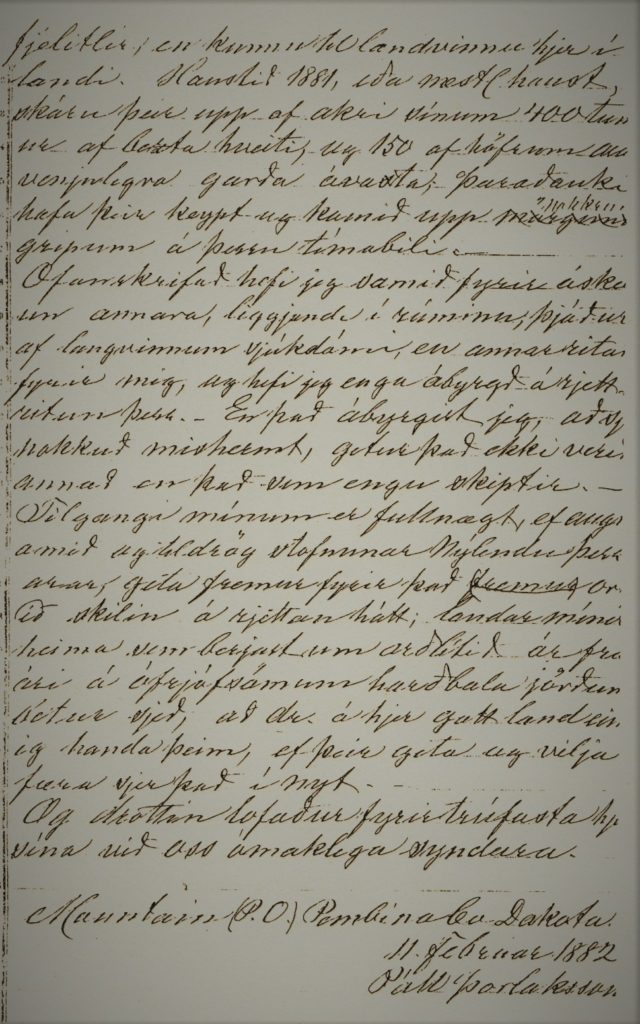

The above is the last page of Rev. Paul Thorlakson’s account, written down by his father and completed February 11, 1882. At the bottom is Rev. Thorlakson’s signature; three weeks later he was dead. Photo: PIB.

Björn Pétursson from Eiðar in S. Múlasýsla emigrated to Manitoba in 1876 and settled in New Iceland that same year. There he became acquainted with Rev. Páll Þorláksson (Paul Thorlakson) and followed his advice and emigrated to N. Dakota in 1880. Soon he became involved in the development of a new Icelandic settlement and apparently became a good friend of the pastor. It is unknown whether Rev. Thorlakson had introduced Björn to the idea of writing an essay on the economic situation of their fellow-countrymen and other ethnic groups in the West, but the pastor strove for providing the Icelandic Nation with useful information on the situation of Icelanders in North America. Björn’s essay was complete in early 1882 and he read it to the Rev. Thorlakson on his deathbed. The pastor was content as he himself had considered writing an account on the history of Icelandic settlement in N. Dakota. In her book Saga Íslendinga í N. Dakota, published in 1926, Þórstína Þorleifsdóttir mentions this event and says Rev. Níels Steingrímur Þorláksson had given her permission to publish Rev. Paul Thorlakson´s account. Þorlákur Gunnar Jónsson wrote a brief introduction and explains the reasons. (J.TH)

The following is a depsition which the late Pastor Paul Thorlaksson dictated from his deathbed at Mountain, North Dakota, in 1882 at the request of his friend, the late Björn Pétursson. It was agreed by these two men that Björn should have Paul’s statement printed together with his own recently compiled account of the circumstances and economic conditions of immigrant groups from Iceland and elsewhere who had settled in America. Björn’s essay was printed and sent to Iceland, but Paul’s statement was not included. The individual who took down Paul’s words (i.e., T.G.J., his father) preserved the manuscript and has had it in safekeeping for the past eighteen years.

Mountain, N. Dakota, in April 1900.

Thorlakur Gunnar Jónsson.

A brief explanation is useful here to explain why Paul Thorlaksson became involved in New Iceland. Sigtryggur Jónasson brought two large groups from Iceland to Winnipeg in the summer of 1876, around 1200 immigrants. All were heading to New Iceland. “The impending arrival of over 1200 newcomers to the exclusively Icelandic colony on the western shore of Lake Winnipeg was given extensive coverage in the Norwegian-American press. The committee on home missions of the Norwegian Synod requested Paul Thorlaksson to visit New Iceland that summer to minister to the people there and offer to serve as their pastor for a few months each year. Leaving Shawano (Wisconsin) on August 4, 1876, Paul no doubt paid visits to a few friends on his way west to Fisher’s Landing where he boarded a stern-wheeler for a journey of several days down the Red River to Winnipeg. A few years later, Paul wrote about an incident that occurred on the boat:” (PIP p.120)

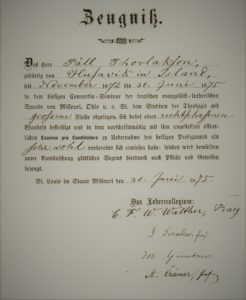

Paul Thorlaksson’s Graduation Diploma. Paul graduated in Theology from Concordia Seminary, St. Louis, Missouri in 1875. Photo: PI

“Railway had yet to reach north to the border so I had to travel on a steamboat down the Red River the 450-500 miles north to Winnipeg, Manitoba. The captain told me he had recently taken a number of Icelanders to Winnipeg (no doubt a portion of the group escorted by Sigtryggur Jónasson), and he lamented the fact that so many promising people were directed past the fertile, still unsettled, tracts on both sides of the Red River (south of the international boundary) into a region farther north, which, according to him, was uninhabitable. He wanted me to try to turn them back. I explained to him, however, that under the circumstances there was nothing I could do. These people had been promised substantial assistance from the Canadian Government to settle in New Iceland, and since I was not personally familiar with that area, I was in no position to assume it was unsuitable for settlement. – Paul was in New Iceland during the winter and witnessed tremendous hardships throughout the colony and sensed that many began to lose faith that their circumstances would improve in the near future. Meetings were held in the Árnes district where settlers discussed ways to improve conditions. Several suggestions were discussed all of which ended the same way; there was no way for improvements. So, meetings concluded, although many disliked it, that they would have to move away. Paul said: “It was obvious that if the government agents and Framfari (Newspaper in New Iceland) were to have their way, if matters were permitted to follow their own course and if no attempt were made to find a more promising location to which people from New Iceland and immigrants from Iceland could be directed, increasing numbers of them would have to suffer similar hardships. I therefore determined to seek a more advantageous location that spring, even though there appeared to be little likelihood that many could derive advantage from it on account of their extreme poverty.”

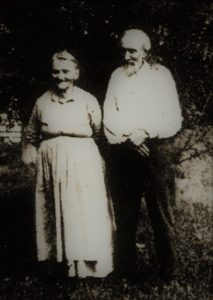

Mr. and Mrs. Butler Olson. They were pioneers on the plains west of Cavalier. They assisted Icelandic settlers in the area who later moved to Brown Settlement in Manitoba.

Exploration: “A few men decided to accompany me: Jóhann Hallsson with his son Gunnar and Magnús Stefánsson from Gimli. In Winnipeg we were joined by two others, Sigurður Josúa Björnsson and Árni Thorlaksson (No relations to Paul, Ins. J.TH). Before leaving Gimli the intention uppermost in our minds was to begin our search for land only after travelling as far as the Icelandic settlement in Lyon County, Minnesota. During our sojourn in Winnipeg, Magnús Stefánsson fell into conversation with a newspaper editor who claimed to be familiar with areas of northern Dakota (Territory) and declared that he could not recommend to us a more promising district than that in the vicinity of the so-called Pembina Hills. This man, who appeared to be genuinely moved by the hardships of the colonists at New Iceland, was desirous of discussing the Pembina district with me. At first I thought he might be a land speculator owning tracts in the districts and for that reason eager to see it settled as soon as possible. I saw no reason to discard his advice altogether, so my companions and I decided to stop off at Pembina, just south of the border, and continue westward from there to the Pembina Hills. That would probably have been around the middle of April. The weather was exceptionally mild. We disembarked at Pembina late in the afternoon and put up for the night at a modest lodging house on the riverbank. (In those days there were but few buildings there, and even fewer substantial ones) The next morning we set out on foot west across the prairie along the south bank of the so-called Tongue River, which flows east from the Pembina Hills. There were no houses to be seen on the prairie, only the odd one here and there on the edge of the forest along the riverbank. We stopped at several and made inquiries about the area. Most of the people to whom we spoke could provide little information except about their own homesteads and those of their neighbors, but they were well pleased with their farms. A few of them, however, were of the opinion there was arable land to the west, in the vicinity of the hills. We obtained our most valuable information from a well-to-do German farmer names John Bertel (properly Bechtel), at whose home we stayed overnight, near Cavalier Post Office, 24 miles southwest of Pembina. He had been farming there for the past two years. (At that time this was just about the extreme limit of the Tongue River settlement, with nothing beyond but wilderness.) We set out from Cavalier the next morning, continuing in the same direction out into the wilderness. Now the forest along the river became increasingly dense and spread out, the terrain more elevated and less fertile. At times we followed the north bank of the river, at others the south, through a deep valley, until we came in sight of the hills. Then all at once the land began to decline. As far as the eye could see, there lay before us to the south and west green plains with belts of woodland. This land impressed us as being what in Iceland we call sveitalegt – suitable for farming. Where the terrain began to slope down again, we found the same rich soil we had previously seen on the grassy plains. After resting here a while, we decided to turn back, for it was getting late and we were very tired. At the same time, however, we decided that my companions should investigate more thoroughly this tract which lay before us while I followed my original plan to inspect land elsewhere in Dakota and Minnesota, 300 miles farther south. Even then I began to think we could not select a better site for our settlement than that area here, east of the hills, even though it was still distant from a market town. Provided the soil throughout the district were as rich as that we had already seen, the extensive forested tracts constituted yet another point in its favor. The reader will now have surmised that we just obtained our first glimpse – albeit from a distance- of the region known as the Icelandic settlement in Dakota, already the home of more than 600 Icelanders, many of whom own beautiful farms and fine livestock. We spent the next night at the home of B. Olsen, a Norwegian, whose farm was located in the wooded area southwest of Cavalier. The only settler of that nationality, he had arrived not long before with his wife and children. He treated us as though we were his brothers and bade us welcome to his neighbourhood.”

Jóhann Hallsson. The area around his homestead was named after him. Photo: SÍND.

The situation in New Iceland: “Six months later, while returning from Minnesota and Wisconsin to become resident pastor to the congregations which had been organized under my charge the previous winter in New Iceland, I detoured to the west to visit my companions in the Pembina Hills. Two of them had homesteaded in the immediate vicinity of Olsen’s farm, but Jóhann Hallsson and his son, together with Gísli Egilsson, Jóhann’s son-in-law, who had joined them, had settled a short distance to the west of the place we had stopped the previous spring. I gave them a detailed account of my search for land farther south, adding that there was no doubt in my mind that we should choose a site for the settlement here in the Pembina district in preference to Minnesota. There were two principal reasons for this decision: first, ease of access for the people of New Iceland, and second, the presence of convenient and extensive tracts of timber. Farther south there were only grassy plains, with no forested tracts at all. Meanwhile there were several other developments. After we separated the previous spring, it did not take Jóhann Hallsson long to make up his mind to return to New Iceland to fetch his family and possessions. This aroused no little consternation in New Iceland. The government agents ridiculed the idea in the English papers and Framfari , spoke of pressure and trickery on my part, and called my followers the most feckless people in New Iceland, parasites who clung to me for the gifts and assistance they hoped to obtain, and so on, adding that fortunately, so far as they and others could ascertain, there were but few such individuals, and the misbegotten undertaking would soon collapse. They did all in their power to ruin Jóhann. Not only did they strip him of unused portion of his government loan – which was, moreover, irregular – but also confiscated cattle he had purchased with his own funds. Framfari prevailed on two men who had made a quick trip through the Pembina district in the summer to assert that they had found nothing there except land which was uninhabitable or virtually so.

The winter wore on. Men began to devote thought to the question of moving and to discuss it, at first only in private conversations. As its frequently the case, opinions differed widely. Some people set themselves to composing patriotic songs about New Iceland. Framfari published them, but they seem to have had little effect. Men became increasingly convinced that the future of New Iceland was anything but promising. It was sad, on the other hand, to contemplate abandoning one’s home, the fruits of his labour over several years, his government loan, half-finished churches, the graves of dear ones, and then have to begin anew in another wilderness. The Chairman of the Colony Council, Ólafur Ólafsson, eventually called a meeting to discuss the matter. It was attended, however, by comparatively few men. I expressed the opinion there that if men had valid reason to expect they would be able to make a decent living for themselves and their families in New Iceland and live together like civilized Christians, it was no doubt best for them to remain there. On the other hand, I said, if they had no reason to believe it, then for their own sake and that of their children, it was their duty to seek more propitious location without delay and without contravening the law. I told them what I knew of Dakota. Just before the meeting was adjourned it was decided that Ólafur Ólafsson and I should be entrusted with preparing an account of conditions at New Iceland as well as a petition to the government with regard to moving out of the colony, the petition to be circulated for the signitures of those desiring to leave.

Midwinter came and passed. Increasing numbers of men made the tiring journey to inspect land south of the border. Among them was Jón Bergmann, who subsequently wrote one of the most cogent and detailed accounts to reach New Iceland. His letter aroused considerable attention, for he was well known for prudence in word and deed. At this juncture it should be mentioned that the distance from Gimli in New Iceland to Pembina is 120 miles. It is another 40 miles from Pembina west to the hills. Lack of funds compelled most of the men to cover this distance on foot, but one could not possibly imagine how the women, the children and the elderly could make the journey without assistance. It was, however, imperative not to draw back; the move was urgent, but it met strong oppositions from the government agents and their friends. (Here Paul refers to Sigtryggur Jónasson and John Taylor. Ins. J.Th) I discussed the matter with my congregations, inquiring whether it was their firm desire to move south. By and large people favoured this course of action, but were hesitant to embark on such undertaking. By this time (i.e. the early spring of 1879) Ólafur and I had completed the petition to the Canadian government, obtained the signatures of 130 heads of families. translated the document and forwarded it to the government. Based on hearsay from the agents, the reply of the authorities is too well known to be repeated here. Our only thought was to save ourselves and those who wanted to be rescued, to make our way out of the mire on to dry land. Summer came; people gradually surmounted their difficulties, provided in response to my pleas, so that by autumn of 1879 about fifty families had settled on choice tracts east of the Pembina Hills.”

A New Start: “That summer (1879) I moved into the district to stay, homesteaded in what is now the center of the settlement and, with the help of my countrymen, built myself a house. At that time my health was already seriously impaired, and I was far from fit to occupy the position I held, but much of what had to be accomplished was still undone. The foundation of the settlement had been laid, to be sure, but destitute people, beset by hardships far out in the wilderness, had a long winter to face. Some lost heart, others began to predict calamity and talked of returning to New Iceland. I had begun this undertaking in the Lord’s name and continued steadfast in my faith that He would bring it to a happy fruition. My trust was not in vain. The winter passed, one of the most severe ever experienced in these parts. It sometimes happened that several families were without food at the same time. Thanks, however, to donations made now and again by Norwegians in the Synod and to loans from farmers in the vicinity, it was always possible to avert disaster. I assumed the responsibility myself of repaying the loans when they came due. Inasmuch as possible everything was used sparingly and, in all justice, it may be said that people were frugal and careful that winter.

The reader must bear in mind that most of the families had not yet reaped a crop of any kind; now it was imperative that they cultivate their land and make hay in preparation for the coming summer, but in all truth, there was neither seed grain nor sufficient food the spring of 1880. I therefore prevailed upon my brother Haraldur, who had come from Wisconsin the year before with a considerable quantity of livestock, to join me in mortgaging his stock for seed, food and a supply of the most essential agricultural implements. Although in Minnesota for medical treatment at that time, I constantly had news of what was happening farther north, in both Dakota and New Iceland. Among other things I heard that my detractors in New Iceland were employing every conceivable means to deter the Norwegians from rendering continued assistance to my undertaking. To that end, a meeting had been called, open to all residents of the colony, where it had been declared that my actions were detrimental and a disgrace to the Icelanders; that loyalty to the colony demanded an investigation of the matter so that disgrace might fall only on those who deserved it, while the others might be exonerated with their honour and reputation unsullied.” …While in Minnesota, Paul received a letter in Norwegian, written in New Iceland. “The writer of the letter declared categorically that my undertaking was entirely unnecessary; New Iceland offered splendid prospects for the future and the people there were highly satisfied with their conditions. Icelanders were reported to be enraged over my activities. The accounts I had written from New Iceland were declared to be false and there were said to be other misstatements as well, obviously calculated to play on the sympathy of generous people, and so on.”

Pastor’s Reaction: All considered, I realized that in order to counteract the effect of the article when it was published, I had to take two actions: first, publish in the paper a brief reply to the article and second, undertake a journey among the Norwegians in Minnesota, explain the situation to them and urge them to lend prompt assistance. I began by approaching the merchant with whom I was staying, showed him the letter and persuaded him to lend our settlement 100 barrels of wheat flour for one year and 40 head of cattle for three years, all at 10% interest. I thereupon wrote to the management of the St. Paul, Minneapolis and Manitoba Railway Company in St. Paul, pleading with them to transport the cattle and flour to Pembina, a distance of 400 miles, free of charge. Otherwise, it would have cost me three hundred dollars. The company lost no time in acceding to my request. The flour reached Pembina, but only 25 head of cattle were sent at that time. The news quickly spread through the settlement; people’s hopes were revived, but even with this assistance there were still too many in dire need. The merchant shook his head at my audacity, asserting that he did all this on my account. I then asked him to lend me a horse so that I might ride out to visit the Norwegian farmers in the neighbourhood and persuade them to lend me an equal amount of cattle. He laughed but lent me the horse. Two weeks later I had 34 head of cattle driven into the merchant´s paddock, to which he added nine of his own. Once more I wrote to the railway company at St. Paul, informed them of what the farmers had done, and inquired what the shipping charge would be now. They replied at once, stating they would also transport these cattle free of charge. They would not, however, commit themselves to any additional promises. Together with two Norwegian cattlemen, I accompanied the cattle north to Pembina, continuing from there to my home. The people were clearly jubilant over this acquisition, which soon disappeared like a drop in the ocean, for now the population had been increased by a number of destitute people from New Iceland.

I obtained this loan from the farmers on the same terms as the previous one from the merchant, except that the farmers set a lower evaluation on their livestock. But in order to utilize a portion of the cattle as an installment on debts incurred earlier, which had now become due, and which I was obligated to pay immediately on the settlement’s behalf, I was constrained to re-evaluate the cattle on the basis of the figures set by the merchant, for I had obtained a cash loan of only two hundred dollars. Shortly after my return I called a meeting, explained to the people what I had done, and sought additional information as to their circumstances in general and their expectations of getting along through the coming winter, for if they could manage that, I considered the settlement be on firm footing. It then became evident that our efforts to date would not suffice. I volunteered to travel some two hundred miles south into Minnesota in an endeavour to borrow more cattle from the Norwegian congregations there. This proposal was well received. Men promised to do all in their power to obtain work and it is safe to say that few, if any, shirked since they came here. In July I journeyed south again, although only half the distance I had covered before. I either rode or drove through the Norwegian settlements and was well received everywhere, especially by the rural pastors, who either lent me a mount or drove me about as a favour; they invariably accompanied me and nobly supported my case among the members of their congregations. After nearly two months of this type of travel, I had been promised 85 head of cattle, young and old, together with 65 ewes and a small amount of cash. Then, at my behest, two men and two boys from our settlement came to join me. With the aid of the Norwegians we gathered together all the livestock, drove it north, and arrived home with virtually all of it safe and sound on October 2nd.

I then appointed a committee of three men to place a fair value on this stock, and on that basis we lent most of it in the district with the understanding it would be paid for in three years, one third annually, interest free. Some of the cattle were sold to satisfy the debt the settlement I had incurred for food. I obtained some of this livestock in the form of a three-year, interest-free loan, the rest as an outright gift, but in order to repay the loans to the settlement which I had guaranteed, I had to sell all the cattle, and even then was barely able to satisfy the settlement’s obligations. I could mention here that, unfortunately, there are some in our settlement who find it beyond their comprehension how I could have obtained some of the livestock as a gift and yet have good reason for selling all of it upon its arrival here. No goal would be achieved, however, and no significant charitable work brought to fruition if one held back through fear of being misunderstood and suspected of unworthy motives by some people, indeed, the very ones who benefitted the most. At last there appeared to be a good reason to believe our settlement would survive the coming winter, for several farmers had a fair crop that autumn (1880) and our community had been augmented, moreover, by the arrival of a number of self-supporting individuals and even men of some means from Lyon County, Minnesota, and Shawano County, Wisconsin. Quite a few of the settlers who had hired out as harvest hands returned to their homes with appreciable sums of money, and were also joined by people with means of their own who came from Winnipeg and other places in Manitoba.

The following years: The situation in New Iceland was now such that even some of those who had praised that district to the skies the previous spring were now discouraged and longed more than ever to leave, for shortly after the above-mentioned article appeared in the papers, Lake Winnipeg overflowed and inundated a large part of the colony. The eyes of the shortsighted men were opened and even they now admitted the much-vaunted New Iceland was too swampy for large settlements to prosper there. That flood was followed by others. The authors of the famous document refrained from sending to the papers fresh reports on the delightful conditions prevailing in New Iceland as well as other matters they had contemplated with unjustified optimism. More than a year has elapsed since then and it is remarkable how much progress our settlement has made in that time. It is improbable that anyone familiar with conditions here can doubt that within a few years the district will be flourishing. Not least on the grounds for that expectation is the reported decision of a prospering railway company to extend its line through the settlement, east of the hills. Now people of other national origins are vying to settle here. Everyone admires the beauty and richness of the land and the advantages of having sufficient wooded tracts, grassland and excellent water flowing from the hills. Consequently, nearly all the tracts have been claimed. As of now, the settlement can hardly be extended except westward to the hills, which have not yet been surveyed. Thus far we have explored these hills only on a small scale. For my part, for instance, I have travelled no farther than three or four miles west into them. The hillsides and dales in the eastern portion are covered with forests and groves of willows, above which there extends an undulating grassy plain as far as the eye can see. Several families, Icelanders included, have already homesteaded there and are well pleased with the quality of the soil. What we refer to as our settlement is a strip 16 miles long and 6-12 miles wide. Men who have explored farther west report lakes full of fish, forests and the same excellence of soil far west of the hills and, still farther west more hills and mountains, surpassing these in scenic beauty and other respects as well. For the time being, homesteading is not permitted more than 24 miles west from the edge of the hills, but as is customary, permission will no doubt be granted by the United States Government as migration proceeds farther west.

Sigurjón Sveinsson

Benedikt Jóhannesson Photo: SÍND

Conclusion: I expect that by this time the reader will think me verbose. Nevertheless, I should like to mention a small detail which may serve to give my countrymen a clear idea of how quickly a diligent farmer can get ahead here. Two young bachelors, Sigurjón Sveinsson and Benedikt Jóhannesson, came here from Wisconsin the summer of 1879 and homesteaded side by side, building for themselves rather rough shacks. They went into partnership, taking turns staying home and hiring out. They had, to be sure, little cash, but a sound knowledge of farming. The autumn of 1881, or perhaps that of 1880, they harvested from their tracts 400 barrels of the finest quality wheat flour and 150 of oats. This was in addition to the usual garden produce. During this period, they also purchased livestock and began building up a herd of cattle. Confined to my bed, suffering from a long illness, I have put the foregoing together at the request of others, but someone else has transcribed it. I cannot take the responsibility for its being letter perfect, but I do guarantee that if anything is misstated, it can only be a matter of no consequence. If my account contributes to a better understanding of our settlement and the reasons for establishing it, my purpose will have been realized. My countrymen at home, who struggled from year to year on hard, barren soil, can comprehend more fully that the Lord has provided good land here, for them as well, if they have the ability and the will to take advantage of it. And so may the Lord be praised for His never-failing help to us, undeserving sinners we be.

Mountain Post Office, Pembina Co., Dakota, February 11, 1882

Páll Þorláksson (Paul Thorlaksson)

For Further Understanding: In order to better understand the controversies between Rev. Páll Þorláksson and the leaders of the settlers in New Iceland, interesting articles in Framfari by Sigtryggur Jónasson, editor Halldór Briem, Rev. Jón Bjarnason and others should be mentioned. One of the main reasons for the establishing the colony New Iceland, remote on the western bank of Lake Winnipeg was first and foremost to preserve Icelandic heritage in North America. Isolated, outside the growing Canadian community an independent, Icelandic community was established, free of any obligations to foreign authority. The Rev. Jón Bjarnason represented the Icelandic National Church but Rev. Páll was educated and ordained by a Norwegian Church in the United States that paid his salary, so he was quite involved with a foreign Church. Those in New Iceland who joined his congregations were, in the eyes of the others who followed Rev. Bjarnason, rejecting the Icelandic State Church and thus taking a big step into North American Community. To accept a loan and gifts from Norwegian Farmers, all of whom were members of the Norwegian Synod was unforgiveable in the minds of “Jónsmenn” (followers of Rev. Bjarnason). To them that was not a sign of wanting to be totally independent and unsupported by a foreign body. It needs to be mentioned that the Government of Canada loaned all Icelanders in New Iceland 80 thousand dollars to be paid in full in 1889. It was never paid and the debt written off once it was clear that the majority of people in New Iceland who had settled there during 1875-1880 moved away. J.Th.

Note: All quotations in italics are from Pioneer Icelandic Pastor by George J. Houser. Other matters by Thor Group.