Geology: North Dakota is in the center of the USA, bordering on Saskatchewan and Manitoba in Canada. To the west is Montana, to the south is South Dakota, and to the east is Minnesota. The climate is hot in summer, and very cold in winter, usually with enough rain to support productive farming and ranching in this area of formerly extensive grasslands that supported vast herds of bison until the 1800s. The landscape is subtle due to soft sedimentary rocks such as sandstone and shale, and Ice Age sediments such as mixed gravel, sand, silt and clay. Icelandic settlement occurred near the towns of Pembina, Hallson, Mountain, and Gardar in eastern North Dakota, in productive farmland on the edge of the flat clay plain along the Minnesota border, which extends north to Winnipeg. H.Thorleifson.

Natives: North Dakota borders Canada to the north; west of the state is Montana and to the east is Minnesota. South Dakota is to the south. The state is almost 580 km (360 miles) long and 340 km (211 miles) wide. The name Dakota is derived from the Dakotas indigenous tribe that occupied the region for centuries. The area from the Red River west to Montana and south to Nebraska was called the Dakota Territory until 1888, when it was divided into North and South Dakota, and the two new states joined the Union a year later. It is not known for certain when the natives came to the area, they were there when French fur traders traveled around this part of North America in the late 17th century. They competed with English merchants with the same mission who had recently founded the mighty Hudson’s Bay Company, which became enormously powerful throughout the northern part of the continent well into the 19th century. For a long time there was peace with the natives and these fur traders, it was to the benefit of both. The mid-19th century, however, was marked by the outbreak of the so-called Dakota War in 1862. Indigenous peoples invaded the farms of some settlers, killing the farmer and most of the family. This led to further attacks on settlers and the United States responded by charging more than 300 indigenous peoples with murder, rape and robbery. Most were found guilty and hanged. This is considered the greatest execution in the history of the United States. These events caused many indigenous peoples to flee the area, either to be expelled to reservations or to flee north to the Canadian Plains.

Settlers: It was the merchants of the Hudson’s Bay Company who first set up camp in the Dakota Territory, beginning in the 1790s. From the beginning, it was quite clear that the purpose of being there was not to claim land and settle down. When trade declined, these parties gradually disappeared. However, it was Scottish settlers who came from the eastern United States and went north along the Red River who chose a place on the west bank of the river up to the Canadian border where the town of Pembina now stands. This was in 1812 and Lord Selkirk led this group. As the century progressed, the Red River was a kind of highway north to south, as merchants, settlers, and government officials traveled along it. Some tried to settle west of the village, enjoying the peace and quiet there. However, widespread settlement did not begin until after 1870, and with the advent of the Northern Pacific Railroad in 1872 which was located somewhat to the south of the state, the number of settlers increased rapidly.

Icelanders:

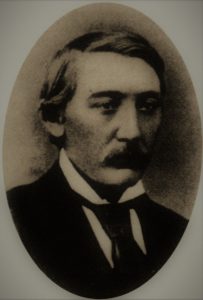

Séra Páll Þorláksson Photo: SÍND

John Betchel Photo: SÍND

The Icelandic migration period is generally thought to begin in 1870 and it ended at the beginning of the First World War in 1914. Every year for almost half a century, some Icelanders went west across the ocean, some years large groups, others only a few individuals. At the beginning of the migration, most went to the United States and settled in Wisconsin. Among them was Páll Þorláksson from Stóra Tjörnar in Ljósavatnsskarð and he contributed mightily to the history of Icelanders in the West during his life. He must be considered the “father” of the Icelandic colony in North Dakota and we must now refer to an essay written by his father, Þorlákur Jónsson, in March, 1882, for Páll, who was then dying in Mountain. Páll then reported and said: “It was in the autumn of 1876 that I first got to know a little about this so-called valley, Rauðárdalur (Red River Valley).” Páll was then an ordained pastor and served a small Icelandic congregation in Shawano county in Wisconsin and other Norwegians in the same area. He also heard that in the autumn a considerable number of immigrants from Iceland were expected, all of whom were heading west on the plains north in Manitoba. He was encouraged by the Norwegian church association, the Norwegian Synod, which he worked for, to take a trip and explore the territory where the Icelanders were going to settle. In the autumn he set off and says in the essay: “Railways were then a short distance north of the valley, so I had to take a steamship on the Red River north to the town of Winnipeg in Manitoba. The captain then told me that he had just moved a large number of Icelanders to Winnipeg, and said that it was sad that so many promising people had been led past the fertile wilderness on both sides of the Red River, north to the land he considered uninhabitable. “ Páll took an active part in the settlement of New Iceland and formed three congregations there. Everyone who was there from 1875 to the beginning of 1878 experienced more tragedy than any other Icelandic immigrant throughout the period. It was no wonder, then, that Páll’s congregations approached him early in 1878 and informed him that they wanted to leave New Iceland. Páll reported: “… in the spring of ’78 I had spent considerable time in New Iceland, and traveled around the countryside back and forth, even out into the wilderness. I thought I had begun to see signs that Icelanders would, sooner or later, never be able to thrive in this country.” He enlisted some settlers to travel south with him in the spring to the United States and look for better lands there. Coincidentally, they got off the steamship in Pembina, because one of them had heard in Winnipeg that a good area was just south of the border, west of Pembina. They decided to investigate.

Accompanying Páll in this exploration expedition were Jóhann Hallsson and his son Gunnar, Magnús Stefánsson, Sigurður Jósúa Björnsson, and Árni Þorláksson. They had to travel on foot and decided to explore the land south of the Tongue River or Tunguá as the Icelanders called it, as it flows east from the Pembina hills. Nowhere did they see houses or any signs of human travel on the plain, but in the forest edge along the river they saw houses here and there, and stopped at some places to get more information about the land to the west. It came as a bit of a surprise that the inhabitants did not seem to have looked around the west of the plain, they were happy with where they were, but someone did know of the hills somewhat to the west. The travelers finally came to Cavalier, but by then they had covered almost 40 km (25 miles). During that time they saw no houses, but in Cavalier lived a German settler who took care of the post office for the area. His name was John Betchel and he had lived there for two years. They stayed with him for one night, but the next day they continued their march. Páll’s essay says: “We walked either north or south of the river, which forms a deep valley, until we came to a mountain view. Then the land suddenly sloped down. We saw green prairie all over the place with forest belts as far as the eye could see south and west. The hills rose to the west. We now thought that the appearance of the country was becoming what we in Iceland call rural. We found the same fertile soil as before on the grasslands. We stayed there for a while, and agreed to return here again, because it was late in the day and we had become tired.” A new colonial area was found and they saw many benefits. First of all, the soil was good, which consisted exclusively of “the fertile soil” and was therefore ideal for arable farming, but in many other places it was a bit woody and there were good pastures. Furthermore, there were large forests in many places, sufficient building materials everywhere and firewood. It was clear to them, however, that there was a long distance to go to the market, but they were sure that markets would come when land began to be built. They decided that Páll’s friends would stay to explore the area better, but he himself planned to travel all the way south to the Icelandic settlement in Minnesota to explore possibilities there. After an excursion south and a short stay in the Icelandic settlement in Wisconsin, Páll returned to New Iceland in the autumn. On his way back north, he stopped at the proposed settlement in N. Dakota and met with his comrades and reported that the area of Minnesota he was visiting was nothing but plains, no forest, and the distance south was much longer for the people of New Iceland.