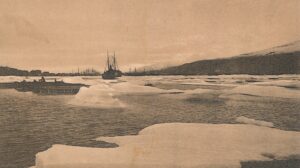

No photos exist from 1880-1881 but here is one showing ice in the harbour of Akureyri July 12, 1915.

Let us briefly examine the situation in Eyjafjörður in the winter 1880-1881 and consider the diary of Björn Jónsson, editor and owner of Norðanfari in Akureyri.

In the fall he prepares himself for the winter: “The butchering done, head cheese made, pickled and stored for consumption during the winter if God allows man to live.”

November is busy, many visitors in town “and much excess drinking and disorderly conduct”. The hard winter is not here yet. It keeps on snowing, so in early December the number of mice has increased tremendously, men at a loss how to get rid of the beasts. “Unusually large number of mice throughout rural communities, cannot be kept out of farms, farmer at one place in Eyjafjörður counted as many as 350.”

News of three icebergs in Eyjafjörður and folks in Grímsey saw nothing but drift ice north of the island. Blizzards in Akureyri and snow so thick everywhere that only the tallest and strongest can move about town. On December 29, the mail from the south at long last reaches town, five horses carrying heavy chests of mail; the mailman had left Reykjavík on December 4.

Church attendance was minimal during the winter 1800-1801

Immediately following the New Year, the storms increased. Snow and freezing temperatures left their mark on January, but God alleviated the hardship somewhat. A dead whale, frozen solid, is discovered near Þórustaðaland, is instantly butchered and the meat sold on the spot. There was a significant decline in church attendance in Eyjafjörður; none of the churches are heated so no services can be held. The daily frost (temperature?) reaches -20° to -30°C, sometimes more. Merchant Edvald E. Möller is curious; he wants to find out how thick the ice is covering the sea outside Akureyri. On February 25, he chops and chops to make a hole and measures: one and a half meters. A month later Björn checks the outside temperature, -32° on the Réaumur scale or -40°C, and looking out to the sea, he wonders how thick the ice can be. As far as he can see, the entire Eyjafjörður is frozen, the ice is snow covered, a dark spot of water nowhere to be seen. Men do not hesitate to walk on it, some even travelled on foot to Akureyri all the way from Siglufjörður.

In early April, Björn writes that some farmers are feeding their livestock with cows’ milk but a few are fortunate enough to have some horsemeat and liver- and blood-sausages that they salted in the fall as a late winter feed.

On May 15, Björn writes spring is here according to the calendar, but “No relief can be had from the sea as the ocean is filled with icebergs.”

A little less than a week later, Saturday, May 21, he writes: “No new developments except the ice is beginning to break here in the harbour of Akureyri, slowly drifting away yet some ice remains stuck on the shore.”

The editor also mentions people have noticed plenty of fish in the bottom of the fjord.

In his annual report on “the general conditions”, the Sheriff of Eyjafjarðarsýsla shares Editor Björn’s sentiments.

Winter was here as early as November, wrote Sheriff Stefán Thorarensen, “with unstable weather, heavy snowfall, icy conditions, much frost everywhere so no grazing was found anywhere. Such has been the situation to the end of the year (1880).”

The new year arrived with very much the same weather the old year had left, Stefán stated. “Severe frosts lingered throughout the whole winter, worse than anybody had ever experienced before. This meant neither sheep nor horse found a bite and had to be brought into shelter.”

The above is based on research by the Icelandic Historian Jón Hjaltason and his article ´´Harði veturinn 1880-1881´´. English version by Thor group.