 bushels per acre of land. (Bushel was a unit of measurement used in the 19th century and was equivalent to 25 kg.) In addition to farming, all farmers are engaged in livestock farming. Many of them have a large number of horses and cattle, sheep and pigs, as well as chickens and other poultry. All the first settlers acquired their lands, free of charge, from the state government. These lands are 160 acres (about 64 ha). The land that Icelanders built on here was completely forest-free land, but since then forests have been cultivated, so now a forest grove is close to most homes. It is both for shelter and splendor.” In the towns of Minneota and Marshall, many Icelanders sought work, many of whom were day laborers, other artisans and a few merchants. A few then set about trading and a few became officials. Learn more at Minneota and Marshall.

Fellowship: The first years in every new settlement were always difficult for all settlers, land had to be cleared and cultivated, houses built, both residential houses and barns. Building materials in the settlement were scarce because there was no forest and therefore the material had to be fetched, sometimes a long way. After several years of hard work, settlers began to consider social issues, such as congregations, reading societies, and gatherings. The beginning of everything in this era was meetings held at the home of one of the settlers who lived somewhat centrally in each settlement. In 1878 an association was formed in Lincoln County which was to establish a reading society, provide books and magazines. The association also worked to find a place for a cemetery and materials for weekly Sunday prayer meetings. This association created two societies. One was called “Framfarafélagið” and similar to the Icelandic Association which was founded in Milwaukee in the autumn of 1874. The society was to promote progress in the settlements of Iceland. After a few years, the second society “Lestrarfélagið” was formed, with its activities aimed at general education and book reading. In 1884, the society set up a meeting hall where meetings and all kinds of events were held. Worship services were also held there for many years. In addition, many Icelanders took part in the activities of organizations that worked for the general interests of society, e.g. agricultural societies, to which settlers of other nations also belonged.

Congregations: Let’s take a look back at the 1900 article in the Almanak, which deals with the Icelandic settlements in Minnesota. It says about religion: “It was in the fall of 1878 that associations began to form ecclesiastical congregations. Meetings were then held in both settlements, and a committee of people from both places was elected to jointly draft congregational laws.” (Insert JÞ: This refers to the East and West settlements. The East Settlement was northeast of Minneota, both in Lyon and Yellow Medicine counties while the West Settlement was in Lincoln County). The East Settlement elected these to this committee: Snorri Högnason, Eiríkur H. Bergmann and Guðmundur Henry Guðmundsson; while in the West Settlement, Árni Sigvaldason and Stefán Sigurðsson. Shortly before Christmas, the same year, this committee met at Árni Sigvaldason’s home and discussed the matter. The two policies that prevailed in Icelandic church affairs in New Iceland at that time had also reached Icelanders in Minnesota. As is well known, Rev. Jón Bjarnason was a forerunner of the policy that followed Lutheran teaching in the same way as the Church in Iceland, but Rev. Páll Þorláksson was a spokesman for the Lutheran teaching of the Missouri Synod, or the part of it called the Norwegian Synod. At first, there were differences of opinion among the committee members as to which policy should be followed. Eiríkur H. Bergmann and Guðm. Henry Guðmundsson wanted to follow Reverend Páll’s policy, but Stefán Högnason, Árni Sigvaldason and Stefán Sigurðsson maintained Reverend Jón Bjarnason’s policy. The committee then agreed on a bill for a congregation law, which was submitted to public opinion the next spring, and a “Lincoln County congregation” was formed in the West settlement and later a “Vesturheim congregation” in the East settlement. Some time later, “St. Paul’s Congregation” in Minneota and then “Marshall Congregation” in Marshall.”

English version by Thor group.