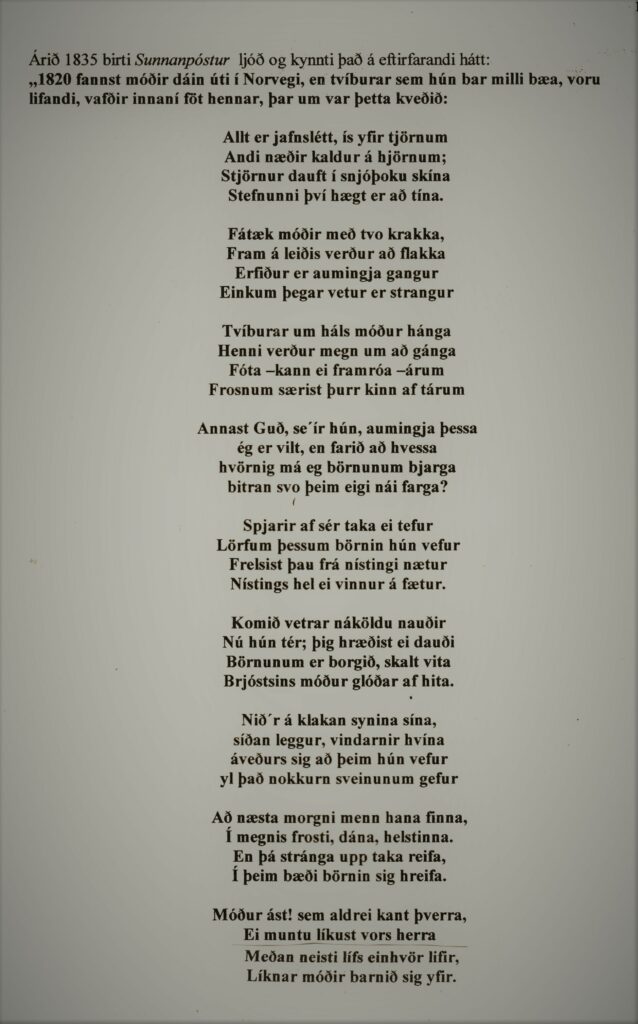

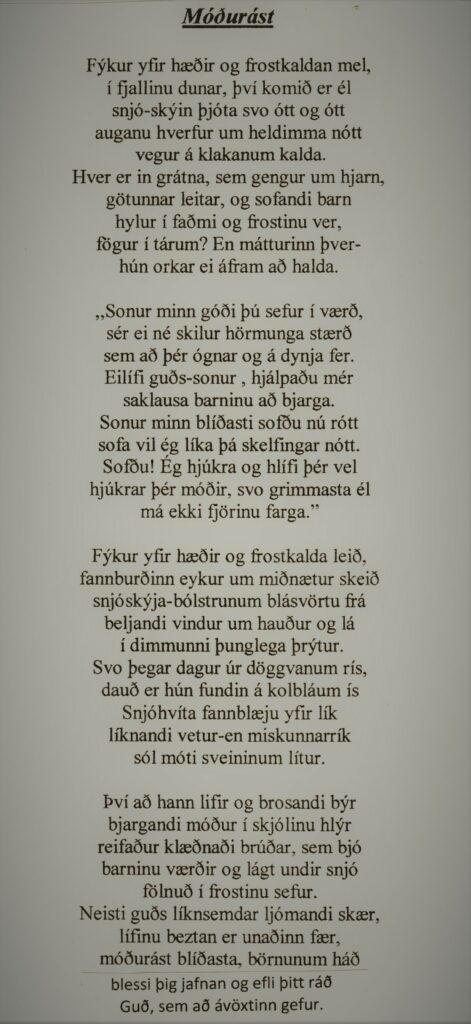

Jónas Hallgrímsson wrote Móðurást in 1837 at home in Iceland. He wrote his associates in Fjölni and sent them his poem. A fragment of the poet’s letter found its way onto the pages of the newspaper and reads as follows: “Since I’ve started mentioning the poems in Sunnanpóst, I’d better tell you a story about me and one of them. I brought it up again the other day. It’s called Móðurást and the occasion is, as you remember, that a beggar woman in Norway was caught in a blizzard, but her two children, whom she had with her, were found alive because the woman wrapped them in her clothes and saved them with her own death. It is quickly seen that this event is a good source of material if a poet were to go; and that has been felt by the person who wrote the poem in the Sunnanpóst, even though he managed poorly to produce it. He did not warn himself that it will be disgusting and upset the sense of beauty of everyone who has such a feeling when he describes the woman, how she was thin and homely, and how she sits and she removed her tattered clothes, one after another, so that she is left naked in front of the reader’s eyes – as well as other little things, for example, “fóta kann ei fram róa árum (foot can’t row forward)” etc. I am not a poet, as you know, and I did not send you my poem in order that you will think that something will come of it; but so you see what I wish the other man had avoided saying; because I have taken it upon myself to ignore everything that I disliked most about his poetry”. (From Jónas Hallgrímsson’s Poetry Collection) The author of the poem in Sunnanpóst is unknown, only the letters A.H. follow the poem.

Jónas Hallgrímsson’s Móðurást certainly moved the hearts of the country’s people, everyone is familiar with blinding storms and cold hail, many “have disappeared on cold and frozen nights” (“hvarf auga um heldimma nótt vegur á klakanum kalda”). And surely the poem has often come to the mind of many a westerner in the dead of winter on the icy plains of North Dakota and Manitoba. With this in mind, it is appropriate to hear more about Guðrún Einarsdóttir, who came west with her two children to New Iceland in 1878. Father of Guðrúns children was Sigmundur Matthíasson, who was born in Loðmundarfjörður on September 7, 1841. His parents’ fortunes improved little after the birth, he actually lived with them for nine years, but then the child’s life took an exceptional turn because he moved from one rural community to another, either as a foster boy or farmhand. In 1868, he goes to Hamragerði in Eiðaþinghá, where Guðrún Einarsdóttir is a maid. Perhaps she had something to do with the fact that he stayed in Hamragerði for five years and on October 28, 1872, Guðrún gave birth to a daughter, Borghildur, and on October 29, 1874, Vilhjálmur was born. Let’s pause here in the narrative because the reader may think that the parents’ happiness was great and Sigmund undoubtedly loved Guðrún and the two children. But he found it extremely difficult to keep his love life within decent limits. In the years 1872-1877, he was not married at all, and when he decided to marry another woman and got married in early 1878, Guðrúna had had enough. On June 17, the same year, she left Iceland and sailed west to Canada with their two children and set foot in New Iceland. She stayed there with her half-brother, Metúsalem Oleson for the next few years, but in the summer of 1883, she went south to Mountain, N. Dakota. She had friends and acquaintances there, it was Christmas and the New Year. In the new year, Guðrún wanted to explore various possibilities in the Icelandic settlement, e.g. in Garðar, as more friends were living there. At the beginning of March 1884, she thought of a move, felt that she was a burden to the people she lived with in Mountain, and decided to go to friends in Garðar. The entire household dissuaded her from planning this trip with her two children, eight-year-old Borghildur and six-year-old Vilhjálmur. At this time of the year, usually all kinds of weather are expected in the plains, it is very common for months of calm in the air to be broken by powerful storms, sometimes such disasters continue from time to time until March, but in the end, winter gives way to spring and the gloom subsides. Margrét J. Benedictsson wrote a chapter about Icelanders on the Pacific Coast in the Almanak, and in one of them in 1929 there is the following description of Guðrún’s fate: “The conditions were bad, – snow on the ground and slush. The people in Mountain wanted her to wait for the next day, but Guðrún didn’t want that, and what a day would be her last. This distance is estimated to be about 6 miles. People think that she took the wrong path when it was getting dark. She had told the children to wait for her while she went back to find the right way, warned them to be careful and not to lie down, whatever happened, until she came back, or someone found them. People think from this that she knew that her days were numbered, as she stayed out – she died that night. A traveler had seen their journey on a different path than expected, and he told about it the day after. The children had also seen this man and called to him, but he did not hear them. The next day they went to search, and they were all found, Guðrún dead, but the children, who had obeyed their mother and had been walking back and forth during the night, were alive with little or no injury. It’s almost a miracle that they survived the night. Some say that Guðrún took off what she could of her clothes and left it on the children, but she herself had walked a short distance from there, laid down there and fell asleep.”

English version by Thor group