Björn Sæmundsson came west alone to Canada in 1878, first living in Ontario, but moved from there to Minnesota. He was there for four years then moved north to Winnipeg.Quite a few young Icelanders had gathered in the city, some of them had just arrived from Iceland, and were having a hard time due to unemployment. The flooding of the Red River in 1882 as well as decreasing work on the Canada-Pacific railway put pressure on the population so in 1886 it was decided to examine the western part of the so-called Interlake area, i.e., the land west of New Iceland by Lake Winnipeg and the east side by Lake Manitoba. In Winnipeg, there was an association called Framfarafélag Íslendinga which was very concerned about the interests of Icelanders in Manitoba. Frímann B. Anderson was then the editor of Heimskringla and a great enthusiast for Icelandic settlement in the province and indeed the entire Canadian plain. He and the board of the Progressive Society (Framfarafélagsins) applied to the Canadian government for funding to finance an expedition west to what is now part of Saskatchewan. This is the Qu’Appelle Valley. Frímann and Björn Sæmundsson led the expedition, but in addition to them, Stefán Gunnarsson and a native guide joined the group. They headed west and explored the entire area of what is now Moosomin, west to Grenfell and south to Stoughton.

The map shows Winnipeg and a probable route from there west to the Qu’Appelle Valley. Pipestone is located in the southwestern corner of Manitoba..

The land was good there but almost everything had been taken, so they headed back and explored the area west and south of Pipestone. In this area, the soil is sandy and somewhat rocky, and they did not think it was good for them to grow grass. Friman liked it because he thought it would be easy to break ground there because there was no forest or brush there. Obviously, it was a struggle for Friman to find a large and fertile arable land, but Björn was different because he preferred cattle ranching to grain growing. They returned to Winnipeg without having found a suitable settlement site. It is worth noting that as the years passed, quite a few Icelanders settled in the area of Pipestone.

East Shore of Lake Manitoba – Second Expedition: Shortly after arriving in Winnipeg, another expedition was organized and this time northwest of Winnipeg. Again, Frímann was involved, and in an article he wrote in Heimskringla on November 4, 1886, it is written that Jón Júlíus, Káin’s brother, and a local guide went with him. Björn Sæmundsson is not mentioned in the article as one of the expedition members, but in various western sources the authors of articles about this expedition seem to be certain of Björn’s participation, among others. Jón Jónsson from Sledbrjót in Ólaf Þorgeirsson’s Almanak (1910) as well as Wilhelm Kristjánsson in the same publication. Skúli Sigfússon also mentions Björn in his article in Lundar’s Anniversary Book from 1947 when he talks about the excursion. It was beginning of fall when the trip took place on the 21st – 25th of October. A five-day expedition through a large area can hardly be considered extensive, but the area at the southern end of Grunnvatn (Shoal Lake) was particularly fascinating, where Frímann found the soil to be optimal. With this conclusion, they returned to Winnipeg, determined to further explore the country west of Shoal Lake. They went north on the 31st of October and went around the country in question in one day and liked it. There, forest belts, meadows, bogs and barren patches alternated. With this knowledge, the men returned to Winnipeg, but on May 24 the following year (1887), others went to the area and among them was Björn Sæmundsson, who took a good look around without taking land. Björn and wife Svava then settled in the Shoal Lake Settlement in 1891.

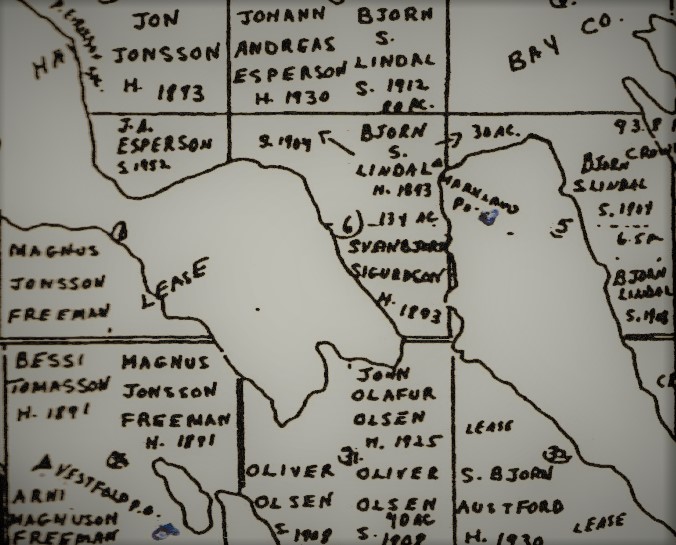

Map showing Björns land in 1891.

Grunnavatnsbyggð: Jón Jónsson from Sledbrjót wrote a section about the Shoal Lake Settlement in Manitoba and it appeared in Ólaf Þorgeirsson’s Almanak in Winnipeg in 1912. He got settlers to send him information about themselves and their first years in the West. Among them was Björn Sæmundsson, and among other things Jón says this about him: “Björn S Líndal was born in Gautshamri in Strandasysla in 1853. His father Sæmundur Björnsson, a farmer in Gautshamri, was the son of Björnson’s priest, Hjálmarsson in Tröllatunga. Björn’s father Hjálmar was also a priest in Tröllatunga. Björn Líndal’s mother was Guðrún Bjarnadóttir, a farmer in Þórustaðir in Bitra in Strandasysla. Björn Líndal has lived in Grunnavatnsbygð since he moved there and is one of the most valuable farmers there, he has a generous farm and a large business. Björn is a tall man of stature and masculine, princely and elegant in demeanor. He is intelligent and careful, steady and self-contained. He has been a mail clerk (Markland post office) for a long time, the treasurer of the school in Markland for between 10 and 20 years and has worked diligently on all the things he has allowed himself to do in social affairs.”

The last years in Iceland: “I grew up with my parents in Gautshamri, until my father died and then with my mother, until in 1872 I moved with her to Þamárvellir in Bitra, where she married Jón, farmer Bjarnason, who had lived there for a long time. In 1874, I became a freeman, at that time it cost 6 vats of knitwear to be a freeman in Iceland. I had a home in Þórustaðir in Bitra, because every free man had to have a home. I worked on common outdoor work in the summer, but on weaving in the winter. In the spring of 1875, I went to work as a laborer for Þorstein Jónsson and Guðrún Jónsdóttir, who lived in Broddanes in Strandasysla, and the following year I moved with them to Skriðunessenni in Strandasysla, where I was a worker until the fall of 1877, Dec. 9. Then it happened that my employers drowned. It happened on a sea trip, in the evening, from Broddanes to Skridunessenni. On the ship were my employers, Þorsteinn and Guðrún, and Matthías Jónsson, who then also lived at Enni, Bjarni, a teenager and Anna Bjarnadóttir, my employer’s maid. The ship ran aground and capsized. I knew how to swim and managed to get both of them to the keel of the ship. But then another wave came even more monstrous and turned around again. I reached back to the ship. The surf was terrible, and I didn’t see any of the people, except the girl. I was able to bring her to land, because it was just a short distance to the land. It can be said that these waves have pushed me to the West, because the following summer, 1878, I moved west across the ocean.”

The beginning overseas: “I spent the first summer in Ontario, but in the fall, I moved to Minneota, Minnesota. During the winter, I spent several months at school, where Eiríkur Bergmann was in charge. The lessons took place in a rooming house and the teacher was Norwegian. The following spring, I went to work on the railway, all my property was then worth 50 dollars. I stayed in the United States for 4 years, first doing common farm work and later in commercial work. There I learned many things that have been useful to me ever since; I have benefitted from my studies there and I have many good friends there whom I long to see. For example, about what newly arrived Icelanders had to live with, I remember that during my stay in Ontario, I had to work for 25 cents a day. The lack of language and lack of knowledge got the better of me. I couldn’t ask for better work, there was no one to go to with complaints. I had to take whatever I could get my hands on. Now, most of the immigrants move to prosperous friends or relatives and can live a good life with them, until something opens up for them – I moved to Winnipeg in the summer of 1882 and first worked there in trade with Helgi Jónsson, the editor of “Leifur”, then with an English merchant. In 1883 I married Svava Björnsdóttir, daughter of Kristjánsson (Skagfjörd), she was from Skagafjörður. Svava’s mother is Kristrún Sveinungadóttir. In 1883, I traveled west to the Pacific Ocean and with me on that trip were Haraldur Jóhannesson, Ólafsson of Húsavík and his dependents, Jón Jónsson, brother of Tómas, a lawyer in Winnipeg, and 1 teenage boy from Hrútafjörður. The idea was to look for a settlement west near the ocean. I went 200 miles north along Vancouver Island and around the mainland, which is now called Vancouver. I don’t think it could become an Icelandic colony in any context. But I felt I had to see. Not to be tricked like before, but to investigate whether there wasn’t a fertile and beautiful patch of land on the coast, suitable for a dwelling for me and other Icelanders who longed for the sea. I stayed for a while in Victoria City on the way home, then went from there to Washington State and Montana, because the C.P.R track was not then completed west. After that, I stayed in Winnipeg until I moved here. I am most clear about the implications of that in the article on the Swan Lake Settlement (Álftavatnbyggð)”.

English version by Thor group.

This sketch of settlers in the Shoal Lake Settlement (Grunnavatnsbyggð) shows Björn’s activities. He took land in 1893, then added land in 1904, 1908 and 1912. He actually owns a large part of the land around the lake that later got his name. On the map you can see the lands of Jón Jónsson (1893), Sveinbjörn Sigurðsson (1893), Magnús Jónsson Freeman (1891), Árni M. Fríman (1891) and Bessi Tómasson (1891).