The dark circle shows Jón’s land.

Jón Sigfússon was one of six people who set off from Winnipeg on May 24, 1887 northwest towards Lake Manitoba. These men were Björn S. Líndal, Árni M. Frímann (Árni Magnússon from Eyjafjörður), Ísleifur Guðjónsson, Jakob Crawford and Hinrik Jónsson. They explored the area by Grunnavatn (Shoal Lake) and Jón chose land there, the first of all Icelanders. He returned to Winnipeg and received permission from the authorities to settle on the settlement. This was the beginning of the so-called Lundar Settlement (Lundarbyggð).

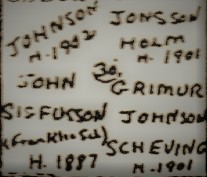

On this plan you can see the land division in Section 30. Jón’s land is marked to him as John Sigfusson and in brackets below that is the name of a school that was built there, called Franklin School. H. 1887 shows the year Jón took land here and received homestead rights. Others settle there later, compare years.

When it came time to write the story of the Lundar Settlement as a chapter in the fourth volume of the work “Saga Íslendingi í Vesturheimi”, the editor, Tryggvi J. Oleson, consulted Heimir Þorgrímsson. He was born in Akureyri but moved west at the age of 18 and spent a lot of time in the Lundar Settlement, lived in Lundar for years. Heimir took on the task as he had met many of the inhabitants of the settlement, traveled far and wide around the countryside and collected material. In the preface, Heimir says: “This story is mainly based on the sources that appeared in Ólaf S. Thorgeirsson’s Almanak and the History of Álftavatn – og Grunnavatnsbyggði (History of Swan Lake and Shoal Lake Settlements), and on the personal experiences that I myself have of these rural communities . It doesn’t occur to me to think that everything is correct, although I have tried to the best of my ability to gather all the information I can get my hands on. In addition, Tryggvi J. Oleson, who oversees this work, has been my second hand and researched and compared various sources, especially those that can only be found in western Icelandic newspapers and magazines.” It contains countless episodes and stories about settlers and their settlements. Many contributed to work in the Almanak by editors and publishers, and one of them was Jón Jónsson, often referred to from Sleðbrjót, who wrote an episode about the Icelanders east of Lake Manitoba and talks about Jón Sigfússon. Here is a chapter about Jón that Heimir put together and is somewhat based on the story of Jón from Sleðbrjót, who went west across the ocean in 1903 and settled in the Lundar Settlement for the first time.

“Jón Sigfússon was born on October 2, 1862 at Nes in Norðfjörður in Suður-Múlasylsa. His parents were Sigfús Sveinsson and Ólöf Sveinsdóttir, who lived on Nes all their farming lives, about or over 30 years, until they moved to the West in 1887. When Jón was 16 years old, he started working for Sveinbjörn Jakobsen, a merchant in Líverpól in Seyðisfjörður. After two years there, he returned home to his parents. But after a year, he worked for merchant Jón Magnússon again as a shopkeeper in Eskifjörður. But after 1 year he moved back home to his parents. In the spring of 1883, he set off for America, alone. ” “I went there”, says Jón, “to seek my fortune”. He travelled on a coal ship from Seyðisfjörður to Scotland. He arrived in Winnipeg on June 4 and had then been 6 weeks on the way from Iceland. Back then there was very little work to be had in Winnipeg. “But since I made it here”, says Jón, “then I had to work”. So he got a job building railways and worked at it during the summer and until the following winter. In the month of January, he returned to Winnipeg and then had more than 200 dollars in his account. He spent the rest of the winter studying English with B. L. Baldwinson (that’s how Baldvin Lárus Baldvinsson spelled his name in the West), the current editor of Heimskringla, who by then oftrn gave advice to young men. In the summer of 1884, Jón married Anna Soffía Kristjánsdóttir (born in Eyjafjörður). He then moved that summer to New Iceland and had the intention of starting farming there. He stayed there the following winter, but felt ill at ease ; he was then almost penniless, and says he saw no future for himself. He therefore moved to Winnipeg in the spring of 1885 and stayed there for a year.”

Future Area: “As already mentioned, about that time a railroad had begun to be laid northwest from Winnipeg to the east of Lake Manitoba, and it was planned that that railroad would be laid all the way to Hudson Bay. Jón, like others, thought it was possible to look for a home along this road near Winnipeg. Jón considers his reasons why he followed this advice: “Homestead lands around Winnipeg were then very few unoccupied. But I was already confident that Winnipeg would, in time, become the main market of the Northwest*. In those years, wheat was severely damaged by frosts in the Northwest; I thought it would be better to practice livestock raising.” When Jón came back to Winnipeg, he bought himself a 4-year-old ox, and after a short time he set off again for his settlement, to build a shelter for himself and his family and because he was also expecting his parents and brother from home in Iceland. In July during the summer, he moved finally from Winnipeg with his wife and two daughters, Kristjana, 3 years old, and Júlíana, 3 weeks old; then he was also accompanied by his parents and his brother Skúli, then 17 years old. Throughout his journey he had used one wagon and two oxen. But to transport the family he hired a man who had horses and a carriage. There also came his companions with their families, Árni Freeman and Ísleifur, who were mentioned earlier. A little later there came Jón Sigurðsson, H. Halldórsson (This was Halldór Halldórsson from Gili in Bolungarvík in Ísafjarðarsýsla: insert JÞ) and Jón Metúsalemsson and others. Jón’s assets when he started the farm were, according to him, the following: 3 cows, 1 calf, 2 oxen and a wagon. Jón acquired hay for these animals during the summer in the company of his English neighbor, and then he realized that he had mastered the English language, and that made it easier for him than others to communicate with people from here. Jón gave the oxen to his English neighbor to transport his luggage from Winnipeg, but the wagon was in a poor condition so the oxen got sick from being pushed too hard, they were never able to work again.”

Wildfires: Wildfires were quite common in North America during the settlement years. Some years are quite hot and droughts are extreme. There was a lot of fuel for fire everywhere, because grasses and various shrubs grew on the plain, which withered as the summer wore on. Usually these fires started when lightning struck. This was made clear to the settlers everywhere and how best to protect themselves from these fires. People had to burn a wide circle all around their houses, carefully so that when the raging fire got there, it died out or went past the farm. Icelanders still often lost hay, sometimes houses, and even animals during the first settlement years. Now the continuation of the story of Jón Sigfússon :(JÞ)

“After the mowing, Jón burned around his home, according to the custom of the settlers, to prevent wildfires; then he set off for Winnipeg to look for work as a shopkeeper and in that way earn money for household needs. But a little later the news reached him in Winnipeg that his barn and hay had all burned to the ground in a prairie fire. He set off for home and started his journey from Winnipeg at 9 in the morning. He was on foot and walking along the railway station. About this trip, he had the following words: “When I had walked 7 or 8 miles, I could hardly bear to step down, because I was wearing hard workman’s shoes, which had spikes sticking out here and there. I still continued without rest and at 7 in the evening I had come 45 miles, and then had about 30 miles to go. I still continued the next morning and got home at 2 that day”. When Jón came home, he began to scythe the new-born grass. The hay he got, was very poor, but he still managed to stow away enough for the next winter. The two cows gave some milk, and Halldór Halldórsson took them to feed, and the milk from them had to pay for the feed. With the help of his neighbors, English and Icelandic, Jón´s cows lived through the winter. The following spring, Jón bought 1 cow and 3 winterlings, with money that his parents brought from home; he now had 4 cows. But then new troubles befell him. He needed to go to Winnipeg on a business trip, to get provisions for the home. But now he didn’t have any transport, except the aging oxen mentioned above. Yet he set off with some of his English neighbors. Little progress was made but it happened, fortunately, that one of his companions had 2 oxen, which he was willing to sell if he could get money for them right away. The oxen were very well trained and the greatest asset of the farmer. Jón needed the oxen and the sale was done. Jón set the conditions of purchase, that if he did not bring the money to a certain place in Winnipeg after he had spent half a day in the city, then he had to return the oxen. The seller agreed to this and Jón left his sick oxen in the middle of the road. The companions kept on their way. Jón made the payment at the specified place and time and paid for the oxen in full. This is what Jón says about this. ”When I came to Winnipeg, I had no idea how I could get this 100 dollars. At the time, I knew few people in town and did not expect to be successful in getting a loan. I met with the merchant, Árni Friðriksson, and told him my situation. He readily loaned me 100 dollars without saying a word for six months. Now I felt bad about being in debt for a long time, so I sold 3 cows (I had 1 left) to be able to pay for the oxen. Then I gave Árni the money on time with no interest added. I hope he gets his rent paid when he needs it most”. ( Árni owned properties in Winnipeg he rented J.Th.)

Better times: It was then that Jón’s situation started to improve. Now (1914) he is considered the wealthiest Icelander in the settlement, he has often fed about 300 cattle, which he has owned…Jón now has about 12 farms, which he uses almost all every year for haymaking and cattle drives.”

* The area west of Manitoba west to the Rockies was called the Northwest until the provinces of Saskatchewan and Alberta were created in the early 1900s. Today, the Northwest is the area north of Saskatchewan, Alberta and part of British Columbia. To the west is the Yukon and to the east is Nunavut!

English version by Thor group.