Thiel College

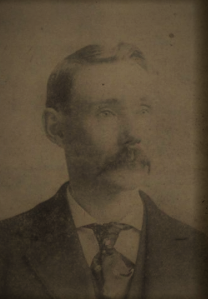

Björn Stefán Brynjólfsson

Young Icelandic men in Winnipeg mixed with their peers of other nationalities in the early years of settlement. This generation of young people moved west to America with their parents during the first decade of the 1870-1914 migration period. This was the case with Björn Stefán Brynjólfsson from Skeggjastaðir in Húnavatnssýsla, who was born on November 3, 1864. His parents, Brynjólfur Brynjólfsson and Þórunn Ólafsdóttir, moved west with their children to Canada in 1874 and spent the first winter in Kinmount, Ontario. From there they moved east to Markland, Nova Scotia in 1875, where they lived for six years before moving to N. Dakota. Björn Stefán stayed in Markland for a shorter time because in the autumn of 1879 he enrolled in a Lutheran university, Thiel College, in Greenville, Pennsylvania in the USA. He would have initially intended to study theology there on the advice of his father, but was forced to drop out of school due to eye disease. From there he returned west to Winnipeg in 1880, where he sought companionship with young Icelandic intellectuals and was successful. He had become acquainted with the literary interests of fellow students in Pennsylvania and their society, and soon he got his interested countrymen in Winnipeg to form a society. Friðrik J. Bergmann writes about this organization in the Almanak in 1905: “Most of the activities were in English, because he was naturally better at English than Icelandic. The society was given an English name and called The Oriental Literary Society, not because its members intended primarily Oriental science for themselves, but because the sun is in the east and illuminates the whole world and warms with light and heat. Likewise, this society was meant to be a tiny sun, which roamed the darkness of ignorance and brought to men the light of knowledge and the warmth of education. Its motto was in Latin: per gradus – foot by foot, so no one would think they were going to do everything at once. This society held its meetings behind closed doors. Looks like it has been laid out in various ways and with less benevolence. Some were so bold as to call it for this reason a secret society or a Masonic society; even a magic society had some allowed themselves to mention it, and they have probably considered it the chief intention of practicing Egyptian wisdom, which has long been regarded as more or less the same as sorcery. Of course, this was all for fun, but “unfree” will seems to have it, after the frequent understanding of freedom, that this society should not allow everyone access to its meetings. Members did not take this seriously. But to satisfy the curiosity of the public, it held a public meeting, and all who wished were invited. Speeches were delivered by various people, but the poet Jón Runólfsson was given the task of explaining the society’s intentions and goals and refuting the prejudices that had arisen. It was then clear to everyone that the magic was not terrible and the purpose praiseworthy. This meeting was held on May 12, 1883 and was considered the best entertainment. There is no mention of any further action by this society and it will probably be the same this winter, to stimulate interest in good books and their reading, rather than the other.”

One thing in Friðrik’s article about Björn is surprising, namely that English had become more natural to him than Icelandic in 1881 after only six years in North America. He was 10 years old when he came to the west and lived with his parents and siblings until 1879. Although the purpose of the society did not impress most Icelanders in Winnipeg, it is a remarkable example of integration into North American society. In the Icelandic countryside in Manitoba, N. Dakota and Minnesota, communication with residents of other nationalities was minimal, most of the farmers were Icelandic, so they used their mother tongue daily and had to speak very little English. It was even possible to go to the town (Winnipeg) from the countryside to pick up necessities, because around 1880 Icelandic merchants had arrived there and opened all kinds of shops. On the other hand, daily communication with the English-speaking majority of the city’s residents required some knowledge of English, and therefore Icelandic citizens emphasized mastery of the language. Parents in the city realized early on that the key to a bright future for their children in North America was a good command of English. It can be said that this is a turning point in the short history of Icelanders on the continent because no one dreams of an Icelandic colony anymore, somewhere remote in North America where all Icelandic westerners live. It can be said that in the future it would be possible to talk about civil society on the one hand and rural communities on the other. The new decade ended with a very clear difference between the two; Icelandic values gave way earlier to North Americans in Winnipeg than in the countryside, the western Icelandic language in the city showed clear signs of this, Western Icelanders had come a long way in coming of age. Perhaps the explanation for the sudden end of the literary society is that Björn Stefán moved from the city south to N. Dakota in 1882, where his parents and siblings had moved from Markland.

English version by Thor group.